Very funny find: Free anti-John Brown Western made during the 1940s

Ride with the devil

Longtime readers of this Substack will be very aware of my opinion that anti-slavery terrorist John Brown was one of the greatest villains in American political history.

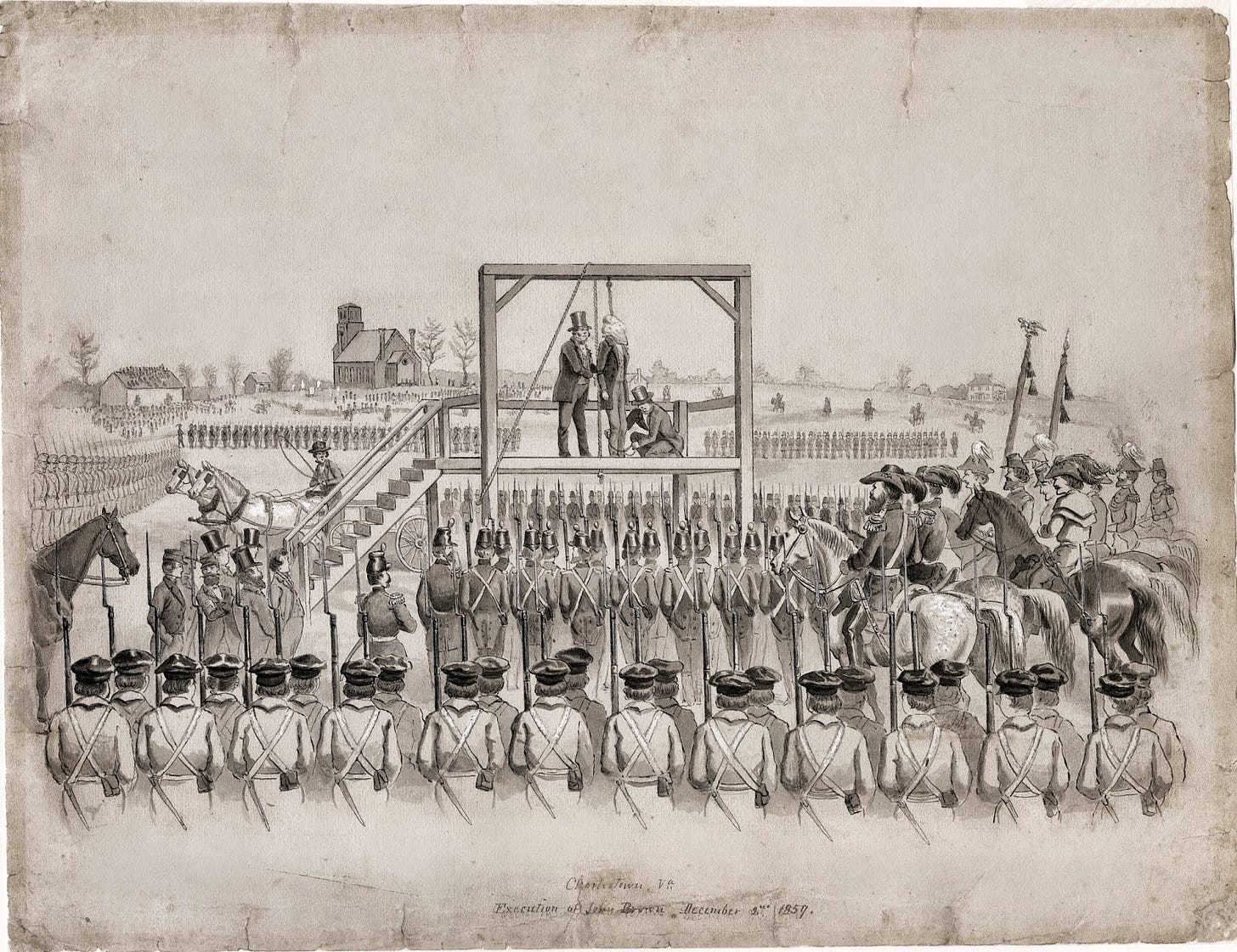

Brown was regarded by his contemporaries as a demented serial killer who reveled in terrorizing innocent people, a traitor whose political radicalism were a cloak for base resentments and mental illness, who met his very well-deserved end at the gallows (One interesting fact I recently learned: Brown was the first American ever to be executed for treason). He very nearly succeeded in destroying our country. Few people bear more direct responsibility for engineering America’s preventable and tragic Civil War, and the millions of deaths that accompanied it, than John Brown.

