ACLU hero Clarence Darrow bribed juror to try to free bombers who killed 21 people

The model civil rights lawyer

Please note, this article is part of an ongoing series on the first Red Scare. The first two entries of the series cover the trials of Sacco and Vanzetti and a series of forgotten socialist church invasions in 1914. Although this article is free, the rest of the series is paywalled. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work, every new subscriber makes a difference.

Clarence Darrow is one of the most famous lawyers in American history. Millions have seen the film Inherent the Wind (1960) dramatizing the Scopes Monkey Trial in which Darrow famously argued against a Tennessee law that banned the teaching of evolution in schools.

Darrow’s views and methods were extremely influential. He defended people considered indefensible in his time: millionaire thrill killers, assassins, blacks accused of raping white women, and even terrorist bombers. His clients were to be given every benefit of the doubt. Rather than focusing solely on the facts, Darrow placed cases in the larger context of popular progressive causes of the day.

Darrow was a competent and eloquent trial lawyer. His closing arguments lasted for hours, sometimes days. Of the fifty accused murderers he defended, only one was ever executed: Patrick Eugene Prendergast, a deranged man who shot the Mayor of Chicago to death. Darrow attempted to have him found not guilty on the grounds of mental insanity. Prendergast was hanged on July 13, 1894.

Darrow was known as a lawyer who could pull a rabbit out of a hat. His clients could be unambiguously guilty, yet Darrow would pursue every trick in the book (and a few outside of it) to have them acquitted on any grounds. His commitment was ideological. Darrow’s parents were both lifelong activists. Darrow was an enormous patron of liberal causes, an influential figure in Chicago machine politics, and widely considered in progressive circles to be a fighter who could always get things done.

It was this reputation that led Darrow to be hired to defend the McNamara brothers, J.J. and J.B. The brothers were organizers for the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers (IW), a prominent labor union in the Los Angeles area. Although the union had had some successes since it was created in 1896, by 1910 they had been run out of many foundries and mills.

In response to these setbacks, the IW began a terrorist bombing campaign. Between 1906 and 1911, the union and its affiliates blew up 110 iron works using dynamite. There were hundreds of bombings, but the damage was usually slight and very few were injured.

One of the biggest critics of unions during this period was the L.A. Times. The newspaper’s publisher, Harrison Gray Otis, was an arch-conservative who wanted to rid the city of Los Angeles of all unions. By 1910, the IW was one of the last strong unions left in the city.

At 1 AM on September 30, 1910, a bomb exploded outside the L.A. Times building. The bomb was positioned next to several exterior gas lines, multiplying its explosive effect exponentially. Making matters worse, the L.A. Times had a nearby annex where thousands of gallons of highly flammable ink were stored. The bomb and ensuing fire devastated the building. Of the 115 people inside at the time of the explosion (mostly low-level workers trying to finish an extra edition of the paper overnight), 21 died. A majority of the deaths were from the fire. The bodies were horribly disfigured.

Two more bombs were discovered around the city. The first was outside of L.A. Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis’s house, the other was near the home of the secretary of a local business association. The bomb outside of Otis’s house was discovered before it detonated and the intended victims were able to get away, though detective attempted to defuse it before it blew up and barely escaped with their lives. The second bomb malfunctioned and police were able to recover it intact.

Although Los Angeles had a very capable police force for that period, its investigative methods were still primitive. LA Mayor George Alexander decided to hire William J. Burns, America’s leading private detective, to bring the bombers to justice.

Burns was a former Secret Service agent who launched his own detective agency. He had solved several high profile cases, including stopping an assassination attempt on the British ambassador. He was known for his integrity, and had been widely praised by labor leaders for unravelling a series of title frauds committed by business interests in the Pacific Northwest. Burns was already investigating a nationwide series of bombings similar to the L.A. Times attack for the National Erector Association and had an extensive network of contacts within America’s labor underworld.

After months of investigation (detailed in an article to come), Burns infiltrated a union hunting retreat undercover and was able to extract a drunken confession from J.J. McNamara. He learned that J.B. had planted the bombs on J.J.’s orders. He also identified Ortie McManigal as another bomber employed by the union.

When Burns had J.B. and McManigal arrested, they were found with a small arsenal and bombmaking material in their suitcases. Furthermore, several witnesses also identified J.B. near the scene of the L.A. Times bombing. Even more witnesses were able to identify the men as those who acquired the unique explosive mixture used in the bombings under false names. Faced with overwhelming evidence, McManigal was persuaded by Burns to make a full confession. Although he hadn’t been involved in the L.A. Times bombing, he knew all the details of the plan from the brothers. The bombs McManigal had set hadn’t killed or injured anyone.

