What happened when the only son of an American president to fall in combat was killed

If I Die in a Combat Zone...

Quentin Roosevelt was the youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt, just 3 years old when his father was elected to the nation’s highest office. He had the unusual distinction of growing up almost entirely in the White House.

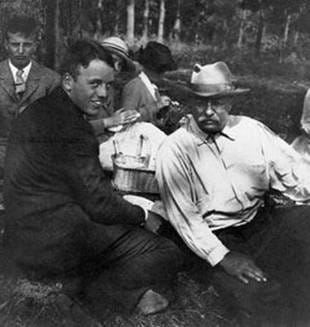

The senior Roosevelt cast a larger-than-life figure, having overcome asthma at a young age through a vigorous exercise regime. After he conquered his illness, he embarked on a series of adventures—from becoming the youngest NYPD Commissioner in history to starting over as a cattle rancher out West—well into his middle age. He was certainly aware of his own reputation. He was also very media-savvy. Quentin, an intelligent and happy child, was often at the center of positive stories covering the Roosevelt family.

Newspaper readers were captivated by the exploits of the mischievous Quentin and his friends, dubbed “The White House Gang.” He built a baseball diamond on the White House lawn and terrorized Secret Service agents with often dangerous building projects and experiments. The extent to which these things were staged for PR purposes is a bit up in the air, but it’s still fun to think about. Imagine a real-life Richie Rich. The public got to watch Quentin grow up.

