Flashback: "Grab the Revolution by the Throat"

How Pyotr Stolypin wiped out Russia's leftist violence and almost saved an Empire

This was the first article to be published on this Substack, and one of the most relevant to today. In light of the growth that’s occurred over the last few months I’ve decided to repost this article for free to allow recent subscribers to enjoy it. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work and gain access to all articles and podcast episodes.

Although many know about the 1917 Russian Revolution that deposed the Czar and eventually led to the establishment of a communist regime in Russia, relatively few are aware that the Russian Empire went through another cataclysmic social upheaval a little more than a decade before its final collapse.

The 1905 Revolution followed Russia’s disastrous military defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. Seeing Russia humiliated on the global stage caused social and political chaos throughout the Empire, culminating in a tidal wave of terrorism.

More than 8000 political murders occurred in just two years. Most of the victims were low level officials and innocent bystanders. Tens of thousands of politically motivated robberies, kidnappings, and extortions accompanied the bloodshed, nominally to fund more revolutionary activity.

All economic life was affected. Trade and employment were disrupted, exacerbating tensions even further. Money was not safe in banks or, as brutal home invasions became more common, even in private homes. Bombings, arsons, and assassinations became weekly, or in some places daily, occurrences. Russia had fallen under a kind of mass hypnosis. People were killed for pocket change in the name of the Revolution. The response from the public was apathy, paralysis, or even nihilistic enthusiasm for the forces tearing society apart. And then, just a few years later, it stopped.

The man most responsible for an end to the terror was Pyotr Stolypin, the Prime Minister and Interior Minister of Russia from 1906 to 1911. Born to an aristocratic family, Stolypin spent nearly his entire life in service to the Russian state. He first occupied a series of low-level administrative positions, giving him a ground-level view of normal peoples’ problems, before rising to the role of Governor in one of Russia’s poorest and most dangerous provinces, Saratov. Saratov was a hotbed of revolt because of unstable land conditions.

Russia had a special class of peasants called serfs who were tied to the land that they worked, controlled by noblemen or large landowners. Although Czar Alexander II abolished serfdom in 1861, the land wasn’t given to the serfs to be owned in individual plots. Instead, it was distributed to village communes. These communes offered none of the incentives of private ownership and distribution of land, surplus, and other essentials of agricultural life was often very unfair.

The arrangement left nearly everyone unsatisfied. Violent political movements were able to get widespread public support by proposing any changes at all to this system. Despite these challenges, Stolypin was one of the only governors in the Russian Empire who was able to keep firm control of his territory during the start of the 1905 Revolution. This remarkable success led Czar Nicholas II to appoint him to the highest positions in Russia’s civilian government.

Although the land question was an ever-present part of Russian political life, other, more existential, issues also caused major unrest. Russia’s Imperial system, with roots dating back to the Middle Ages, was criticized as antiquated and repressive when compared to the parliamentary governments popular in Europe at the time. Many progressive-minded Russians demanded major political changes that ranged from the creation of a more representative government, to the abolition of the death penalty, to the end of the monarchy altogether.

As a compromise near the start of the 1905 Revolution, the Czar had surrendered some of his authority and created a parliament called the Duma. However, the Czar’s concessions, effectively made at gunpoint, were not received with gratitude. The Duma was dominated by radicals of all sides, many of whom were openly hostile to the government itself. The loosening of restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, done to appease Russian liberals, seemed to have only made criticism of the government, and the violence that followed, more intense.

Stolypin understood that first and foremost a government must be resolute. One of the biggest problems facing Russia was that the ideas nominally driving the Revolution enjoyed widespread popularity, even within the government itself. For decades, all educated classes had been inundated with the idea that social change, and the eventual implementation of liberal policies, was inevitable and good. This idea was present in books, plays, and popular songs, and carried with it enormous social pressure to conform.

