How was the very important Great Depression era Civilian Conservation Corps created?

The Administration of the Civilian Conservation Corps by Charles Price Harper, Chapter 1

In my latest (very good) podcast episode on the development of the US Army before WW2 I mentioned the role that the short-lived Civilian Conservation Corps (1933-1942) played in the nation’s recovery from the Great Depression. If you don’t know, the CCC was an employment program that targeted young men (eventually parallel programs were set up for young women and veterans of WWI) who had been affected by the nation’s economic tailspin and subsequent social breakdown.

Millions of young men were unemployed during the Depression. At its peak, there were more than 250,000 homeless teenagers “riding the rail” looking for seasonal employment or adventure, which caused enormous problems for any area in which they concentrated. These big upheavals aren’t usually reducible to a single event, but rather a series of cascading failures and stressors. One of my favorite books about this period is Charles Willeford’s memoir “I Was Looking for a Street,” which describes the author’s (who later became a WW2 tank commander and renowned weird crime fiction author) childhood as a hobo crisscrossing the country, having run away from home to avoid burdening his family.

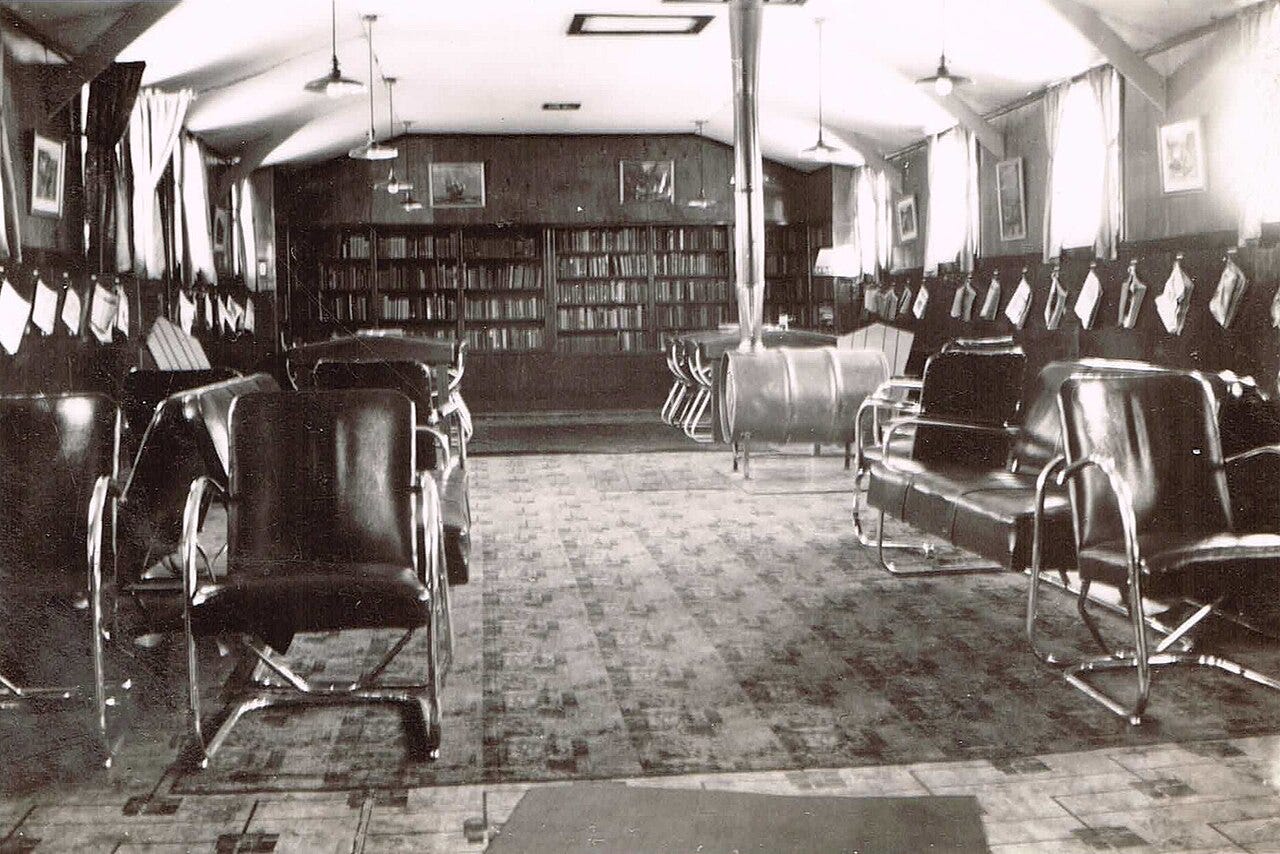

Crime, drug use, prostitution, and other anti-social behavior all skyrocketed. One high-ranking military described the CCC as engaging in a process of “human reconstruction” for those who had become “poor candidates for citizenship.” You had all these young people who had been thrown into hard times by economic forces far beyond their control and reintegrated them back into normal life by giving them respectable jobs, professional training, decent wages (CCC enrollees were paid more than Army privates, which caused considerable controversy), free room and board, and ultimately a sense of responsibility for society.

One of the things I’ve complained most about is that conservatives today don’t really have a good sense of how things work: How ideas form, how they become realized in systems, and how those systems change the world. It seems like the modern Right is constantly stuck in the “idea” phase. Whenever they approach the “systems” phase, suddenly a lot of people are out of their depth and become very anxious to get back to the drawing board for this pretext or another. Unfortunately for us, since Trump won and we are nominally in control of the government, we are not going to be able to improve our situation with a new debate club.

I think the CCC was a good program, and one that I think could be used (if updated properly) to great effect today. To that end, I’d like to reproduce a 1937 PhD thesis on how the Civilian Conservation Corps was actually run. There’s quite a bit of coverage of the CCC, it was one of the most popular government programs during the Depression Era, but the actual mechanics of the organization are usually left unexamined.

What follows below is one of the few thorough surveys of the program: The Administration of the Civilian Conservation Corps by Charles Price Harper. Although the work was originally submitted as Harper’s PhD thesis at Johns Hopkins University, it was later published in book form in 1939. One of my beloved subscribers (paid) was nice enough to check this out from a rare books library (it’s not available even on online sources like archive.org) and scan it for me. I haven’t recreated the footnotes, which would have taken an enormous amount of time and only been of interest to a few readers, though I left the numbers in just to illustrate that this was a very lovingly researched book. You should view historical pieces without this detail (including my own) very skeptically!

I find this stuff really interesting. It’s my hope that this will encourage renewed interest in the CCC or at least make this very rare text available online in some form. Always remember that it’s not enough to just “have the idea.” There is a surplus of good ideas right now and an extreme shortage of the skills, personnel, and (perhaps most importantly) will to bring them into being. This is our challenge going forward.

Most recent podcast episodes:

Ep74: The Mega WW2 episode (Paid)

Ep73: I hated normieslop F1 the Movie (2025) in a way I didn’t think possible (Paid)

Ep69: Zen police ultraviolence simulator Ready or Not (2023) is the only game for our time (Paid)

Ep68: “Days of Rage” is the most important book for you to read today, right now (Paid)

[Begin selection]

CHAPTER I

HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE EMERGENCY CONSERVATION WORK PROGRAM

The first of the numerous projects initiated by the New Deal was the Emergency Conservation Work program. The purpose of this program is threefold: the relief of acute distress caused by unemployment, the building of health and morale among thousands of young men, and the restoration of the depleted resources of the United States. This emergency conservation project is being carried on by the Civilian Conservation Corps and a few similar agencies. They are engaged in the protection and improvement of forests, parks, watersheds and other natural resources. The work is under the supervision of the Emergency Conservation Work organization, the departments of Agriculture, the Interior, Labor and War, and several bureaus of service. Some knowledge of the origin and development of the Civilian Conservation Corps and its allied agencies is essential to the understanding of their organization, functions and administration.

Development of the Idea.

Secretary of War, Dern, ·has rightly called President Roosevelt the °”: “father of the Civilian Conservation Corps” because the idea was solely and wholly the President’s.1 One cannot be certain how long the idea was in the mind of the President, but his interest in conservation dates from his boyhood. His mother has stated that, while yet in his “teens,” he was interested in forest conservation on their Hyde Park estate.2

Like Washington at Mt. Vernon, Roosevelt recognized that every’ homestead, like each member of a family, should have its own individuality and saw that this could be developed by forest conservation. Professor Raymond Moley, former Assistant Secretary of State, thinks the President got the idea at Harvard, when he heard William James discuss the moral equivalent of war. In his essay on this subject James said in part:

If now . . . there were, instead of military conscription, a conscription of the whole youthful population to form for a certain number of years a part of the army enlisted against Nature, the injustice would tend to be evened out, and numerous other goods to the commonwealth would follow. . . . To coal and iron mines, to freight trains, to fishing fleets in December, to dishwashing, to road building and tunnel making, to foundries and stoke holes, and to the frames of. skyscrapers would our gilded youths be drafted off, according to their choice, to get the childishness knocked out of them, and to come back into society with healthier sympathies and soberer ideas.

