Two intelligence reports from the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, 1919

Please read these

The American intervention in the Russian Civil War was a confused and frustrating effort. Although charitable organizations like the American Red Cross made Herculean efforts to relieve the suffering of Russian civilians caused by the devastating famine and fuel shortages under Bolshevik misrule, the U.S. military was largely hamstrung by Byzantine foreign policy interests and public war fatigue.

President Wilson wanted to resolve the matter as quickly as possible, while both the Japanese and the British intelligence services hoped to profit from the dissolution of one of their biggest rivals, the Russian Empire. The specifics of this disaster will require a separate article to explore. In this entry, I just wanted to replicate two reports (one complete and on partial) written by an intelligence officer with the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia so that I could refer to them easily later. I really do recommend reading them, particularly the second report, as they do a great job capturing the role that public morale (or rather, the lack of it) plays in revolutionary environments.

One note, these reports are pretty hard to find. Although I have no reason to doubt their authenticity (I’ve seen them quoted partially elsewhere), I found them in an online entry that apparently contains the FBI file on Harold Noel Arrowsmith, Jr., obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. Arrowsmith was a far right publisher who had been questioned over bombings in the Civil Rights Era. As far as I can tell, Arrowsmith quoted the reports in some of his literature, leading the FBI agents investigating him to request the original reports from the National Archives for his file.