Politicians, officials, even judges, often viewed the perpetrators of revolutionary violence as misguided rather than a lethal threat to the public. As a result, although on paper the consequences for terrorism were severe, in practice leniency was the order of the day. Prisons were understaffed and guards were often indifferent to smuggling and even escape attempts. Many prisoners exiled to hard labor in Siberia viewed their punishment as a vacation. One police officer stated after yet another round of light sentences were handed down by the court:

“The latest verdicts in political trials are truly horrifying, for after several months, all those convicted, having spent their terms in confinement, return to the path of revolutionary activity with redoubled energy. In reading such verdicts one really loses heart and all energy. . . . What is the use of wasting money on the investigation and detainment of people who will be locked in prison for several months at best and then let loose with an opportunity to go back to their previous work?”

The government’s passivity in the face of behavior that demands a response created a societal meltdown. Government officials were attacked in broad daylight with no consequences. The perception that the central authority was unable or unwilling to preserve itself greatly accelerated the attacks. Police began to make deals with revolutionary groups for their safety, if they didn’t just abandon their posts first. Everyone was afraid to defend themselves, lest they be tried in secret by a “revolutionary court” later and targeted for assassination. Eventually, the public began to act as though there were no central authority at all. Criminal violence surged right alongside political violence to the point where it was impossible to separate the two.

The main solution to this was found in emergency military courts, known as field courts martial, created by Stolypin to handle cases of terrorism. Local governments were authorized to hand over suspects who were caught in the act, or whose substantive guilt was so clear that a formal investigation was not necessary, to these military courts. A typical defendant would be an assassin tackled after shooting a policeman in public or someone found with large amounts of bombmaking material in their home. Unlike the traditional Russian legal system, which might take months or years to handle a regular criminal case, emergency courts were required to convene within 24 hours of the arrest and reach a verdict just 48 hours after trial began.

Instead of highly educated legal professionals, men who could come up with very creative reasons to ignore the obvious, the judges were panels of 5 military officers appointed by the local commander. Defendants had no right to a lawyer, the trial was not open to the public, and the verdict could not be appealed. Most severe of all, sentences, including the death penalty, were to be carried out within 24 hours of a conviction.

Although these measures were widely condemned by liberal and conservative lawyers alike, who recognized that the emergency courts offered far fewer protections against abuse and injustice than the normal legal system, they were very effective in securing convictions and severe sentences. In the first 8 months of the program, more than 1000 accused terrorists were convicted and executed by the emergency courts.

However dubious from a human rights perspective they may have been, these convictions and executions had a real impact on the ongoing epidemic of terror. In the Baltics, a region of the Russian Empire that had been paralyzed by widespread violence, murder and arson cases were reduced by 66% in just 30 days. Further illustrating the emergency courts’ effectiveness: when the law authorizing the courts briefly expired, revolutionary violence doubled that following month.

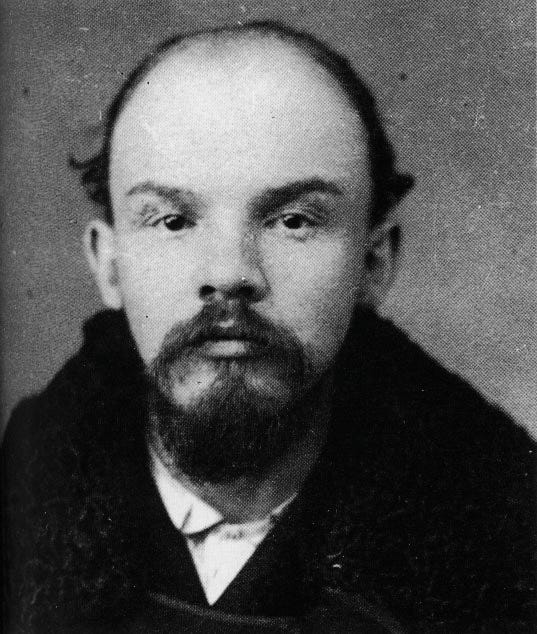

In what was probably the highest endorsement of the emergency courts, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, who would later successfully topple the Russian government and kill millions of Russians in 1917, briefly returned to Russia from exile in 1905. The widespread chaos and violence of that revolution led him to believe that he could operate with greater freedom than ever before. He quietly fled the country again in 1907, citing concerns about Stolypin’s rough justice. Lenin would not return to Russia until after Stolypin was long-dead.