While, in his own words, “a youngster in the State Legislature,” Roosevelt, “for no known reason,” was made chairman of the committee on forests, fish and game. He thought this position was given him because nobody else wanted it, but he soon took deep interest, in his assignment, though he knew very little about it. He invited Gifford Pinchot, the Chief Forester of the United States, to Albany to advise him and the Legislature, and Mr. Pinchot, whom the President has called one of the first of the “brain trusters,” delivered a professional lecture on the subject of conservation. In speaking of this lecture and the work of his committee, the President said: “We passed our legislation and that was the first step toward practical government supervised forestry as far as I know in the eastern part of the country. It started me on the conservation road.”5

Through his long practice of forestry as a private citizen and his interest in conservation as Governor of New York, the President has rightly been called “forestry minded.” His conservation work on the twelve hundred acre Hyde Park estate, especially since 1915, is comparable on a miniature scale with what he is attempting to do in the national forests. Over five hundred acres are given over to forests, and worn-out land is reforested. Besides reforesting with many different species, the conservation work includes the cutting and selling of mature timber, and the protection of the land along the Hudson against soil erosion.

The President is familiar with even the details of his carefully tended and constantly improved five hundred acre forest tract. He has reserved over one hundred acres for ecological, esthetic and experimental purposes, and the remainder is devoted to timber producing areas, divided into seven working groups, each managed somewhat differently. A new phase of reforestation was introduced when he demonstrated the practicability of growing Christmas trees commercially.8 Perhaps this experimentation in reforestation and conservation influenced the President’s idea of using the experimental method in government.

Mr. Roosevelt’s reforestation work was not confined to his northern estate. During Southern vacations he acquired sundry abandoned farms in the South, reforested them, and then organized local protective associations to further the cause of conservation. Speaking on one occasion of conservation he said: “There must be replacement and a policy of administration that will guarantee a maximum of beneficial use with a minimum of waste. Our forests and waters and the wild life that they support are essential to the health and economic welfare of the people.”10

As Governor of New York, Mr. Roosevelt undertook a program of reforestation in a broad way. He tackled the subject as though nothing else of any importance had been suggested by his administration and the program initiated by him soon caught the imagination of the entire country.11 a very definite program was worked out with regard to submarginal land and its possible use for “the growing of crops of trees.”12 A law was passed “providing for the purchase and reforestation of these lands in a manner approved by the State, part of the cost being borne by the county and part by the State.13 In 1931 the people voted the “Reforestation Amendment,” which called for large scale reforestation of marginal land then put to no productive use. This amendment has a definite schedule providing for the appropriation of twenty million dollars to be expended over an eleven year period in the purchase and reforestation of over one million acres of land. This schedule of appropriations for the purchase, planting and conservation of abandoned, idle and useless farming land was suggested by Roosevelt to guide future legislatures in their reforestation legislation.14 Reforestation has also made its contribution to the relief of unemployment in the State. During the last year of Mr. Roosevelt’s governorship, ten thousand extra persons from community unemployed lists were used in the tree nurseries and for the planting crews.15 It was this, no doubt, which suggested the wider use of the unemployed on reforestation projects in the nation.

With President Roosevelt’s New York experience in reforestation in mind, one can readily appreciate the significance of that part of his speech of acceptance which many thought fantastic, but in which he said:

We know that a very hopeful and immediate means of relief, both for the unemployed and for agriculture will come from a wider plan of the converting of many millions of acres of marginal and unused land into timberland through reforestation. There are tens of millions of acres east of the Mississippi River alone in abandoned farms, in cut over land, now growing up in worthless brush. Why, every European nation has a definite land policy, and has had one for generations. We have none. Having none,’ we face a future of soil erosion and timber famine. It is clear that economic foresight and immediate employment march hand in hand, in the call for the reforestation of these vast areas.

In so doing, employment can be given to a million men.17 That is the kind of public work that is self-sustaining, and therefore capable of being financed by the issuance of bonds which are made secure by the fact that, the growth of tremendous crops will provide adequate security for the investment.

Yes, I have a very definite program for providing employment by that means. I have done it, and am doing it today in the State of New York. I know that the Democratic Party can do it successfully in the nation. That will put men to work, that is an example of the action we are going to have.18

The public proposal of such a far reaching conservation and unemployment program evoked derision from friend and foe alike. The candidate’s friends explained the suggestion as one of his “brain storms,” and his opponents spoke of it with ridicule. Secretary of Agriculture, Arthur M. Hyde, whose department had charge of the Forest Service, interpreting reforestation in the narrow sense, explained that only a few thousand men could be put to work planting trees. He spoke of the proposal as being of an “utterly visionary and chimerical character.”19

But the Roosevelt proposal was not a mere campaign promise, to be forgotten with the passing of the summer heat. It was an essential part of an emergency program for the immediate relief of that increasing army of unemployed which was looking to him for relief. It was to be the first experiment of the New Deal. If there was any doubt as to the purpose and scope of the candidate’s proposal, it was cleared away as the campaign progressed. At Atlanta, in speaking of why he believed just as much in country planning as in city planning, Mr. Roosevelt said:

Everyone knows that we are using up our American timber supply much faster than the annual growth of new timber. Therefore, unless we are willing to face a day not so far distant when we shall become a nation dependent on importing the greater part of our lumber from other nations, we must take immediate steps greatly to increase our home supply.

It is common sense and not fantasy to invest our money in tree crops, just as much as to grow annual agricultural crops. The return on the investment ^ just as certain in the case of growing trees as it is in the case of growing cotton, or wheat, or corn. ...

Because we are a young nation, because apparently limitless forests have stood at our door, we have declined up to now to think of the future. Other nations whose primeval forests were cut off a thousand years ago, have been growing tree crops for many hundred years.20

At Boston, a few days later, he stressed the relief feature of his reforestation program when he said, in part:

The first principle is that the nation owes a positive duty that no one shall be permitted to starve. Second, in addition to providing emergency relief, the Federal Government should provide temporary work wherever possible. In the national forests, on flood prevention and on the development of waterway projects already authorized and planned, thousands at least can be given temporary employment.21

These campaign statements, coupled with his conservation program as Governor of New York, gave the American electorate a clear-cut idea of the definite emergency relief and conservation program of the new President. As unemployment grew worse and the economic situation more tense during the winter months, everyone was wondering what the new leader’s first line of action would be, and when it would begin. When Roosevelt was inaugurated there was no time to speculate upon the causes of unemployment. “It was a fact. It was contributing to an unprecedented increase of crime. It was the principal factor behind the increasing appearances of social unrest indicating a serious threat to the social structure, even as licks of flame in a smoky building portend a condition menacing the very existence of the edifice.”22 In his inaugural address the new President said:

Restoration calls, however, not for change in ethics alone. This nation asks for action, and action now. Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously. It can be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war, but at the same time, through this employment, accomplishing greatly needed projects to stimulate and reorganize the use of our natural resources.23

In that paragraph one can visualize the Civilian Conservation Corps as the “vanguard” of “The New Spirit of American Future,” as the President called it in his first radio address to the “forestry army.”24

Proposal of the Program

Although the banking crisis of “the first twelve days” may have delayed President Roosevelt’s breaking away from the old order and the beginning of his “new order,” yet it was evident that he would lose little time in launching his emergency conservation work program. On the very day Congress met in extraordinary session, the secretaries of Agriculture, the Interior, and War, the Director of the Budget, the Judge Advocate General of the Army, and the Solicitor of the Department of the Interior met with the President to hear him outline his program for the conservation of men and forests. His hearers agreed that the idea was good, that it could be set in motion immediately, and that there was need for such labor in the forests. The Judge Advocate General, Colonel Rucker, assured the President that he could put the program into necessary and legal form for presentation to Congress by nine o’clock that night. At that hour the group reassembled, discussed the plan, expressed their views, and made several changes; and at ten-thirty the President placed “this new child of government” before a delegation of congressional leaders who awaited him.25

The original bill, introduced in Congress March 13, by Senator Costigan,26 evoked much criticism.27 It was redrafted in more general terms and passed upon by the President at a White House conference two days later. He informed the congressional leaders that he desired to have his unemployment relief measure enacted before the proposed two or three weeks recess was taken, and to have it financed by unexpended balances in the Treasury and not by bond issue. He also expressed his desire to have the conservation workers placed on reforestation projects in the national preserves near the large centers of population. The Forestry Service estimated that $150,000,000 could be wisely expended in the national forests annually.28

It was evident from the President’s message to Congress on the “Relief of Unemployment” that the Civilian Conservation Corps was to be the first immediate step to meet the unprecedented conditions brought about by the depression. In this message he said:

It is essential to our recovery program that measures immediately be enacted aimed at unemployment relief. A direct attack on this problem suggests three types of legislation.