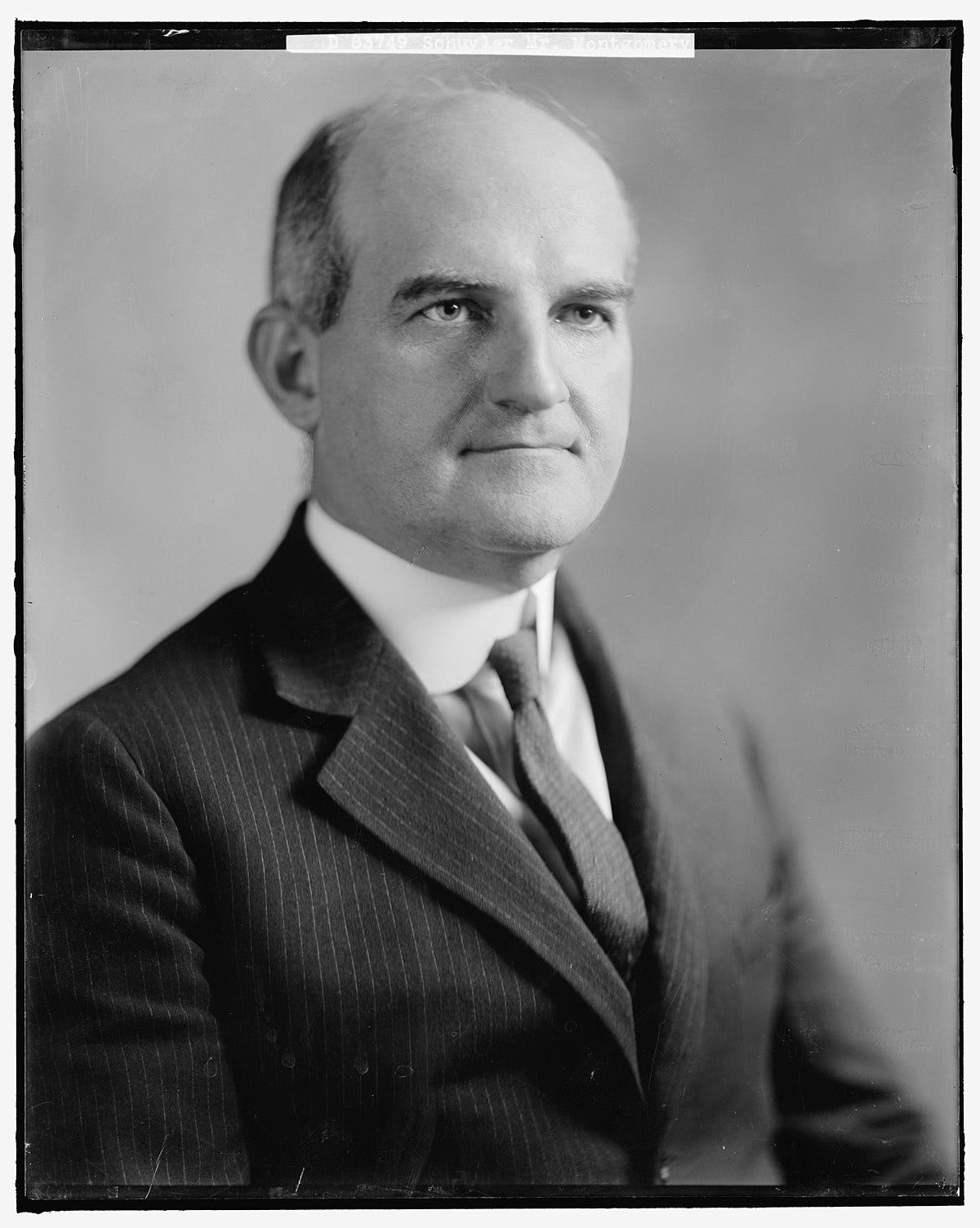

The intelligence officer who wrote the reports was Captain Montgomery Schuyler. Schuyler was a career diplomat who had served in a series of prestigious posts in Russia, Japan, and Latin America before WWI. He was the lead intelligence officer in Omsk, Siberia (which had a large concentration of American forces) during the Russian Civil War, and was promoted to Major before the war’s end. Afterwards he would resume his diplomatic duties, taking a prominent role with the American mission in El Salvador, before moving to banking.

As with all historical documents, the more extravagant claims should be taken be taken with a grain of salt unless they can be verified. In particular, I’m skeptical of the specific numbers Schuyler references from the April 1918 article by Robert Wilton (which I was unable to locate) in the second report. Although Jews were overrepresented among the Bolsheviks, particularly in political and intelligence roles, and there was an enormous amount of cooperation with the Bolsheviks by American radical groups and “fellow travellers,” without being able to look at the table myself I doubt that their proportion among commissars, especially those who had travelled from America, was quite that high.

Rather than focusing on specifics, I hope that these reports, in a more general sense, illustrate just why Americans who had served in Russia had such a visceral negative reaction to the prospect of Bolshevik rule, and the social unrest and official passivity that enabled it, in America. These attitudes contrast with the open embrace of Bolshevism by many liberal activists, politicians, and labor organizers of the time.

Although Schuyler did not have all the information we have today available at his fingertips, as a seasoned and respected diplomatic officer his observations on the fall of the Kolchak government have great value. This was not some quack.

Report of March 1, 1919, from Captain Montgomery Schuyler to Lt. Colonel Barrows, Vladivostok.

PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL

March 1, 1919.

My dear Colonel Barrows: I have just received your letter of January 29th, forwarded by Baron Hoven of General Romanovsky’s staff, who has just arrived in Omsk. I was of course interested in your news, as I had been unable to find anything about the movements of our officers or as to myself.

I was afraid that I should be stranded in Omsk for some little time even if the others got away and although I want to get home just as soon as possible for urgent personal business reasons, I realize that I am of more use here than possibly anywhere else. This work, however, is so familiar to me as this is the fifth revolution I have watched in the pains of birth, that I must confess it has lost the charm of novelty.

I have not attempted to write you anything concerning the situation in Omsk as I have felt the conditions here were so fluid that what I wrote would be valueless when received by you. Lieutenant Cushing is preparing a sort of weekly report which he will send in his own name and which will suffice us both for the present. My telegrams have been perhaps more numerous than you desired and some of the subjects mentioned may not interest our expedition in the least. This I was aware of when sending them but I felt it was better to err on the side of fullness than the other way. I am strictly obeying my orders to keep out of local affairs and avoid giving advice, but I must say it is very hard not to jump in and manage this government entirely.

The problems which the Omsk Government has to face are not at all intrinsically different from those which prevail in every movement of the kind known in history, but the besetting problem in this instance is that Admiral Kolchak has to work with the materials available for his purposes, namely the Russian people of today, who are so thoroughly disorganized and lifeless as a result of the last three years, that they are unable even to think for themselves far less to govern themselves.

In the first place, the coup of Admiral Kolchak’s friends whereby he secured the role of Supreme Governor was absolutely necessary if the whole of Siberia was not to fall ripe into the hands of the Bolsheviks. That visionary set of impractical theorists with whom I spent an entire evening in a railroad car at a Manchurian station—Messrs Aksentieff and company—were far worse than out and out anarchists, for they were weak dreamers who could not even maintain the ordinary police security necessary for life in any community. Crime was rife in the streets of Omsk, murders and hold ups were of nightly occurence in this city on the main streets and the Bolshevik city governments throughout Siberia were running things their own way just as they are in Vladivostok today.

It is of course difficult to legalize Admiral Kolchak’s position, in fact it is impossible, for while it was done by the decree of the so called government of the time, it was simply a coup d’etat. His status however is as good according to Russian law as that of any of the revolutionary governments which preceded him.

In the beginning and of necessity his acts for the restoration of order were autocratic; he depended on the support of the army and the officers especially, and he put down local disorder with a high hand.

