Freepost: General Wrangel asks "What's in a name?"

What kind of White Army are we running here?

This article was once available exclusively to paid subscribers. I’m making it free now because I think it’s particularly relevant to ongoing conversations. If you enjoy this article, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work.

The Russian Civil War (1917-1921) is one of the most understudied conflicts in history, and one of the most important. Following the Russian Revolution that everyone learned about in school, during which liberals first overthrew the conservative Czar, only to themselves be overthrown by radical communists a few months later, were years of fighting between the communists and the scattered groups that opposed them. By the time it was all over, several new nations had been created out of the fallen Russian Empire, along with the Soviet Union, and 12 million people had died.

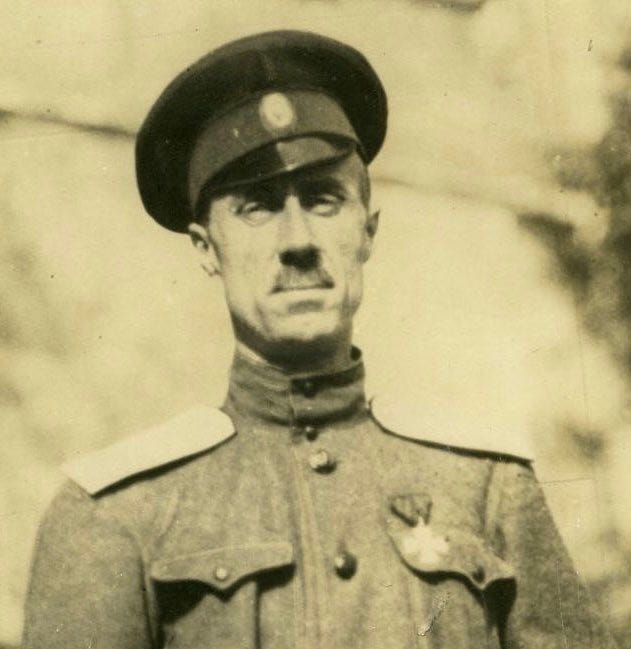

The most respected anti-communist leader during the Russian Civil War was General Pyotr Wrangel. Wrangel was a career army officer who was awarded Russia’s highest medal for bravery during World War I. When the revolution broke out and the liberal government took power, he resigned from the Russian military in protest and left the capital for his family home. After the communists seized control of the government from the liberals, Wrangel was almost executed by one of the many paramilitary units sent out to terrorize the population. Barely escaping death, Wrangel resolved to fight the communists any way he could.

But there was a problem for men like Wrangel. Although Russians generally agreed that the communists had to go, no one could agree on how to do it. The anti-communist forces during the Russian Civil War were collectively called the “White Army.” However, the White Army wasn’t organized like a real army.

When the communists took over, they took over the entire existing Russian government, including the military. They did a very bad job running that government, and many government employees simply left rather than follow their orders, but it was relatively clear who was in charge—they had a pre-existing structure and organization to fall back on.

The anti-communists, on the other hand, had to start from scratch. Their leaders could not agree on who was in charge, or even what they were fighting for. Some wanted a new Czar, others wanted a democratic republic, others, including many Cossacks, Ukrainians, Finns, and Poles, wanted to use the chaos of the Revolution to secure independence from the Russian Empire altogether.

For many former Russian officers, joining one of these non-Russian nationalist groups was the only way they could have a chance to fight the communists as part of an organized military force. Complicating matters even further was that as the Russian Revolution was going on, World War I was still happening. Germany, which had financed the communists to begin with, was advancing deep into the Russian Empire with little in the way to stop it after the Imperial Army disintegrated. Some patriotic officers, even though they hated the communists, volunteered for the communist-controlled Russian military just for the chance to fight the Germans.

After General Wrangel escaped death, he travelled to Kiev, which was then being occupied by the Germany. One of Wrangel’s old friends, Pavlo Skoropadsky, had declared himself the head of a newly independent Ukrainian nation, though this government was supported mostly by German troops with relatively little buy-in even from Ukrainian nationalists.

Skoropadsky offered Wrangel, already known as a brilliant and fair commander, a job as his chief military advisor. Wrangel refused, knowing that once Germany (which was badly losing WWI on the Western Front by that point) inevitably left Ukraine, it would be impossible for a German-backed government to keep the peace.

This is exactly what happened. The Germans withdrew and Ukraine quickly became a battleground for various warring factions. Wrangel left Ukraine for the southern-most tip of Russia, where some of the most elite former soldiers of the Russian military had assembled in a group known as the “Volunteer Army.” The Volunteer Movement was a patriotic society created in the early days of the Russian Revolution to oppose the communists.

Despite many military victories, the Volunteer Army’s disorganization and the general collapse of Russian society created many problems. There was no law and order. The chain of command was unclear. The normal system of food distribution and military supply had broken down. Many soldiers used the chaos as a chance to loot and pillage from the population they were supposed to be protecting. Even though Wrangel distinguished himself as a military genius and one of the few commanders who had zero tolerance for criminal behavior, the reputation of the Volunteer Army among ordinary Russians became very bad.

The Volunteer Army eventually changed names, becoming the “Caucasus Volunteer Army” after its leader, General Denikin, signed an agreement and merged with several Cossack military groups near the Caucasus mountains. Soon afterwards, the force changed names yet again, into the “Armed Forces of South Russia,” as it incorporated even more anti-communist military units into its organization.