The first is the enrollment of workers now by the Federal Government for such public employment as can be quickly started and will not interfere with the demand for or the proper standards of normal employment.29

After explaining the second and third types of relief, namely, the grants to States for relief work, and the extension of “a broad public works labor-creating program,” the President continued:

The first of these measures which I have enumerated, however, can and should be immediately enacted. I purpose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control and similar projects.30

He then called attention to the definite and practical value of such work as a means of creating future national wealth as well as “through the prevention of great personal financial loss,” stating that the work could be carried on by existing governmental machinery. He continued: “I estimate that 250,000 31 men can be given temporary employment by early summer if you will give me authority to proceed within the next two weeks.”32

Next to the call for quick action was the unusual statement that he would ask for no new funds at that time, but would use unobligated funds, appropriated for public works.33 The statement that “this enterprise is an established part of our national policy”34 referred to the conservation of “previous natural resources,” rather than to the permanency of the enterprise. Yet such a broad statement of policy leaves room for speculation as to the permanency of this or a similar program for the unemployed youth of the nation. One of the aims, and to the President the most important, was stated in his message as follows:

More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work. The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans, who are now walking the streets and receiving private or public relief, would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings. We can eliminate to some extent at least the threat that enforced idleness brings to spiritual and moral stability. It is not a panacea for all the unemployment, but it is an essential step in this emergency.35

Immediately after the reading of the President’s message on March 21, a bill coming down from him and prepared under his direction,36 to carry out the principles of relief and conservation as given in the message, was introduced jointly in the Senate by Senators Robinson, of Arkansas, and Wagner of New York, and was referred to the Committee on Education and Labor.37 An identical bill was introduced simultaneously in the House of Representatives by majority leader Byrnes, of Tennessee, and was referred to the Committee on Labor.38 The bill, in its brevity, a characteristic of legislative proposals of the Administration, omitted many of the stipulations evolved during the study of the plan by Secretary Perkins and Senators Wagner, Costigan, and LaFollette.39

Fearing that the Administration bill might be changed in Committee unless those dealing with it had more definite ideas as to its purpose, scope and effects, a conference was held with the President, at the request of Senator Walsh, presiding chairman of the Joint Hearings of the Senate and House committees on the measure.40 This conference, held the night before the Joint Committee hearings began, included the Committee members and Secretaries Perkins, Dern, Ickes, and Wallace. Suggestions were made as to the rate of pay, use of unobligated public works funds for financing, placing the Army in charge of mobilization and operation of the camps, and enlarging the scope of the work to include the wiping out of the gypsy moth.41

Public Reaction to the Bill

Before the hearings of the Joint Committee of the Senate and the House had proceeded far, it was evident that the proposed bill would be radically changed. Opposition to its provisions as written came from friend and foe of the whole emergency relief program. As soon as the bill was presented Labor voiced its opposition through the President of the American Federation of Labor. President Green’s chief concern was the military feature of the plan. He thought it would mean the “regimentation of labor” with a form of compulsory service under military control and army rates of wages. Such a plan, he feared, would awaken feelings of “grave apprehension in the hearts and minds of labor.”42 A. F. Whitney, President of the Brotherhood of Trainmen, in a letter to Donald Richberg, termed the program inadequate, vicious and weak. He said that it “would place government’s endorsement upon poverty at a bare subsistence level.”43 It was evident from these and other criticisms that the critics had not followed the President in his development of the idea, and had formed hasty and unwarranted conclusions in regard to some of the proposals.

The late Major R. Y. Stuart, Chief of the United States Forest Service was the first witness to give his views to the Committee. He stated that there are 161,000,000 acres of national forest lands, the great hulk being in the Far West, and only 7,000,000 acres of national forest lands and some 15,000,000 acres of state owned and controlled lands lying east of the Mississippi River. He proposed an amendment to extend the scope of the work to private lands adjoining or near any public domain, because tree pests and fire hazards on such lands are unusually detrimental to the public forests. Only fifty-four per cent of the forest lands in the United States, he said, were under forest protection, and there was already in operation, although inadequately financed, a cooperative arrangement between the Federal Government and the various States in conservation work.44 To this proposal Senator Walsh replied that the White House conferees had felt that such a plan might involve competition with private labor, a consequence which the Administration wished to avoid.45

Major Stuart then spoke of the relief feature of the proposed bill and compared it with the cooperative arrangements which the Forest Service had made with some of the States and counties.46 in California the Service had operated some subsistence camps, the State or county furnishing the money to feed and clothe the men, and the Forest Service furnishing them shelter in the woods for the preservation of which they were working. The stipened paid in the camps both of California and of some of the Lake States was not really considered compensation, as the men would receive it anyway under the relief provisions. According to Mr. Stuart, both the workers and those in charge of these subsistence camp programs felt that it was more helpful to furnish the men with something to do rather than to have them receive this relief in idleness 37

The Chief Forester suggested further that the mobilization and conditioning of the men could be more expeditiously and economically carried on by the Army, as the Forest Service had no facilities, especially in the East, for such service.48 This suggestion brought up the question of where the men from the East would be sent, some members of the Committee fearing that the men would be sent from their home states to some distant section.49 This query was answered by showing the possibilities of employment in the East on state forests, although approximately ninety-five per cent of the public domain, the national parks and forests, lies between the Rocky Mountain region and the Pacific Coast. Major Stuart stated that, if the bill were confined to work in the national forests alone, many would have to be transported to the West, and he would not advise this.50 He wished rather to see the bill broadened to include privately owned lands where a public benefit is to be served in line with the policy followed in forest protection.51

In conclusion Major Stuart pointed out the possibilities of work in the national parks, the public domain, and other Federal and State owned property which would come within the plan. He showed the need for conservation work in the national forests, and stated that only $9,000,000 had been allowed for the 1933 improvement work, and $5,000,000 for that of 1934. He said that for the previous twelve months the Forest Service had had approximately 2,700 men in its employment, and that it had been necessary for them to move along at a very slow pace in their protective and administrative work. This statement brought up the question of trained supervisors for the proposed conservation corps, and the witness said that his Service had a considerable number of foresters, woodsmen, and others, skilled in the work, who could be used. Finally, he indicated to the Congressmen that those men already employed in the national forests would not be displaced as a result of the proposed plan.52

Secretary of Labor, Perkins, in her first appearance before a congressional committee, defended the proposed plan as a relief measure, saying: “The purpose of this legislation is to provide a practical form of work relief for about 200,000 or 250,000 men, aiming to give a form of \ work relief which can be accepted by self respecting citizens without any impairment of their personal dignity.”53

The Secretary stated that there was a large group of unemployed men who had experienced great difficulty in securing adequate relief or in being able to shift for themselves. These young and unmarried men had been left out of the aid of most relief agencies, because it had been felt that those with families should be taken care of first. Many of these people “who have been picking up a bit here and a bit there,” had been forced “to a standard of living and type of behavior which they as good, sound Americans could not and did not endorse.” It was from this group that most of the Civilian Conservation Corps would be recruited.54

When one of the Committee members intimated that the program was a “sweatshop” project, Secretary Perkins said: “I do not think any one should regard this project as in any way approaching that kind of work.” Her reasons were: that the men would be those dependent upon relief and unemployed; that they would be covered by the Workmen’s Compensation Act; that all necessary transportation would be furnished; that the men would get $30.00 per month whether they worked or not, which was not true of either skilled or unskilled laborers; that it was inconceivable that these men would work eight hours per day; and that recreational and educational activities would be carried on for their benefit.55 The Secretary was then asked what she thought would be the effect upon private industry of a bill providing for a wage of a dollar a day, and if she did not think that every private industry would immediately say that it should be the prevailing rate throughout the United States. She replied tersely: “I do not think so, sir, because it does not make sense. ... I think that ordinary self-protection would lead industrialists to recognize the need of paying a wage which will produce more purchasing power.”56

Secretary Perkins thought it would be foolish to limit the plan to unmarried men, as the enrollment would be voluntary. She did not think the effect of the husband’s absence on the family life would be very marked, as “family life in America on the whole is very sound.” Instead she feared more danger from the unemployed man’s becoming detached from his family by desertion, since he has to make his rounds to the relief agencies for his basket. Finally, she defended the physical examination of the enrollees on the ground that crippled or disabled men and those with heart disease could not endure the hardship. She did not think that the knowledge that a person was defective would make it impossible for him to get a job elsewhere, since certain kinds of defects might prevent him from doing forestry work, yet would not be a handicap in other occupations.57