Brown’s current reputation as a crusading freedom fighter is a relatively recent invention (beyond the efforts of various abolitionists who used Brown as a troll to express their hatred of white Southerners) that flows almost solely from our intellectually bankrupt and hopelessly compromised education system, obviously designed to erect the mental scaffolding for similar revolutionary anti-white terror targeted at innocent civilians in the minds of countless generations of libtards.

I’ve recorded three podcast episodes related to Brown. The first is on the book “War to the Knife,” which covers the Bleeding Kansas Crisis (the bloodiest period of which was kicked off by Brown’s brutal execution of 5 unarmed civilians in a single night). The second covers the film Ride with the Devil (1999), which is probably the best movie on the American Civil War, covering the irregular conflict in the Kansas and Missouri territories. The third is on the book “A Disease in the Public Mind,” which presents a novel (and convincing) theory that it was actually Massachusetts that caused the Civil War. Tragically, all three of these podcast episodes are free.

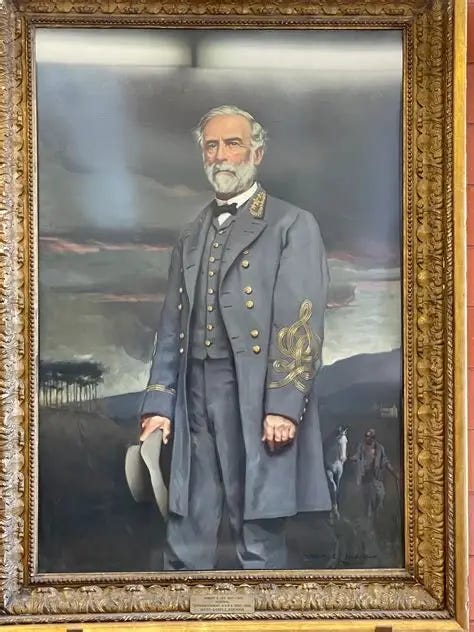

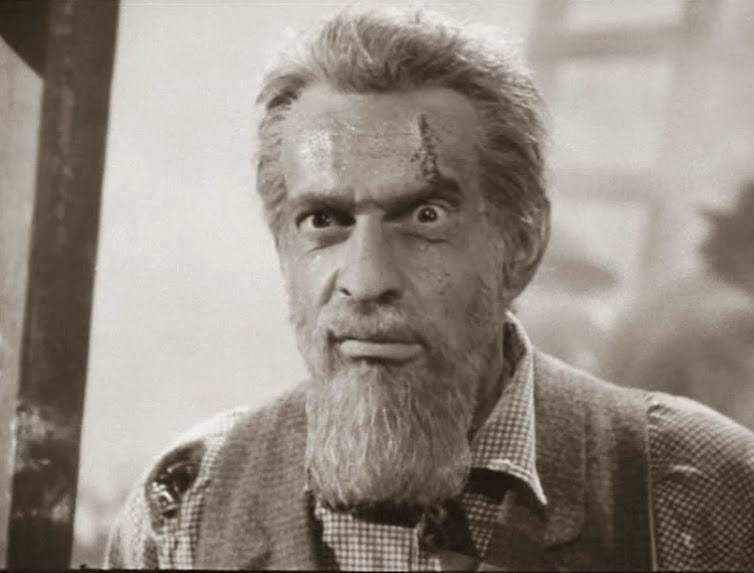

Imagine my pleasant surprise when I learned that there was actually an anti-John Brown Western made during 1940s. The film is Santa Fe Trail (1940), which stars Errol Flynn as future Civil War hero J. E. B. Stuart, who encountered Brown first as a young cavalry officer assigned to patrol the Kansas-Nebraska territory during the Bleeding Kansas Crisis, and then, by sheer coincidence/fate, during Brown’s infamous Raid on Harper’s Ferry, when Stuart volunteered to serve as Robert E. Lee’s aide-de-camp as Lee led the U.S. Marines who responded to Brown’s raid and eventually captured him. It was Stuart who walked into the killzone to offer Brown surrender terms and Stuart who signaled the final assault with a wave of his hat after those terms were refused.