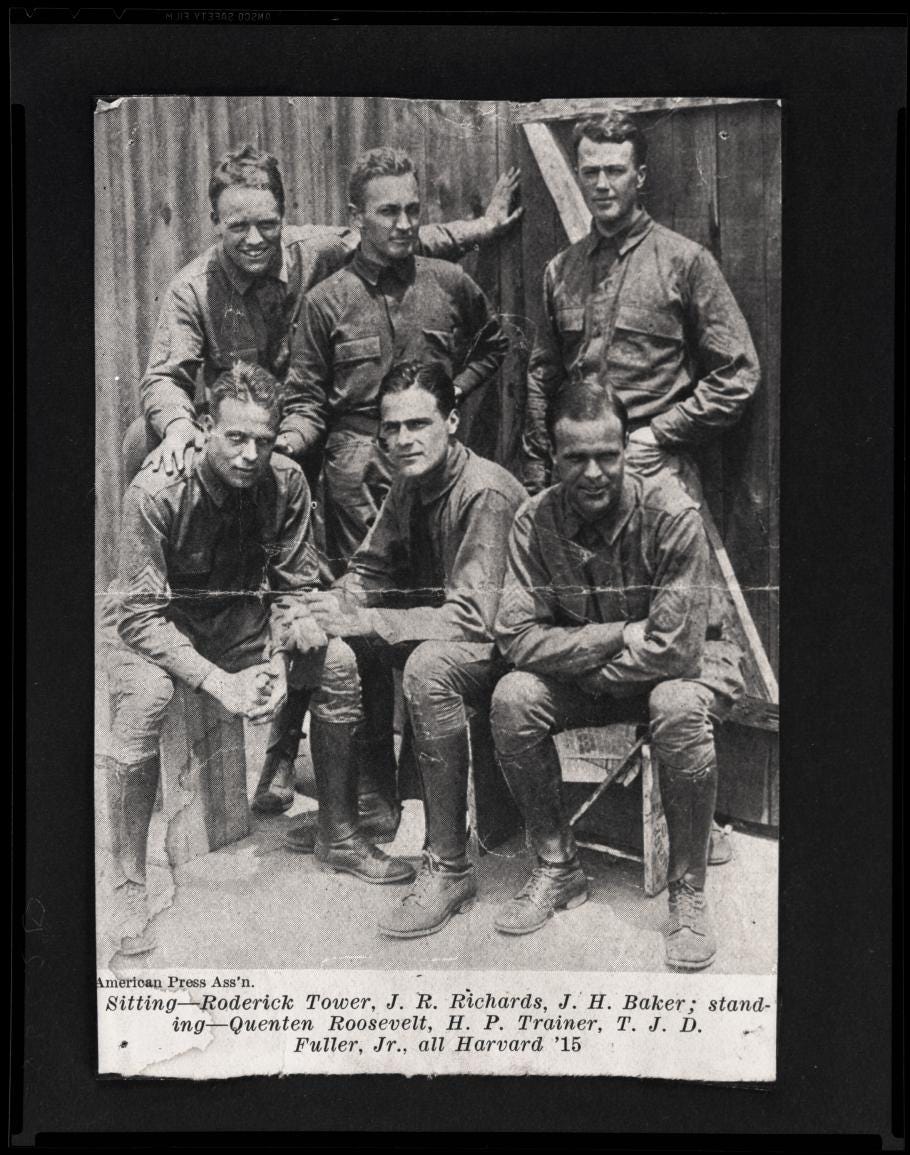

World War I began when Quentin was attending Harvard University. Although the US was neutral at the start of the conflict, Theodore Roosevelt (no longer in the White House) organized a series of summer military training camps for businessmen and university students. When the US finally entered the war, these men were offered commissions as officers based their on performances. Eventually these summer training programs would be legally transformed by Congress into the modern ROTC program.

Quentin attended one of these camps and did well despite having to adapt considerably to military life. It was obvious that he was his father’s favorite child. The two looked very similar and were almost identical to each other in temperament. Quentin would often accompany his father on big game hunts.

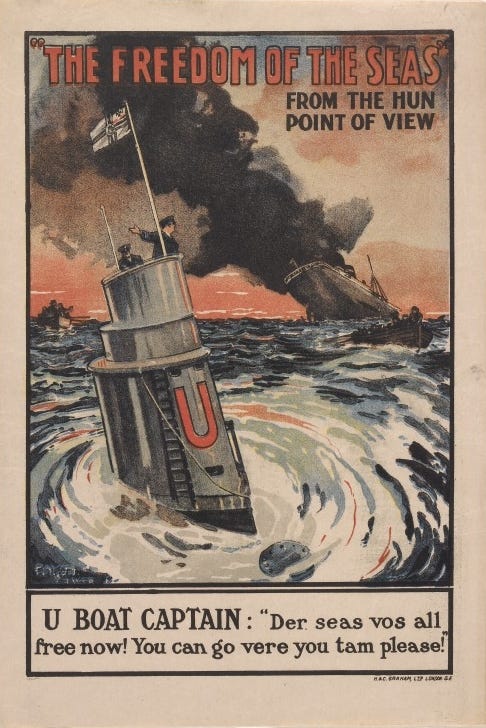

Both Quentin and his father were angered by the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German submarine. Although the ship was nominally a civilian passenger liner, it was secretly carrying millions of rounds of ammunition and artillery shells in its cargo hold. 128 American civilians, all just normal commercial passengers on the ship, died during the sinking.

The sinking of the Lusitania became a major focus of propaganda efforts to end America’s neutrality in the war. Information that the ship was surreptitiously carrying huge amounts of war material, giving weight to German claims that it was a legitimate military target, was carefully concealed from the public.

This incident and other anti-German propaganda narratives (which often involved fake claims of over-the-top atrocities committed against civilians in Belgium) primed the American public for entry into the war. After the Zimmerman telegram, proposing a (wildly unrealistic) alliance between German and Mexico for an attack on the United States, was intercepted by the British, direct US intervention became inevitable.

When war was declared, Quentin volunteered immediately. Because of his mechanical skills, he was drawn to the Army’s burgeoning Air Corps (the Air Force did not exist yet). The First World War saw the birth of combat aviation. Although Quentin knew how to fly, he initially served as his unit’s supply officer and helped supervise a training airfield in France. He was very popular among the men, despite his lofty background, and developed a reputation as an efficient and energetic officer.

Because combat aviation was so new, pilot training was rushed. The aircraft were very primitive. Technology that enhanced pilot survivability hadn’t even been invented yet. Airborne weapons were very inaccurate beyond 100 meters, if they worked at all. Aerial engagements, known as “dogfights,” happened exclusively at close range. They were fast and brutal, with extremely high casualties. The life expectancy for a new combat pilot during WWI was between 40 and 60 hours of flight time.

This was due in large part to the steep learning curve. While pilots from the earliest days of the conflict might have thousands of hours of non-combat flight training, new pilots had barely any experience before being thrown into the fray. The difference in quality between experienced and inexperienced fighter pilots was like night and day.

Furthermore, at the start of American involvement in the war, there was little attention paid among the Allies to the importance of coordination between fighters. German squadrons were known for their sophisticated group tactics. Manfred von Richthofen, “The Red Baron,” had 85 confirmed aerial victories. He was the deadliest Ace of the war despite being greatly outnumbered and flying an aircraft that was far less maneuverable than his opponents’ in most engagements.