There was serious objection in the Committee to that part of the bill which authorized the expenditure of such unobligated moneys in the Treasury, heretofore appropriated for public works, as might be necessary and available to finance the program.58 Consequently, Director of the Budget Douglas, was called the second day of the hearings, and devoted most of his time to answering queries regarding this provision. The answer to the finance question, the Director said, had to do with the immediate future and with the next year or thereafter. The use of remaining unobligated public works funds for immediate financing was more advisable than asking Congress for an additional appropriation. In the meantime the Administration was working on the method by which coordinated relief and unemployment program could be financed. Mr. Douglas estimated the cost of the Emergency Conservation Work program at $250,000,000 for the first year, or about $20,000,-000 per month. He assured the apprehensive Congressmen that it was contemplated to carry into the completed and coordinated unemployment and relief program public buildings and other public works projects, although the obligation of funds for such authorized and new projects was temporarily suspended.59

Another major public criticism centered around the Army’s part in the conservation program, and General Douglas McArthur, Chief of Staff, was called to present its views. He said in part:

The history of the uniformed service will show it [the Army] has not only the war-time mission of protection of law and order, but that it is a great emergency relief organization. It is upon that general basis and background that the Army, as I understand it, is to be utilized in the furtherance of the plan. . . . The various agencies scattered throughout the country will select those individuals who are to be enrolled. The Army will then collect these men in the various centers for the purpose of rehabilitation, for the purpose of fitting them with shelter, food, clothing, equipment, preparatory to being checked out to the various labor projects. The time . . . involved . . . will probably be not more than a month.60

Later he estimated that the cost of processing these men for a month would be about $35.00 each, including the necessary expenditure for their shelter, food, equipment and for the implements they would use in the forests, but not transportation or any cash allowance they might receive.61

When asked about physical or military training for the men, the General replied: “No military training whatsoever,” and the only physical training would be “that which any well ordered community would go through in order to keep men in physical condition, so they will be prepared physically for the tasks which they are to undergo.” The General, when asked if the bill was not similar to the original selective draft act of the World War, said: “As far as the Army is concerned, it is not similar.”62 Senator Black came to the defense of this phase of the bill, stating that he did “not think it would be possible to draw a constitutional bill in peace time where men would be conscripted for peace service.’’63 General McArthur clarified the controversial question of discipline to which the enrollees would be subjected when he said, “when we have them, there will be such ordinary and decent requirements as any civilized community would have.”64

Perhaps the most opposition to the bill came from President Green of the American Federation of Labor, who publicly criticized it as soon as it was offered in Congress. Before setting forth Labor’s feelings in regard to it he expressed, first, his desire to approach the discussion, “in the broadest possible spirit,” and secondly, his appreciation of the sincere and humane consideration of its sponsors, who had “a desire to do something to relieve unemployment.” He continued that he was in thorough accord with the aim of the bill, and the need to find employment for idle persons, where they can earn a decent living, saying: “But I do not believe . . . that it is necessary to regiment labor, to enlist it in an army, to place it under at least a form of military control, of military domination, in order to accomplish that purpose.” Commenting upon the Army’s part in the proposed plan, as given by General McArthur, Mr. Green said: ‘‘This is military control in itself. There is your regimentation, the very principles against which labor has always vigorously contended. It smacks as I see it, of fascism, of Hitlerism, of a form of sovietism.”65

Mr. Green’s second objection to the bill, which he considered as important as that of regimentation^ was in regard to the rate of pay.67 He contended that the bill was not a relief measure in the full and complete sense of the term, because it set the amount of compensation that was to be paid for a day’s work.” 68 Later he pointed out that the relief feature was in the hospitalization, the food, the shelter, and the one dollar per day provisions.69 The compensation rate, however, he feared, would be accepted as a standard rate of wages, and labor was opposed to such compensation, “not only because of the wage itself, but because of the depressing effect upon the wage standards established by labor in private industry.”70 Previously he had made it clear that he was not opposed to the reforestation project but to the rate of pay and the method proposed.71

Other objections voiced by the labor leader were: the use of unobligated funds, if it would delay public works construction, and the involuntary allotment of part of the enrollee’s pay to his dependents.72 Yet unlike most critics, Mr. Green gave the Committee his own idea of such a program. His recommendation was as follows:

That a plan of employment of idle workers in reforestation and reclamation and other items covered by the bill be formulated providing for the payment of standard rates of pay under voluntary conditions of employment and that the element of ‘forced labor* and military service be completely eliminated and stricken from the plan of employment to be followed.73

Other witnesses against the measure claimed that it discriminated against the negro;74 that it was a camouflaged relief measurer;75 that it provided for the establishment of “forced labor,” starvation wages and “the destruction of the families of American workers.”76 One witness even went so far as to object to placing men in camps other than those of their own selection. He contended that they would be forced to stay in the camps, and pay for them with their labor until discharged.77 The hearing closed with Senator Walsh’s reading a letter from a Philadelphian, who voiced his objection to the project by saying that “this plan for putting gangs of helots to work in the national forests is objectionable in many ways . . . it . . . will mean the wholesale ruination of the beauty of the forests.”78 After protesting against “the artificializing of what natural beauty this country still has,” the writer ended his plea by saying: “It is very sad when the juggernaut of bureaucracy is allowed to stamp it [the beauty of the forests] out, as will be done systematically and ruthlessly in the event that this ‘unemployment relief bill’ is passed.”79

Further criticism of the proposed conservation measure came from the Joint Committee on Unemployment, of which Dr. John Dewey was Chairman. In a letter sent to President Roosevelt, while the bill was still in Committee, Dr. Dewey’s Committee objected to associating the Army in any way with the project; the one dollar per day rate of pay; and the type of work proposed.80 in place of the proposal, the Committee recommended a $5,000,000,000 slum clearance program, with the workers paid adequate wages.81 The newspapers were, on the whole sympathetic to the proposal, as they were to most of the other New Deal projects. The New York Times, in an editorial crediting the President with the plan and praising his sincerity and enthusiasm for it, doubted if it would receive the zealous approval of Congresses President Charles Lathrop Pack, of the American Tree Association, voiced the views of his association in a letter to President Green, of the American Federation of Labor. He said that he was astonished at opposition to a relief measure that would pay “a good American dollar” to thousands of jobless.83 Dr. Charles Herty, a New York and Georgia scientist, hailed the program as one in which the President would find the machinery ready for the development of a reforestation program in the eleven Southern Pine Belt states. In these states there were 181,500,000 acres of cut over lands and forests on which one million men could be set to work at once cleaning underbrush, plowing fire strips and resetting pine seedlings.84

Congressional Reaction to the Bill

The many suggestions and objections to the Administration’s unemployment reforestation bill, brought out in the Joint Committee Hearings and expressed by the public at large, showed that it would have to be radically changed to meet public approval. In order to expedite their reports the Senate Committee was called to meet in executive session the next day after the hearings, and the House Committee two days later.85 Both Committees reported the bill favorably to their respective chambers on the latter date, the Senate report constituting an amendment in the nature of a substitute bill.86 Chairman Walsh, when asked whether or not any written report on the measure had been submitted, replied that he did not think one necessary, since the bill itself was so simple and direct.87

In presenting the substitute bill to the Senate, Senator Walsh stated that the Committee, having heard commendation and objections, had agreed that the non-controversial features of the plan were “the opportunity to engage in forestation work as a means of relieving unemployment, and secondly, the use of unobligated funds.” He continued that the substitute bill did nothing more than authorize the President to employ citizens from the ranks of the unemployed to go into the public domain and carry on reforestation. This was to be done under such rules and regulations as the President might prescribe, without restriction, except that the employment be given to unemployed citizens. The Senator called attention to the fact that the bill, like most emergency legislation, gave the President permissive blanket authority.88 The Committee agreed unanimously that this was the only proper way to deal with the problem, because Congress could not well work out the details arising with regard to transportation, conditions of employment, wage schedules, and the location of camps and hospitals.89

Senator Walsh asked the Senators, in considering the bill, to keep in mind three things, namely: emergency, relief work and unemployment.90 In concluding his presentation he pointed out that the substitute bill was illustrative of the temporary emergency policy; that it would enable the President, who was of necessity given wide discretion both as to policy and administration, to act decisively, helpfully and speedily with unemployment relief; that the extent of the benefits of the project could not be estimated; that it should be an important aid in stimulating the resumption of trade and production; and that the Committee felt the President should be left free to determine how to handle the many difficult details in the light of circumstances as they might develop.91

The two days discussion of the Committee bill brought forth practically the same objections and suggestions as those given in the hearings. Judging from the discussion and amendments proposed and adopted, the main objection was the blanket authority given the President.92 Yet Senator Borah, in speaking of granting this extraordinary power, said:

This is the mildest form of delegation of power I have seen in the Senate since this session of Congress opened. I do not think there is anything in the pending bill that is unconstitutional. It may be that there is a question of policy involved, but we have been for a long time granting lump sums and telling the President to do so and so according to his judgment, and if I construe this bill correctly, that is what it does.93