You can watch the complete movie for free below:

Santa Fe Trail is pretty good as far as Westerns from this period go. Standard action, romance, etc. Raymond Massey, the actor who plays John Brown is fantastic as the villain. It’s uncommon for Brown to be portrayed in this way at all, making it all the more impressive that Massey managed to convey the darker side of Brown’s personality without descending into parody.

The movie certainly plays it fast and loose with history in several major ways, such as introducing George Custer of Little Bighorn fame (played by future President Ronald Reagan) as Stuart’s sidekick, although the two men never encountered each other except when their respective units faced off on the battlefield at Gettysburg. The film’s depiction of the Harper’s Ferry Raid is nothing like the actual event.

One aspect of this film that I really liked was that it goes out of its way to show how prominent the major players of the Confederacy were in American society before the Civil War. There’s an extended cameo where future CSA President Jefferson Davis, at the time of the story the US Secretary of War, delivers a speech at Stuart’s graduation ceremony at West Point. The American Civil War really was a brother war. These guys all knew each other. There was no good reason that these all these great people, with roots together that went way back, had to end up killing each other in such large numbers. Malignant types like Brown and the film’s fictional abolitionist West Point cadet Carl Rader worked very hard to make the conflict inevitable.

If you’d like to read more on this period, I’d recommend “Shelby Foote’s The Civil War: A Narrative” and Stephen E. E. Ambrose’s “Duty, Honor, Country: A History of West Point.” I’m planning on recording podcasts on both of these eventually, though I’m still figuring out what I’m going to say.

The next podcast episode, on a grab bag of Xbox 360 WW2 shooters and historical revisionism more generally, should hopefully be wrapped early next week. However, this upcoming episode will be reserved exclusively for paid subscribers. If you’re a free subscriber who’s read this far down: Unironically man, fuck you.

Most recent podcast episodes:

Ep73: I hated normieslop F1 the Movie (2025) in a way I didn’t think possible (Paid)

Ep69: Zen police ultraviolence simulator Ready or Not (2023) is the only game for our time (Paid)

Ep68: “Days of Rage” is the most important book for you to read today, right now (Paid)

Ep66: Mission Impossible has fallen (Paid)

Ep65: The definitive introduction to LOST: Season 1, objectively the best television ever produced (Paid)

In a lot of ways, John Brown was really the first free subscriber

Also, since I know our host is fond of historical lost books, a very valuable pre Civil War book to read for someone who wants to understand the origins of the Civil War is Hinton Helper's 1857 "The Impending Crisis" (https://archive.org/details/DKC0147/mode/2up). This book, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin, was one of the major pre-Civil War abolitionist publications that helped mobilize public opinion against the South (it was a best seller in the North and banned in the South under penalty of death, several people were hanged for owning it). Besides being an abolitionist, Helper was a Southerner, a racist, and a white supremacist (and by white supremacist I mean he lived until 1909 and as far as I know never wavered in his belief that all black people should be removed from the United States, financed to resettle in Africa or Latin America, and replaced by white immigrants).

The whole book is an incandescently angry screed against what he called the "Oligarchy" of slave-owners (more typically called "the slave power" in politics of the time) for basically completely wrecking the South -- destroying the economy, prosperity, development, and moral character of the region. It's fallen into some obscurity today because of Helper's politics ("Once for all, within a reasonably short period, let us make the slaveholders do something like justice to their negroes by giving each and every one of them his freedom, and sixty dollars in current money ; then let us charter all the ocean steamers, packets and clipper ships that can be had on liberal terms, and keep them constantly plying between the ports of America and Africa, until all slaves shall enjoy freedom in the land of their fathers") and also because a lot of it is a rather dry compendium of statistics (it's actually very impressive what he does statistically all by hand, hundreds of years before computers). Those statistics make a devastating case about the underdevelopment of the South in every way.

It's not an easy book to read straight through but it really takes you inside the free soil ideology and mentality and demonstrates how slavery was seen not as a fundamentally racial issue but an issue about opposing systems of ownership of human beings by an oligarchic minority vs. social and economic liberty for all. E.g. Helper accuses proponents of slavery of being "negro- worshipping" oligarchs who "support the worthless black slave and his tyrannical master at the expense of the free white laborer" -- this is the mentality that needs to be understood.