The reputation of these emergency courts became so fearsome that the hangman’s noose became colloquially known as “Stolypin’s necktie.” The introduction of immediate and harsh consequences for terrorism broke the spell that Russia had fallen under. Both the perpetrators and enablers of this behavior were allowed to see, in the most direct way possible, that the process of social unwinding was not inevitable and that carrying on had real risks. In an interview, Stolypin said “I have grabbed the revolution by the neck and I will strangle it, if I myself remain alive.”

Anarchy had been replaced by harsh but predictable rule of law, and once again there was a normal life to return to. However, Stolypin was not interested just in interrupting revolutionary terror with a dispassionate state violence of his own. Unlike most conservative government officials of the time, Stolypin understood that the best way to short circuit support for terrorism was to address the motivations of revolutionary activity, while cutting out the revolutionaries from the process.

Once while speaking to the liberal members of the Duma, Stolypin stated: “We are not frightened. You want a great change. We want a great Russia.” For too long, the stagnation of the Russian state had allowed terrorists to cloak their actions in legitimate grievances, gathering public support for murders, bombings, and robberies that normally everyone would have opposed. Having proven through his military courts that the government would not be intimidated into making political concessions, Stolypin embarked on his own series of substantive economic reforms to craft a system with widespread public support.

He drafted new legislation to transform the communal agricultural system into one based on individual ownership of private property. By creating millions of new small farms, Stolypin hoped to not just make the economy more efficient, but also to build a new class of small landowners who would be firmly invested in the stability and future of Russian society.

These reforms were opposed by both the Right and the Left in the Duma. Rightwing members of parliament were concerned about the threat these new small farms might pose to the large agricultural concerns that had traditionally dominated the Russian economy. Leftists hated the departure from communal economics and social relations, understanding that these new private landowners would fight to keep what they had.

Stolypin’s relationship with the Duma was hostile, to say the least. As Prime Minister, Stolypin interfered with the rules of parliament to secure passage of government-supported legislation. When the second session of the Duma displayed radical tendencies, he ordered the Duma dissolved and had members of parliament who had associated with terrorists arrested. He rigged election rules to ensure that future parliaments would have far more cooperative legislators. Young, brawny, intelligent, and unbending, Stolypin was a living reminder that the Imperial system still had some vitality left in it. When peace and reform finally came to Russia, the public saw that it was not through compromise with or surrender to the revolutionaries, but rather through the determined effort of conservative government officials alone.

Although these measures made Stolypin hated by politicians, he was able to implement parts of his new political program to great success. Special banks were created to lend peasants the money required to buy their own land. The country underwent a massive economic boom. Crop yields and exports soared. With this new economic prosperity came a decisive fall in crime. Although in 1907 there were thousands of recorded incidents of political violence in Russia, in 1912 there were just 82 in the entire Russian Empire. Terrorist behavior became so dangerous for the perpetrators and unpopular with the public that in 1909, the leadership of the once all-powerful Socialist Revolutionary Party formally voted to end its terror campaign in cities and the countryside.

Stolypin proved himself to be ruthless in justice and politics, but the biggest contributor to his legacy was his enormous personal bravery. Even as a low-ranking official, Stolypin was known to travel into dangerous areas without bodyguards to address the public directly. This bravery continued as he rose in rank. During the 1905 Revolution, he never once bent to revolutionary mobs. Instead, he adopted then-cutting edge police tactics like creating a unified file system to track those suspected of terrorist activity. After he became the Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior, he was one of the highest priority targets for revolutionary assassination.