Most of the dozen amendments proposed and adopted by the Senate were of a clarifying or permissive nature.94 Those limiting the authority or discretion of the President were as follows: (a) By Senator Walcott, extending the work to “lands in private ownership,” but only for the purpose of controlling forest fires and disease.95 it will be remembered that such an amen6ment was suggested in the Committee Hearings by Chief Forester Stuart.9G (b) By Senator Couzens, limiting the purchase of private lands to those which were contiguous to the property already in the ownership of the federal government.97 There was perhaps more objection to this amendment than to any other proposed, especially from states which had no federal lands. Senator Connally, for example, feared that Texas would not get the benefits it was entitled to under the proposed relief measure since it had no federal lands.98 (c) By Senator Hebert, limiting the Act to two years. This amendment was agreed to without debate. The Senator desired that the limit be one year, but at the suggestion of Senator Walsh it was made two years.99

The House Committee on Labor accepted the Senate Committee’s bill and filed majority and minority reports.100 The former consisted of the President’s message asking for the bill; statements as to why the substitute bill was reported; and a letter from the President of the American Federation of Labor, expressing his approval of the substitute measure. It stated, furthermore, that President Roosevelt had given his approval of the reported bill and that it was entirely satisfactory. Chairman Connery gave three reasons why the minority could not recommend the adoption of the relief bill. They were: “That these workers will be regimented and physically examined; that under the guise of utilizing unskilled . . . labor, the cash allowance will not exceed $1 per day; that the American public will know that . . . Congress . . . fully realized that these men would be regimented in some manner and that they were to receive for their labor not more than $1 per day.”101

The minority report likewise quoted objections to the original bill as brought out in the hearings, especially in connection with the testimonies of Director Douglas, General McArthur and President Green. Finally, the report gave the Connery amendment to the bill providing for no regimentation of labor; voluntary enrollment for periods of two months; cash allowances of $80.00 for married men or those with dependents and $50.00 per month for single men; the work to be strictly reforestation; and the continuance of all public works authorized and appropriated for.102

Since Chairman Connery was against the reported bill Mr. Ramspeck, of the Committee, presented the amended Senate bill, which had passed that body the day before.103 The House resolved itself into the Committee of the Whole, House on the State of the Union, and majority leader Byrnes, author of the original House Bill 3905, led the argument for the defense.104 The arguments for and against the measure were similar to those given in the Hearings and in the Senate debate as noted above.105 Only three106 of the eighteen107 amendments proposed in the House were adopted. One by Mr. DePriest prevented discrimination against the Negro.108 This amendment, as noted elsewhere, was proposed in the Committee hearings,109 but was not included in the substitute bill. Representative Blanton, of Texas, objected to the DePriest amendment on the ground that it was out of order. The chair overruled the objection and the amendment was agreed to by a vote of one hundred and seventy-nine to seventy-one.110 The second amendment was offered by Mr. Byrnes111 at the request of the President. It changed the wording regarding the purchase, donation, etc., of real property in section two of the Senate bill. The third amendment proposed by Mr. Ramspeck112 merely restored section four, which had been thrown out on a point of order.

After the Committee of the Whole House had risen and reported the bill back to the House with the three amendments, and these had been agreed to, Mr. Connery made a motion to recommit the bill to the Committee on Labor with instructions to report it back to the House with his bill inserted after the enacting clause as an amendment.113 His motion was rejected and the amended Senate substitute bill was passed with the yeas and nays refused.114

The next day the Senate accepted the House amendments, 115 and after the House had authorized the Speaker to sign the bill notwithstanding the adjournment or recess of that body116 it was signed by Speaker Rainey and Vice President Garner117 and presented to President Roosevelt the following day.118 The President signed his emergency conservation work measure immediately in the presence of Senator Walsh and Representative Ramspeck, who had piloted it through Congress, and representatives of the American Forestry Association. In signing, he said: “This law will not only relieve unemployment but will also promote a needed activity in this country.”119

Summary of the Statute

An analysis of the Emergency Conservation Work statute shows that the whole theory of the plan is, as so ably expressed by Senator Walsh, “that we need speed, we need some one with direct authority to act quickly, and we need some one who will try to apply the authority delegated in a helpful way in reducing unemployment.”120 in spite of the sundry amendments added by Congress the statute is more of a permissive act than the original draft. It is based on the principle that the great public domain of the nation provides vast opportunities for employment. The President is given blanket authority to go into that domain and use it at his discretion to partially relieve the unemployment situation, and thereby improve the economic and social conditions of the nation.

Section one of the statute clearly states its purpose: to relieve unemployment, provide for the restoration of the nation’s depleted natural resources, and to advance an orderly program of public works. In order to do this the President is authorized, “under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe,” to provide for employing unemployed citizens, regardless of “race, color or creed,” in the carrying on of work of a public nature in connection with forestation on national and state lands “suitable for timber production;” prevention of forest fires, floods and soil erosion; plant pests and disease control; the construction, maintenance, or repair of paths, trails and fire lanes, in the national forests and park; and such other work on the public domain and Government reservations as the President deems desirable. He may, in his discretion, extend the provisions of the statute to lands of counties, municipalities, and private owners, but only for the purpose of preventing and controlling of floods, forest fires, and tree diseases and pests. The President is further authorized to provide subsistence, clothing, housing, medical care, hospitalization, and cash allowances for the enrollees. He may also provide them with transportation to and from the place of enrollment121 The Forest Products Laboratory is aided in its investigations and research by the allocation of funds from the Emergency Conservation Work program.122

Section two of the statute authorized the President to enter into such agreements with the states as may be necessary for utilizing existing state administrative agencies to carry out the provisions of the act. He may acquire real property by condemnation, donation, purchase, or otherwise, without the consent of the states so concerned. Section three merely makes the Federal employees’ compensation laws applicable to the enrollees. Section four gives authority to use unobligated moneys from appropriations already made for public works (except for projects already or about to be constructed, or already allocated), to carry on the work. Section five is a “rider” to the Committee bill and applies to an Act approved July 21, 1932, entitled “An Act to relieve destitution,” and so forth, and does not concern the emergency conservation work project. Section six, as mentioned before, is the amendment of Senator Hebert limiting the Act to two years from date of passage and no longer.123

A comparison of the enacted emergency conservation work measure with the original bill shows that it gives broader discretionary power and is more in line with the trend of emergency legislation. The original bill restricted the selection of the men “as nearly as possible in proportion to the unemployment existing in the several states,” limited the enrollment to one year, set the rate of pay “not to exceed $30.00 per month,” and provided for the giving of an involuntary allotment to the enrollees’ dependents.124 On the other hand the statute placed no restrictions upon the President except that the employment must be given to unemployed citizens regardless of race, creed or color. The statute also leaves out such other controversial questions as limiting the work to single men; fixing of wages of technical workers according to locality; the kind of camps and form of discipline; and the matter of pensions. Instead, it gives the President the responsibility in the making of regulations concerning the conditions of employment, the selection of the enrollees; the public domain upon which they will work, and the nature and character of the work to be done.125

Organization of the Program

The emergency conservation work statute clothed the President with blanket authority to arrange for the establishment of a nation-wide chain of forest camps, its immediate objective being the relief of distress among the jobless and their dependents; the accomplishment of useful worthwhile work in the public forests, parks and reservations; the rehabilitation of men whose health and morale had reached a low ebb during the depression; and the reduction of overtaxed relief agencies through the allotment of part of the cash allowances of the men to their dependents. Contrary to previous legislation which designated the departments or agencies to be used in carrying out its mandate, Congress authorized the President to utilize such existing departments or agencies as he might designate to carry out his “pet project.”126

The President lost no time in setting up the overhead administrative machinery of the Civilian Conservation Corps. On the 5th of April he created127 the Emergency Conservation Work organization, with Robert Fechner, a former lecturer on labor questions at Harvard and Dartmouth colleges,128 as Director. Although the terms of his appointment made the Director responsible for carrying out the provisions of the Conservation Act his work is that of general supervisory control.129 Upon appointment, Director Fechner laid down the general policies guiding the establishment and operation of the camps.130

An advisory council, including representatives from each of the four executive departments designated to aid in carrying out the program, was set up to cooperate with the Director in the establishment and operation of the conservation camps.131 The Secretary of Agriculture appointed Major R. Y. Stuart, Chief of the Forest Service; the Secretary of the Interior, Horace M. Albright, Director of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations; the Secretary of Labor, W. Frank Persons, Director of the United States Employment Service; and the Secretary of War, Colonel Duncan K. Major, Jr., of the General Staff.132

The Department of Labor, acting through designated State Directors of Selection was chosen to select the experienced woodsmen and the enrollees from eighteen to twenty-five years of age, or Juniors, exclusive of Indians and Veterans. The Indians and some non-Indians on the reservations are selected and enrolled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior, while the Veterans are selected by the regional managers of the Veterans’ Administration.133 The conservation workers in Alaska and Puerto Rico are selected through the Forest Service and those in Hawaii by the National Park Service.134