Ever since then however, he has shown himself in so far as he could safely do so, more and more liberal, and I have no hesitation in saying that I firmly believe that his own opinions and frame of mind are far more liberal than the outside world gives him credit for. He is unfortunate in this that he has had to depend upon the mailed fist to maintain his position and to keep his government from being overrun by the Bolshevik elements that are numerous in every city in Siberia.

It is probably unwise to say this loudly in the United States but the Bolshevik movement is and has been since its beginning guided and controlled by Russian Jews of the greasiest type, who have been in the United States and there absorbed every one of the worst phrases of our civilization without having the least understanding of what we really mean by liberty. I do not mean the use of the word liberty which has been so widespread in the United States since before the war began, but the real word spelt the same way, and the real Russian realizes this and suspects that Americans think as do the loathsome specimens with whom he now comes in contact. I have heard all sorts of estimates as to the real proportion of Bolsheviks to that of the population of Siberia and I think that the most accurate is that of General Ivanov-Rinov who estimates it as two percent. There is hardly a peasant this side of the Urals who has the slightest interest in the Bolshevik or his doings except in so far as it concerns the loss of his own property and, in fact, his point of view is very much like that of our own respectable farmers, when confronted with the IWW ideal.

Unfortunately, a few of our people in the United States, especially those with good lungs, seem to think that the Bolsheviks are as deserving of a hearing as any real political party with us. This is what the Russian cannot understand and I must say that without being thought one sided, I would not hesitate to shoot without trial if I had the power any persons who admitted for one moment that they were Bolsheviks. I would just as soon see a mad dog running about a lot of children.

You will think I am hot about this matter but it is I feel sure, one that is going to bring great trouble to the United States when the judgment of history is all recorded on the part we have played it is very largely our fault that Bolshevism has spread as it has and I do not believe we will be found guiltless of the thousands of lives uselessly and cruelly sacrificed in wild orgies of bloodshed to establish an autocratic and despotic rule of principles with which have been rejected by every generation of mankind which has dabbled with them.

There have been times during the past month when I have been afraid that the Kolchak government would not last until the next morn. I have had I suppose, the closest connection with the leaders here of any foreigner in Omsk and my sources of information are so many and so varied that I am pretty sure to hear the different points of view on every imaginable question. The announcement of the Princes Island conference with the Bolsheviks came as a clap of thunder to the government in fact it took the wind out of their sails, that I believe they would have thrown up the government and run away if it had not been for timely and cool headed advice which they received. When the news became more widely known there was a fairly strong reactionary movement started by Cossack officers and adherents of the old regime. This was discovered and allowed to die a natural death with very good results. With the failure of the Princes Island conference, the government began to get back a little of the strength it had lost and today I believe it will hold on for some time, provided it does not get another series of hard knocks from the Allies or the United States.

The very clever and most unscrupulous Japanese propaganda which has been carried on here is one of the most interesting I have ever seen carried out by that country. The way the Japanese took over Korea and we made a scrap of paper of our solemn treaty with that poor little miserable people was child’s play to the present methods of procedure in regards to Kex [?] Siberia. Admiral Kolchak hates the Japanese and the latter naturally are not unaware of that feeling and cordially reciprocate it and the combination of their propaganda with that of the Bolsheviks in the United States and elsewhere is very powerful. I can understand how people who know nothing of our foreign relations or of the Russian people can be carried off their feet by it but how responsible men can listen to it I do not know. If the feelings of the Russian people are to be consulted and the future of their own country is to be in their hands there will be no Bolshevik future of this land. They have submitted to it first, from the very good reason that they did not know how to go about fighting it and second, because it came at the psychological moment when the morale of the people had been so shaken that they were ready to endure anything in order to be allowed to be let alone.

The scheme now being worked out for a popular assembly for all parts of Siberia will, I am sure, be of service and even if only partially successful—and I do not see at present how it can be more—will do much towards proving the sincerity of Kolchak in his promises.

Please do not get the idea that I am enthusiastically in favor of the present government, that I consider it ideal or even good, for it is not; but I do consider that it has already united more varied and more numerous elements of the Russian people than any other government which might take its place would do. The question of the moment is not an ideal government but one that will last of the next few weeks and will restore order enough so that any elections may have a fair chance of being carried out without force and fraud and graft.

Personally, I am fairly comfortable here; Cushing and I have each a room requisitioned by the government and it will be impossible to carry out the recommendations made by the Adjutant in a recent telegram because there are no rooms to be had and we have had applications for two months already. With kind regards to all friends,

I am very sincerely yours,

Montgomery Schuyler

Captain, USA

Lt. Col. Barrows,

Vladivostok.

Report of June 9, 1919, from Capt. Montgomery Schuyler to the Chief of Staff, A.E F., Siberia (pp. 1 and 2 only).