There were eleven attempted assassinations on Stolypin in total. The worst occurred in 1906, after Stolypin dissolved the Duma. Stolypin was hosting a reception at his home on Aptekarsky Island when Socialist Revolutionaries wearing military disguises dropped bombs in the crowd. 28 people were killed in the ensuing explosions. Stolypin’s 15-year-old daughter lost both her legs and later died while being treated in the hospital. His son suffered a broken leg. Stolypin himself was miraculously unharmed, having stepped into his office to take a meeting just before the blast.

Facing the worst tragedy a parent can endure, Stolypin displayed his characteristic resolve. Rather than resigning or retreating from the hardline policies that made him so hated and feared by the revolutionaries, he moved into the home of the Czar himself and resumed his work almost immediately. Eventually, after conquering the culture of mass violence that had crippled the government, he attempted to create a new peace that could last for generations. He focused on resolving ethnic tensions and worked with religious leaders to create a new vision for the future of the state, different than the ones liberals had been setting out for decades.

Sadly, Stolypin’s many successes would eventually give way to sabotage. In 1910, his enemies in the Duma gained the political capital required to end the expansion of his successful land reform policies. Although he won the war against terrorism and economic instability, his critics never forgave him for his ruthless governing style and set about driving him and his projects out of the government altogether. In 1911, he resigned from his position and Czar Nicholas began looking for a successor.

The Czar quickly realized that no one could fill Stolypin’s shoes and attempted to entice him back into government, but this revelation came too late. On September 14, 1911, Stolypin was shot multiple times by a Socialist Revolutionary while attending an opera performance in Kiev. The Czar and his eldest daughters personally witnessed this shooting. Even after being fatally wounded, Stolypin never forgot his duties and motioned for the royal family, then rushing to his aid, to back away in case there were more assassins in the crowd. He died four days later.

Stolypin’s victories were of the most tangible kind a government official can achieve. He took a nation overrun with horrific violence and gave it peace. He took a nation plagued by economic inefficiency and backwardness and gave it seemingly endless growth. The rising tide lifted all ships. Nearly everyone in Russia, from the richest to the poorest, could benefit from Stolypin’s reforms. Sadly, these reforms would not last. Stolypin was one of the fiercest advocates against involvement in foreign wars, saying that Russia needed another two decades of peace for his plans to take full effect. In his absence, pro-war voices gained the majority in Russian politics.

The First World War created conditions for enormous social upheaval. Without efficient and unshakable high level officials like Stolypin, the Russian Empire was once again unable to stop the contagion of political violence. In 1917, the Czar was deposed and a weak liberal government took power. A few months later, the Bolsheviks seized control of the country. The rest is history. Tens of millions would die in the ensuing civil conflicts, famines, and Red Terror. The Russian Empire would be replaced by the Soviet Union. This totalitarian communist system, created by the successful revolution, proved to be far more unfair and unjust than the counterrevolutionary program Stolypin was so bitterly criticized for.

As Americans face economic uncertainty and a rapid increase in senseless violence, they must learn from the successes and failures of those who came before them. The problems we face today are not new, and they’re not unsolvable. The challenge is finding the will to think outside of the box and follow through. If the Russian Empire could halt its civilizational death spiral with just one Pyotr Stolypin, imagine what the United States could do with a dozen, or a hundred, or a thousand.

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe to support my work and receive future content.

McMeekin has high praise for Stolypin in his book “The Russian Revolution: A New History”.

It should be an inspiration and a hope to all that one man can indeed make a difference and he doesn’t have to be a terrorist or maniac to do it. He needs to crave a sense of normalcy and be willing to do what’s hard.

This was a terrific article--thank you. Although the stick is more sensational, it's important I think to remember his use of the carrot too, as you did. I remember a quote from the great Three Who Made a Revolution by Wolfe, that one of the three (Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin... I think it was Lenin; I read it 30+ years ago) accounted the Stolypin-Witte agrarian reforms as true reforms, and as the biggest threat to their revolution, and one of the reasons to hurry its coups forward. NB This around around the time half of my great grandparents immigrated to the USA from these trouble lands, thank god.