The War Department, functioning through the Corps Area Commanders and the liaison officers at Corps Area headquarters, enrolls, assigns, replaces, and conditions all the enrollees of the Civilian Conservation Corps proper. It also has charge of camp operations, recreational and welfare activities, and the disbursing and accounting work in these camps, while the educational training is under the general supervision of the Department of the Interior.135 The work projects are under the direction of the Agriculture, the Interior and War departments. The Department of Agriculture, operating through the Forest Service, plans and supervises the conservation work on national forests, including Alaska, Puerto Rico, Oregon and California railroad land grant; executes camp projects for the Navy on naval reservations and for the Tennessee Valley Authority; and supervises the planning and execution of forestry and erosion control work projects on state and private lands. The Department also carries on several projects through the Bureau of Animal Industry and the Bureau of Biological Survey. The Department of the Interior, through the National Park Service, the Office of Indian Affairs, the General Land Office, the Bureau of Reclamation and the Soil Erosion Services is responsible for the technical administrative supervision of conservation work on lands under its control. It also supervises the work in state, county, and metropolitan parks; and erosion control work on private lands under the Soil Erosion Service. The War Department, acting through the Office of Chief of Engineers, operates the war veterans’ camps engaged in flood control work. The Department also supervises the work projects on military reservations.136

The selection of the camp sites was naturally given to these three Departments since they had to be located near suitable conservation projects. It has been the policy of the camp selecting agencies to locate as many of the men as possible on work projects within their home states137 This, however, could not be done during the first and second camp periods when site selection depended largely upon the supply of work of the type authorized by the reforestation act.138 The states with large forested areas, especially California, were allotted more camps than they normally would have had,139 in as much as most of the densely populated states were unable to furnish projects for their quotas.

Mobilization of the C. C. C.

In order to carry out the President’s wish to have 250,000 men at work in the nation’s forests by early summer,140 the various agencies selected to administer the program did not wait until the Emergency Conservation Work legislation was passed before going to work. The Forest Service in cooperation with other agencies, in response to Senate Resolution 175, dated March 10, 1932; had just completed an intensive study of the forest situation in the United States,141 and, therefore, was ready to begin work on its part of the program. The project supervising agencies had until the middle of July to complete their plans and get their administrative machinery in full working order, since the Civilian Conservation Corps would have to be selected and conditioned before the project work could begin. On the other hand, the Labor and War departments had to make arrangements to select, enroll and condition the men at once.

On the 3rd of April the President announced that he wanted the first men enrolled by the sixth of that month. This assignment called for immediate action on the part of the Department of Labor. Its representative on the Advisory Council, W. Frank Persons, realized that he had no time to set up a nationwide organization of his own for the selection of 250,000 men from among all who might apply. 142 Moreover, he had no desire to form such an organization but preferred to use organizations already familiar with the unemployed youth in the particular localities and well qualified to choose the type of men desired. With only three days in which to organize these selecting agencies so they could begin the enrollment of the first 25,000 on April 6, Mr. Persons invited the representatives of the various relief agencies of the seventeen largest cities in the country to meet with him in Washington.143

Representatives of the Agriculture, the Interior and War departments and from the Director’s Office also participated in this meeting. Detailed discussion of the Civilian Conservation Corps program was held and visiting representatives were asked to take over the job of selecting the initial group of enrollees. Instructions were immediately wired to the local welfare agencies of the representatives’ twelve states, and selection of the men began.144 The selecting organization was perfected by the designation of a State director of selection to act as the representative of the Department of Labor in each State.145 The entire quota of 250,000 men was selected within thirty days, and from that time on additional men were furnished for replacements as fast as the Army Corps Area commanders notified the selecting agencies that additional workers were needed.146

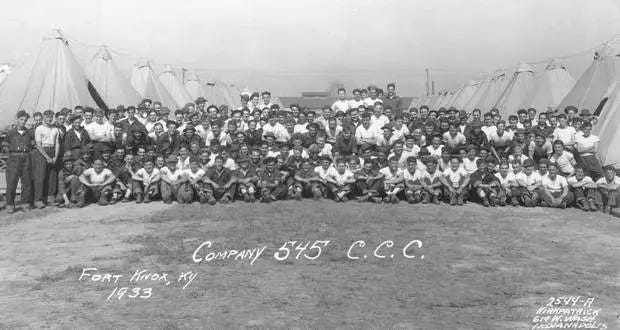

The biggest job of the whole Emergency Conservation Work program was given to the Army. To establish thirteen hundred and thirty forest camps on a three thousand mile front from the Atlantic to the Pacific, distributed in depth from Canada to Mexico, and occupying every state in the Union except Delaware, and to move 55,000 of the men a distance of over 2,000 miles from the Atlantic seaboard to the Rockies and the Sierras, would take careful planning and enormous effort, even though there should be no administrative or legislative delay.147 It was not necessary to wait until the legislation was passed before going to work. In fact, the Army had made plans for a similar program before the New Deal came into being.148

As early as January 10, 1933, Senator Couzens introduced a bill in Congress to provide for the sheltering and feeding of indigent, transient youths by the Army.149 Later it took definite form as an amendment to the Army Appropriation Bill and called for the caring for some 88,000 young men as a charity measure, but it failed to become a law.150 Nevertheless, the War Department, aware of the Couzens scheme, immediately made plans to carry out the proposal in case it became a law. With the failure of its adoption the Army merely laid its plans away against possible future use.151 The occasion came when the President proposed his Civilian Conservation Corps idea at the White House Conference on the 9th of March.152 Under orders from the Commander-in-chief, the Chief of Staff on the same date requested the preparation of regulations for the reception, organization and care of the enrollees.153

By the 24th of March, while the Joint Committee of Congress was still holding hearings on the Emergency Conservation Work bill, “the General Staff had prepared in draft form, complete regulations governing the administration and supply of the . . . Corps ready for issue in the field.” They defined the Army’s task, its relation to the other cooperating agencies in the program, and set up probable quotas for the various Army Corps Areas, estimating unit costs covering clothing, medical attention, shelter, subsistence, supervision, welfare, equipment for project work, and transportation to and from camp. The following day secret radio messages outlining the field work of the Army in the new program were sent to the Corps Area Commanders.154 In this manner, except for last minute modifications, the Army was prepared for its work before the discussion of its authority began in Congress.