Although this became one of the largest groups in the White Army, the Armed Forces of South Russia (AFSR) was mostly united by their shared hatred of the communists. The problems with disorganization and internal division remained. Commanders would undermine each other in the media, refuse to follow orders, and generally fail to cooperate as one would expect members of normal military to do. Making matters worse, General Denikin was an insecure and often irrational military leader who was unable to manage these disagreements.

These different and changing names provided a great deal of rhetorical ammunition to the communists. The communist had seized control of the Russian state mostly intact. They occupied former government offices and appointed replacements for government officials. They claimed that they represented Russia and the Russian people. While both the communist Red and the anticommunist White Armies received substantial foreign aid, and the Bolsheviks had launched their revolution with funding from German military intelligence, the Bolsheviks used their inherited positions claim that the Whites were merely puppets of foreign countries. It was difficult for the Whites to create the appearance that they were the legitimate authorities in Russia as many of their units acted more like medieval warbands than government representatives.

The soldiers of the AFSR fought very bravely but eventually suffered a catastrophic military defeat due to Denikin’s poorly conceived attack on Moscow. As they retreated in disorder, the many factions of the White Army turned on each other again. Their leaders immediately fell back into the divisions and bickering that existed before the fragile alliance. Denikin, always jealous of Wrangel for his popularity and reputation for integrity and competence, had Wrangel exiled from Russia before Denikin himself fled the country. Leaderless and divided, the remnants of the AFSR waited for the end.

But Wrangel couldn’t abandon his country or the men he had fought with. With Denikin gone, Wrangel returned to Russia and was made the head of the White Army on the last strip of Southern Russia still controlled by the anti-communists. With just a small number of loyal troops remaining, he quickly restored order and began reorganizing the scattered and disorganized former AFSR units into an effective combat force, successfully defending their remaining territory from a much larger communist army.

One of Wrangel’s most significant changes had nothing to do with the actual organization of the military, but rather what it was called. On April 28, 1920, General Wrangel issued an order renaming his force to the “Russian Army” and changing the names of the various military units to their pre-Revolution equivalents.

Wrangel’s reasons for this change were simple. He said “...of the two armies fighting in Russia, the right to the name ‘The Russian Army’ belonged to the one composed of men who had remained loyal to the national flag, sacrificing everything for the welfare and honor of their country. Obviously the name ‘Russian Army’ could not be given to troops whose leaders had replaced the Russian tricolor with the Red flag, and the very name of Russia with the name International.”

In doing this, Wrangel had cracked the code that so many of his predecessors had failed to solve. Wrangel was a general in the Russian Army. Nearly everyone fighting for him had been a part of this army as well. While normal people might have a hazy idea of what the “White movement” or the “Volunteer Army,” or even the “Armed Forces of South Russia,” stood for, the Russian military was something that they all knew, understood, and generally liked. The divisions that existed in the past, the petty scheming and factionalism which derailed previous efforts, might have been expected in impromptu political militaries but would have been immediately out of place within a proper army with centuries of tradition behind it.

The new Russian Army under Wrangel faced many challenges in their small sliver of territory: they were greatly outnumbered, had no natural resources, and their international support was dwindling. Despite this, Wrangel launched several missions to rescue former AFSR troops that had been separated during Denikin’s disastrous retreat. He also implemented a series of innovative economic plans, allowing peasants to easily purchase their own small farms on public and abandoned land, that were so popular with normal Russians that the communists ordered the execution of any communist soldier or civilian found carrying flyers describing the reforms. Wrangel’s forces even attempted their own offensive operations. This was a truly miraculous effort on the part of an army that was greatly outnumbered and on the brink of total defeat just a few months ago.

Sadly, victory was just not in the cards for Wrangel’s Russian Army. After several anti-communist breakaway nations signed peace agreements with the communists, Wrangel’s holdouts became the focus of nearly all communist attacks. The odds were just too great, and Wrangel was forced to order the total evacuation of his forces. However, unlike under Denikin, Wrangel’s withdrawal was conducted with the ultimate military discipline. Understanding that defeat was a possibility, Wrangel had quietly prepared a massive fleet to ferry his men to safety.

Consisting of 126 ships, Wrangel’s fleet evacuated roughly 150,000 soldiers and civilians. It was the largest naval operation of the era until the D-Day Landings, and it occurred with no disorder and minimal casualties. Even after the evacuation, Wrangel’s Russian Army stayed together, creating a civilian organization known as the Russian All-Military Union to coordinate the activities of Russian refugees. All of this was possible because Wrangel reoriented everyone’s expectations away from the chaos of his predecessors and towards a firm and established structure and tradition.

General Wrangel’s memoirs, released in English under the title “Always with Honor”, offer a wealth of insight for American conservatives concerned about the state of their country. As American life becomes increasingly unrecognizable and institutions that people once trusted become more and more disgraced, there is an instinct among many conservatives to find a new label for themselves. Some even think they could create new countries out of this dissatisfaction.

These instincts may be understandable, but they have led individuals in similar situations in the past to disaster. However bad conditions may be, conservatives should focus on labels people know and understand. The radicals in charge now, who attack the country’s past and are trying to radically transform it into something new, should never be given exclusive claim to hundreds of years of proud American history and identity.

Subscribed. If you had to choose one book about the Russian Civil War, what book would it be?

Ever think about the possibility of renaming the 'USA' to 'America' for a similar purpose of inspiring ethnic consciousness? (Yes it's impossible but just a thought)