The McNamaras did little to help their case after their arrest. J.B. stated to reporters as he was being extradited back to California that “This train will either be wrecked or blown up before we reach Los Angeles. I have eluded my captors enough to get word to my friends to see that we do not get to the coast alive.”1

The reaction from the American Left at the time was immediate and uniform: The McNamara brothers had been framed. McManigal had been bribed to give a false confession. The State Labor Federation of California sent a committee of “experts” down to the crime scene who issued a report saying that there was no evidence that explosives had been used at all. Rather, the “bombing” was actually an industrial accident stemming from a gas leak, cynically manipulated by business interests to discredit organized labor. Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs claimed that there had been bombs, but they had been set by business leaders as a false flag.2

To defend the McNamara brothers, the labor movement hired Clarence Darrow. Darrow was regarded as America’s most brilliant lawyer after he had successfully defended union boss “Big Bill” Haywood from murder charges in 1907. Haywood was an eccentric and bombastic figure who openly advocated for violence against the opponents of unions. The former governor of Idaho, who had declared martial law in an effort to stop union violence during his term, had been assassinated at his home using concealed explosives.

The bomber was eventually captured, but underwent a religious epiphany and named Haywood as the man who had ordered the killing. The bomber confessed to numerous other murders and detailed years of union violence. The evidence against Haywood was overwhelming and most legal journalists covering the trial thought he would be convicted, but after Darrow gave a lengthy and innovative closing argument (still reprinted today) that emphasized the larger social justice movement rather than the evidence, Haywood was acquitted. Prominent far-left lawyer Erskine Wood, a friend of Darrow, suggested mysteriously that Darrow had used “crooked methods” to secure the acquittal.3 The New York Times reporter at the trial said4 of Darrow’s closing:

He was a master of invective, vituperation, denunciative humor, pathos, and all the other arts of the orator, except argument. It was ostensibly a plea for the life of Haywood, but, in fact, it was an address, not to twelve jurors in front of him, but to his Socialist clientele…

After being acquitted, Haywood defected to the Soviet Union following an arrest for violating the Espionage Act of 1917. He died several years later due to a stroke brought on by alcoholism and diabetes.

Darrow demanded a fee of $50,000, the equivalent of $1.6 million today, to defend the McNamara brothers.5 He knew his clients were guilty before the trial began. United Press union organizer Ernest Stout reported on a meeting with Darrow in a memo, stating that “[Darrow] would not defend the McNamaras or McManigal because Burns had absolute proof of their guilt.”6 Although Darrow told Stout he wouldn’t take the case, he eventually agreed to defend the bombers.