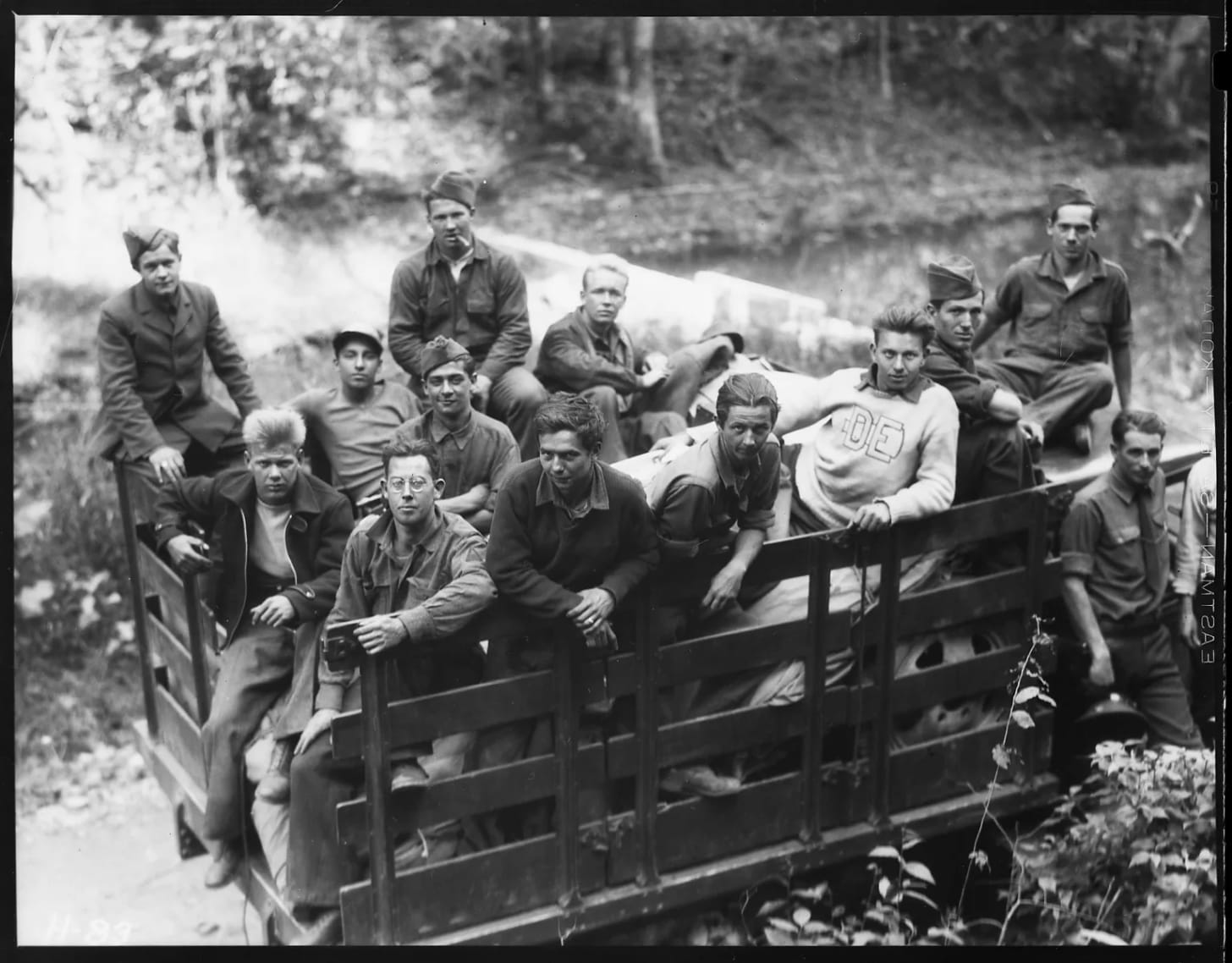

It has already been pointed out that the conservation bill as finally passed left most of the details to the discretion of the President. Especially did this apply to the relationships that would obtain between the various departments in charge of the program. The executive order establishing these relationships was drafted while the bill was still in Committee, but was, of course, modified, as were the Army regulations, to coordinate them with the plans of the other departments concerned, before final passage of the measure. The Director’s approval of the War Department’s regulations governing its part in the administration of the emergency conservation program and agreement with the Department of Labor in the matter of selection and enrollment of the men was secured by the 5th of April On that date all Corps Area Commanders again received orders assigning their duties and directing them to enroll the first contingents the next day.155 The Third Corps Area selected the first man in the so called “peace time army” on the anniversary of the Nation’s entrance into the World War.156 Two days later, the actual enrollment, consisting of Juniors and the local experienced woodsmen, was 1,366.157

A month later there was an actual enrollment of only 50,347 men.158 This delay called for quick action if the President’s objective was to be reached. On May 12, after enabling legislation had been enacted, the President approved a program that authorized an enrollment of 274,375 and would place 250,000 men at work in the forests by the first of July. To accomplish this it was necessary that the full number of men be on hand by the seventh of June; that two weeks must be allowed for their reception and conditioning, and one week for transportation and establishment in camp; that some additional 222,000 men, at an average daily rate of 8,540 had to be enrolled and organized; that around 1,200 more company units had to be organized and equipped at the rate of twenty-seven per day; that approximately 1,300 work camps had to be set up at the rate of twenty-six per day; and that 55,000 of the men had to be transported a distance of 2,000 miles.159

The four cooperating agencies worked at top speed in order to carry out to the letter the President’s instructions. The Forest Service and the National Park Service rushed to completion a two year forest work program which normally would have been spread over a ten year periodic Their immediate work in order to get the program under way was to select from a thousand to fifteen hundred of these previously planned work projects, scattered throughout the most inaccessible portions of the country, suitable in character and location for the program. This done, the next step was the selection of suitable camp locations for the company units of inexperienced youths who were to work these forestry projects. After the sites are selected they are given a number, the letter symbols indicating the type of camp and the numbers the rank in point of selection. Thus S-51, stands for a project on a State Forest; F, or NF-4, on National Forest; P-68, on Private Land; E-5, Erosion Camp; NP-6, National Park; and SP-17, State Park.161 These Services, furthermore, had the task of selecting, procuring and distributing tools, machines, trucks, for each project Finally, it was necessary to select, assign, and instruct suitable supervisory men with highly specialized knowledge of the work as well as the ability to lead.

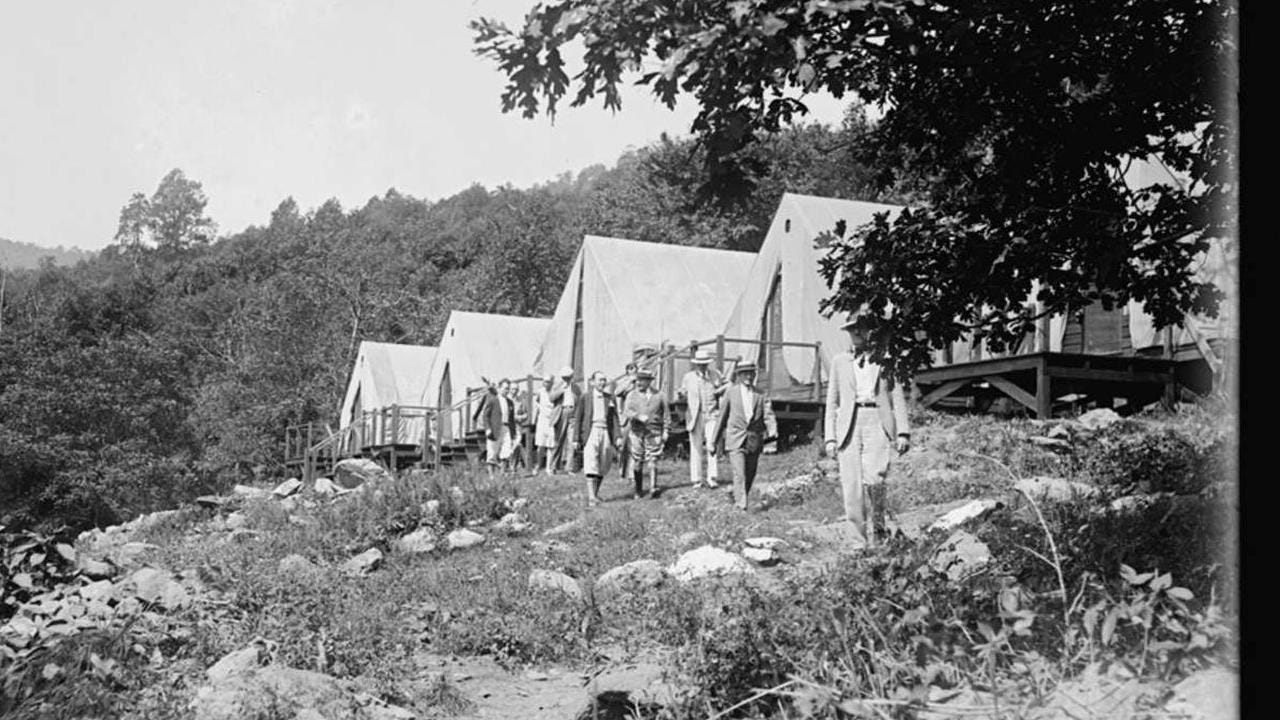

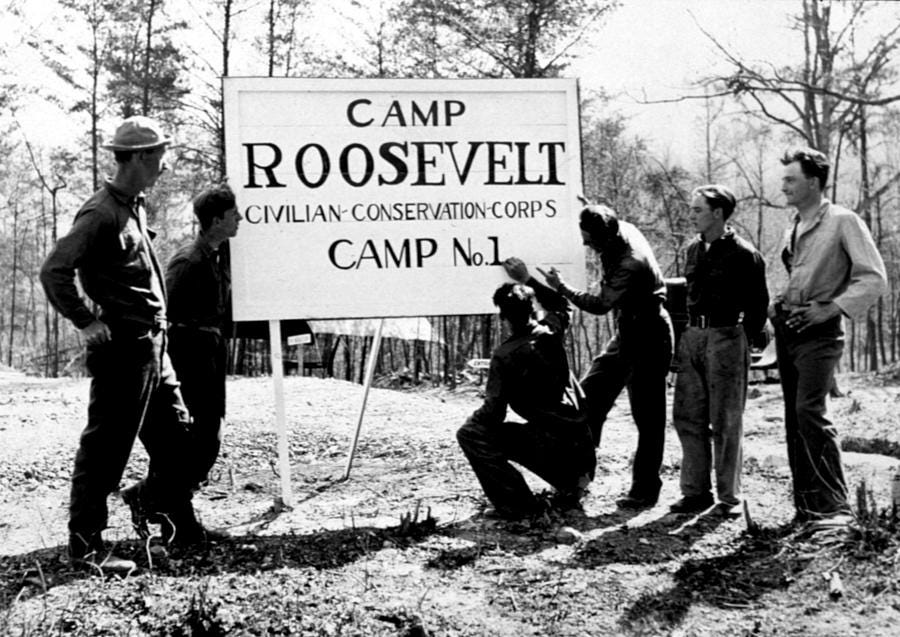

The first camp was established in the George Washington National Forest, at Edinburg, Virginia, April 17, 1933.162 it received the Federal Civilian Conservation Corps number of F-1, and was appropriately named Camp Roosevelt. The Company, Number 322, was organized at Fort Washington, Maryland. Practically one-third of its members were from Virginia and the rest from the District of Columbia. The men, all white, were from the eighteen to twenty-five year old group.103 By April 19, one hundred and seven camps located in regions Seven and Nine of the national Forest Service had been approved.164 A month later one thousand camps had been selected, although only fifty-two had actually been established. The selected camps, dotting every section of the United States, included sixteen at military posts; six hundred and fifty-five in national forests, sixty-three in National Parks, one hundred and twenty-four in State Parks and one hundred and forty-two on private lands. One-half of the established camps were in the Third Corps Area, twelve in the Sixth, six in the Eighth, five in the Ninth, two in the Seventh, and one in the First. There were none in the Second, Fourth or Fifth Corps Areas.165