Fully understanding the risks, Quentin eventually volunteered as a combat pilot. He got his first confirmed victory a day after he arrived on the front lines, shooting down an enemy fighter during the start of the 1918 German Spring offensive. This was the last major effort the German military would undertake, a desperate gamble to split the Allied force in two and force a ceasefire.

Just four days later, Quentin would participate in a large dogfight at the commencement of the Second Battle of the Marne. The German daily newspaper Kölnische Zeitung contained a detailed account of the engagement:

The aviator of the American Squadron, Quentin Roosevelt, in trying to break through the airzone over the Marne, met the death of a hero. A formation of seven German airplanes, while crossing the Marne, saw in the neighborhood of Dormans a group of twelve American fighting airplanes and attacked them. A lively air battle began, in which one American (Quentin) in particular persisted in attacking. The principal feature of the battle consisted in an air duel between the American and a German fighting pilot named Sergeant Greper. After a short struggle, Greper succeeded in bringing the brave American just before his gun-sights. After a few shots the plane apparently got out of his control; the American began to fall and struck the ground near the village of Chamery, about ten kilometers north of the Marne. The American flier was killed by two shots through the head. Papers in his pocket showed him to be Quentin Roosevelt, of the United States Army. His effects are being taken care of in order to be sent to his relatives. He was buried by German aviators with military honors. The German pilot who shot down Quentin Roosevelt told me of counting twenty bullet holes in his machine when he landed after the fight. He survived the war but was killed in an accident while engaged in delivering German airplanes to the American Forces under the terms of the Armistice.

Although Quentin was initially reported Missing-in-Action, his death was soon reported by another American pilot who had participated in the battle.

By sheer happenstance, an American soldier who had been captured during the German offensive was present at the funeral conducted by the German military several days later and recorded what he saw:

In a hollow square about the open grave were assembled approximately one thousand German soldiers, standing stiffly in regular lines. They were dressed in field gray uniforms, wore steel helmets, and carried rifles. Near the grave was a smashed plane, and beside it was a small group of officers, one of whom was speaking to the men. I did not pass close enough to hear what he was saying; we were prisoners and did not have the privilege of lingering, even for such an occasion as this. At the time I did not know who was being buried, but the guards informed me later. The funeral certainly was elaborate. I was told afterward by Germans that they paid Lieut. Roosevelt such honor not only because he was a gallant aviator, who died fighting bravely against odds, but because he was the son of Colonel Roosevelt whom they esteemed as one of the greatest Americans.

Theodore Roosevelt’s enormous popularity with Germans likely owed to his adventures in the American West as a young man. Western novels, particularly those of Mexican-American war hero Thomas Mayne Reid, were extremely popular in Europe at the time and (slightly fictionalized) accounts of Roosevelt’s exploits sold thousands of copies across the globe.

A member of the German propaganda ministry took a photo of the crash site, with Quentin’s uncovered body still in view. The photo was briefly sold as a postcard, but this disrespect to a fallen enemy created such a scandal with the German public that these were quickly taken off the market.

American troops soon recaptured the village where Quentin had been shot down. His grave was marked, as was the custom for downed fighters, with his plane’s broken propeller blade and wheels.

The French military constructed a far more elaborate wooden enclosure for the grave. The site quickly became a sort of shrine for Allied troops in the area, and was often visited by dignitaries and newly-arrived American soldiers who wanted to pay their respects. The original German-made wooden cross that marked Quentin's grave was moved to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Quentin’s body was eventually moved to the World War II American Cemetery in France at Colleville-sur-Mer, which was created to house the numerous American dead killed during the D-Day landings. He was reburied alongside his oldest brother, Brigadier General Ted (Theodore III) Roosevelt, who died of a heart attack shortly after personally leading troops ashore at Utah Beach. Ted was more than 50 years old and had severe arthritis and heart issues, forcing him to walk with a cane, when he volunteered to go in with the first wave. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on the ground that day.

Theodore Roosevelt would never recover from Quentin’s death. He slipped into a deep depression and began advocating for very harsh treatment of defeated Germany after the war. He died less than 6 months after Quentin did.

The story of Quentin Roosevelt is a great look at a very different era in American and world history. The past is a foreign country. It’s hard to imagine anything like this happening today, much to our detriment.

Beautiful tribute. Teddy and Quentin are American legends. Sadly Teddy IV supported the removal of his great grandfathers statue from the Museum of Natural History in NYC.

It is almost impossible to think of a situation today where an enemy would treat someone actively trying to kill their compatriots with such respect. Thank you unidentified former book publisher for another great article justifying my continued subscription