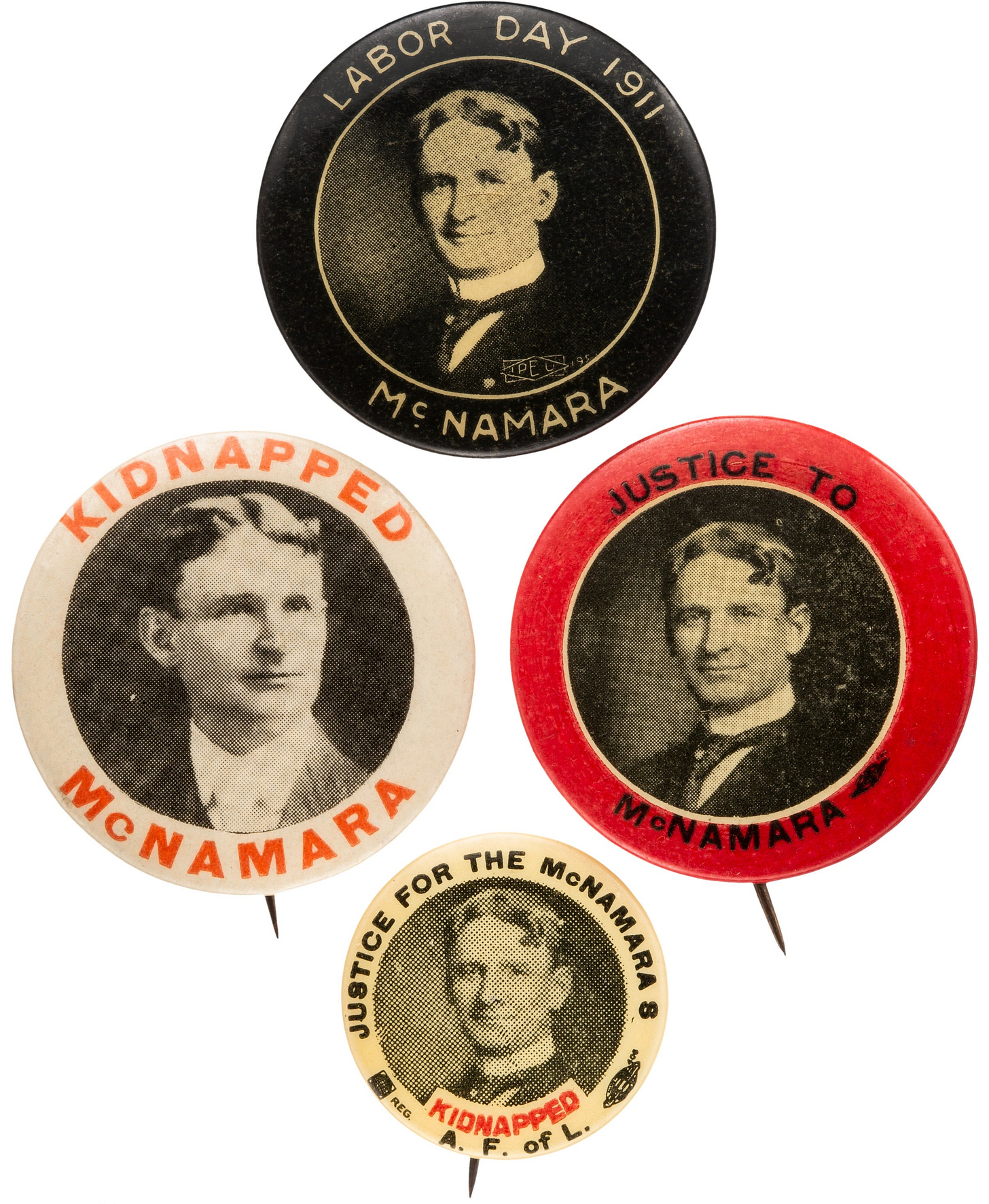

The labor movement embarked on a massive fundraising campaign to fuel the defense. American Federation of Labor (AFL) head Samuel Gompers appealed to every union to have each of its members contribute $0.25. A film was made, “J. J. McNamara—A Martyr to His Cause”, and sold about 50,000 tickets.7 A parade of about 35,000 union workers and labor activists marched through downtown LA to support the McNamaras’ innocence.8 Pins were also sold to raise money, centered around the idea that Burns had actually kidnapped the McNamaras during their arrest. The money was raised almost entirely through small donations from workers who didn’t have much, but believed Darrow and labor leaders when they said the McNamaras were framed.

Darrow hoped to raise $350,000 (the equivalent of $11,300,000 today) for the defense. He would need it, too, because defending clients who were so obviously guilty had costs. One of the witnesses, the man who sold the explosives used in the bombing to J.B., was approached by an agent of Darrow. The agent offered the witness a bribe if he would change his description of the man he had sold the explosives to. The agent told the witness that, if he didn’t accept the bribe, he would be murdered.9

In an entertaining episode, Darrow personally tried to bribe one of Burns’s top detectives to provide insider information on the case against the McNamaras.10 The detective accepted the bribe, secretly turned the money over to the prosecution, and then began (falsely) claiming to Darrow that various labor organizers and trusted confidants were actually spies for Burns. Darrow didn’t discover the deception until much later.

Darrow was constantly tailed by detectives. By this point, Burns and the prosecution were well aware that beneath Darrow’s “crusader for justice” persona was actually a deeply unethical and cynical activist who was willing to do anything get his clients off the hook, whether they were guilty or not. On September 1, police observed Darrow take an uncashed check to the office of San Francisco labor leader Olaf Tveitmoe. Tveitmoe deposited Darrow’s check, wrote a check of his own at a nearby bank, then cashed that check for $10,000 cash ($323,000 today).

The defense of the McNamaras got off to a bad start. Shortly after taking the case, Darrow had publicly endorsed the “gas leak” theory as to why the L.A. Times building suddenly blew up. Darrow paid thousands of dollars to construct a miniature model of the building, to be blown up with gas and prove that the source of the explosion couldn’t have been dynamite. Although the test was conducted several times, it actually showed that the explosion was almost certainly caused by dynamite.11

Making matters worse, a hotel clerk who could disprove J.B.’s alibi was located. Darrow’s agents had persuaded him to leave town without testifying. However, Burn’s detectives had managed to track down the clerk and convince him to return.

As the trial entered jury selection, Darrow was desperate. He knew his clients were guilty but he had staked his public reputation on their innocence. Furthermore, the real clients who were bankrolling him, Samuel Gompers and the AFL, appeared to have no idea that McNamaras were actually behind the bombing. As Darrow scrambled to salvage his case, the check he had given to Tvietmoe would take on enormous importance, both for the McNamaras and Darrow himself.

Unfortunately there isn’t enough space to include the entire story in one piece on Substack. You can find Part II of this article here.

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 110

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 127

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pt. 177

DARROW DENOUNCES HAWLEY AT BOISE; Calls State's Counsel Names and Sneers at Orchard's Religion in Closing Speech. IMPRESSES BIG AUDIENCE Says Haywood is Being Tried by an Alien Jury with Poisoned Minds. (1907, July 25), The New York Times, 7.

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 122

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 123

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 192

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 168

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 161

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 164

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 165

At some point in the near future you should put together a book debunking the commie propaganda we were taught. Obviously curate it on Substack first and get that subscription money

I first became suspicious of Darrow when I was reading a sympathetic biography of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, and he defended some obviously guilty violent anarchists at one point. It was actually a good read if you are able to see through the author's attempts to exonerate all these violent psychos and just assume everyone he talks about was guilty

Oh good. I'm loving these eviscerations of the prog Pantheon. Keep up the good work!