By June 20, thirteen hundred and thirty forest camps had been established. 166 At the end of the first camp period there were fifteen hundred and twenty camps in operation. Twelve hundred and sixty eight of these, including five in Puerto Rico and one in Alaska, were established by the various Services of the Department of Agriculture; two hundred and forty-three by the Department of the Interior; and nine by the War Department.167

During the second period the total number of camps was increased to fifteen hundred and twenty-eight by the addition of eight Indian camps, increasing their number to seventy-five. The number in Alaska was increased to three and that of Puerto Rico to six. The total number of camps given does not include those established by the Department of the Interior in Hawaii in this period. Here the work was distributed over four of the Hawaiian Islands, and counted on the company quota basis the number of camps would be six, bringing the total number of work camps for the second period up to fifteen hundred and thirty-four.168 Counting each company of approximately two hundred men as a camp, the grand total of camps for the second period was 1,548 instead of 1,534. The authorized quota of 1,468 for the Civilian Conservation Corps proper was retained by the establishment of new camps for those abandoned on account of climatic conditions.169

The fifteen hundred and thirty-four camps were divided as follows: Forest Service, 1,140, a decrease of one hundred and twenty-five under the first camp period; Biological Survey, two, a decrease of one; Bureau of Animal Industry, one; National Parks, sixty-seven, a decrease of three; State Parks, two hundred and thirty-nine, an increase of one hundred and thirty-seven; Bureau of Indian Affairs, seventy-five, an increase of eight; and the War Department, ten, an increase of one. With the establishment of two camps in Delaware every State in the Union, the District of Columbia, and each of the principal outlying possessions had one or more camps. There was also a marked decrease of camps in the Ninth Corps Area and an increase in the number east of the Rocky Mountains.170 This shift from West to East was made possible to a large extent by the acquiring of nearly half a million acres of land through gift and purchase by the states for state parks and forests171 and the acquisition of some half million acres of forest-land, situated in twenty-three of the states east of the Great Plains, by the federal government,172 and the establishment of camps thereon.173 During the first camp period only twenty-six states had state park camps while in the second period this number was thirty-two.174

In the third period the total number of camps jumped from 1,534 to 1,731. They were divided as follows: Forest Service, 1,143, an increase of three over the previous period; Biological Survey, three, an increase of one; Bureau of Animal Industry, one; National Parks and Monuments, one hundred and nine, an increase of forty-two; State Parks, three hundred and twenty-five, an increase of eighty-six; Office of Indian Affairs, seventy-seven, an increase of two; General Land Office, one; Bureau of Reclamations, seven; Soil Erosion Service, thirty-four; Office of Chief of Engineers, twenty-two, a decrease of six; War Department’s other project work, nine, an increase of two. The large increase in the total number of camps for the third period was due primarily to the establishment of one hundred and seventy-one drought relief camps. Ninety of these camps were established by the Forest Service, fifty-two by the State Park Work organization and the remainder by the other project administration agencies of the Interior and War depart-ments.175

The total number of camps in operation during the fourth and final period of the initial program was 1,740.176 They were divided as follows: Civilian Conservation Corps camps, 1,640; Indian group camps, eighty-five; and territorial possession camps, fifteen.177 Several hundred were transferred to new locations or relocated on old sites. The distribution of the camps among the various project supervising services was practically the same as in the previous period. Every State, the District of Columbia, and the principal territorial possessions had one or more camps. The conservation work in the Virgin Islands was authorized during this period. It is under the supervision of the National Park Service.178

After receiving the President’s program calling for quick action in the establishment of the conservation work, the Department of Labor completed the selection of its quota of 274,375 men practically ahead of schedule.179 It also selected replacements for each camp and mid-camp period as they were needed.180 The record of the selection of the Indians by the Office of Indian Affairs was equally as good, even, though actual enrollment was deferred from the 14th of April to about June 23, 1933.181 The selection of the war veterans for the first period continued without interruption from June 12, until its completion July 31, when the enrollment reached 26,838, including 2,042 Bonus Marchers enrolled at Fort Hunt.182

The State quotas of all men selected for the first camp period, exclusive of those assigned to territorial possessions, were 314,236. Of this number 239,125 were Juniors, 35,250 experienced woodsmen, 25,000 veterans, and 14, 861 Indians.183 The quotas for the second camp period remained the same as the first, except that of the Veterans, which was increased to 28,225. This increase added to the 2,377 quotas of Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico provided for the selection of 319,838 men for conservation work during the second six months of the program.184 During the third camp period the authorized number was increased to 369,838 by the additional 45,000 Juniors and 5,000 Veterans allotted to twenty-two drought stricken states.185 The authorized strength for the fourth and final period of the initial program was 371,922. This number was divided as follows: 290,000 Juniors, 33,225 Veterans, 30,000 local experienced woodsmen, 14,400 Indians, and 4,297 residents of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.186

In order to keep the enrollment of camps near their authorized strength, a system of replacements, which provides for the filling of all vacancies every three months, was inaugurated.187 Replacements since the close of the first camp period have been as follows: October and November, 1933, 125,000 to take the places of the summer camp enrollees who were discharged at or prior to the end of the first camp period;188 January, 1934, 25,000 authorized to bring the strength of each camp to two hundred men;189 April and May 1934, 100,000 to replace j the men voluntarily discharged prior to the opening of the third camp period on the 1st of April;190 July, 1934, 110,000 replacements for approximately 70,000 “full service” men automatically discharged because of the one-year service limit, and 40,000 who had dropped out to accept employment or for other reasons;191 October, 1934, approximately 100,000 to bring the forest camps to their authorized strength of 369,838;192 and January, 1935, 68,000 to fill vacancies which occurred during the first part of the fourth period.193

The War Department broke all American mobilization records in the first three months of the reforestation program. During that time the Army enrolled, conditioned, and transported to camps more men than it mobilized during the first three months of America’s participation in the World War.194 By May 27, 1933, with the addition of the first contingent of Veterans, the enrollment had exceeded 154,000 men, and by the first of July it had surpassed the objective of 250,000 by approximately 29,500. The peak of the enrollment for the first camp period was reached on July 22, when it stood at 301,230. Of this number 269,339 were Juniors and experienced Woodsmen; 26,371 Veterans, and 5,520 Indians.195 The latter group, of course, was enrolled by the Office of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior.196 The total does not include about 10,000 in the Army administrative personnel,197 and approximately 15,000 of the project personnel.198

By the last month of the first camp period the enrollment had dropped, from its high point in July, to 248,740. The workers were divided as follows: Forest Service, 201,806; National Park Service, 28,717; Office of Indian Affairs, 13,069; Office of Chief of Engineers, 3,554; Bureau of Biological Survey, 489; General Land Office, 193; and territorial possessions, 912. Those enrolled in the territorial possessions, of course, were under the supervision of the Forest Service or the National Park Service. The average daily numbers employed on field work was 182,946 and for camp duties 62,964.199

The enrolled men were permitted to re-enroll for the second six month period and 175,000 took advantage of this privilege. Replacements were added from time to time, and a slight increase in the Veterans’ quota and enrollment in Hawaii was authorized. The peak enrollment for this period was reached on January 15, 1934, when it stood at 305,857.200 By the end of the period there was a considerable drop in the enrollment, especially in the Civilian Conservation Corps proper, which dropped from 289,184 in January to 211,747.201

The highest enrollment for the third period was on August 14, 1934, when it reached 359,070. This large increase over the second period was due primarily to the 50,000 drought relief enrollment.202 The peak enrollment for the fourth camp period was reached on October 30, 1934, it totaled 361,786 men.203 This number included 282,273 Juniors, 34,628 experienced woodsmen, 32,802 Veterans, and 12,083 Indians. In addition to the enrolled men there were 24,212, including approximately 18,000 superintendents and foremen, members of the project supervisory personnel; 5,939 Army reserve officers assigned to camp administration; and 1,109 educational advisors employed in camp and project administration.204

Conclusion