HEADQUARTERS, AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES, SIBERIA

Vladivostok, Siberia,

June 9, 1919

From: Captain Montgomery Schuyler

To: The Chief of Staff

1. In compliance with orders of the Commanding General (Secret) October 25th, 1918, I left Vladivostok on November 20th, 1918 and proceeded to Omsk which I reached on December 8th, 1918. I left that city, also in compliance with orders, April 26th, 1919 and arrived in Vladivostok on May 7th, 1919.

2-5. Full and accurate information as to the "local personalities" at Omsk is rather difficult as both military and civil officials of the government there are constantly changing and since my departure there· have been many new appointments in both the Cabinet and War Ministry. The Government as at present administered consists of first, Admiral Kolchak, with the title of "Supreme Ruler.” On the civil side the Government consists of a Council of Ministers presided over by the President of a Council of Ministers. This Council at the present time is forced to do both legislative and executive function. On the military side the Admiral has the so-called "Stavka" or General Staff and the Minister of War which is one of the divisions of the civil cabinet. Up to the time of my departure the General Staff and the War Ministry had separate heads and their respective functions were constantly causing friction owing to the lack of clearly defined spheres of activity. Since then, however, they have been united under one man who is the Chief of both divisions and this change it is believed will bring· about greater unity and coordination in the military work. The General Staff is in charge of all matters pertaining to the front and to the active campaign against the Bolsheviks. The Ministry of War is charged with the duties of mobilization, transport, and supplies as well as of all military operations in the rear, which term is now used to include all territory East of Omsk. With the great gain of territory which have been made by the army this Spring, it has been found necessary to have the General Staff nearer to the actual theatre of operations and preparations are now being made to move it from Omsk to Ekaterinburg. Admiral Kolchak has stated that he will not move the civil government from Omsk until he is able to take it to Moscow or Petrograd.

Both the civil and military departments at Omsk, at the present time, suffer from the lack of men trained in leadership and of executive ability. When Admiral Kolchak came in power he found no men in the government who were capable of filling the offices they held, with the possible exception of Mr. Vologodsky, the President of the Council of Ministers. Nearly all of the other ministers were of the long-haired, loud-mouthed type and spent so much time in fruitless discussion that they were never able to get any action even on the most urgent matters. These men are gradually being replaced as new men can be found of greater executive ability and there is a steady but slow improvement in the calibre of the ministers. It must be remembered, however, that owing to the geographical limitations, Admiral Kolchak had only Siberia to draw from and Siberia has never been known as a breeding place for Russian statesmen, on the contrary it has always been the dumping ground of persons whose presence in European Russia was not desired by the Government. Practically none of the trained officers of the old army are now available, those of them that survived the war with Germany having nearly all been murdered by the Bolsheviks as they were found in European Russia. In the Black Sea Massacre it is stated that not less than 8,000 officers were murdered and at Kronstadt, in the Gulf of Finland, between six and seven thousand were drowned at one time. The present officers of the Siberian Army are either former non-commissioned officers of the old army or young boys who have had just sufficient education to be able to do the necessary paper work and neither kind are of the right stamp to reorganize a new army and to hammer out a fighting force from the hopeless anarchy into which Kerensky and his successors, Lenine [note: this was the most common English spelling of “Lenin” name at the time] and Trotsky, have thrown the Russian people.

At the time when Admiral Kolchak took over the Government in November 1918 as the result of a coup d’etat which was engineered by the Cabinet during the Admiral's absence at the front in an effort of the more sensible members to get rid of the paralyzing influence of Avksentiev and his followers. Almost immediately after this Admiral Kolchak had pneumonia and it was not until January 1919 that a real beginning was made in the reorganization of Russia. Up to the end of 1918 things had been growing steadily worse in Russia ever since the first few months of the First Provisional Government, when for a short time it looked as if the new regime would be able to bring some sort of modern government into the country. These hopes were frustrated by the gradual gains in power of the more irresponsible and socialistic elements of the population guided by the Jews and other anti-Russian races. A table made in April 1918 by Robert Wilton, the correspondent of the London Times in Russia., showed that at that time there were 384 "commissars" including 2 negroes, 13 Russian, 15 China, 22 Armenians and more than 300 Jews. Of the latter number 264 had come from the United States since the downfall of the Imperial Government.

[further pages of this memo weren’t included by the National Archives because they apparently discussed other unrelated matters]

That’s all. The parallels between the Russian Civil War and conditions in America today (crime, passivity, sophistry, etc.) really are striking. Hopefully we’ll see more from Captain Schuyler soon.

Thanks for sharing this. The utter contempt with which the Bolsheviks are treated in official reports from on-the-ground professionals like Schuyler is illuminating.

Our support for the Bolsheviks will go down as one of the most heinous acts of ignorance and hubris in history. I think it will only be exceeded by our support for Mao.