ACLU hero Clarence Darrow bribed juror to try to free bombers who killed 21 people (Part II)

Darrow v. The People

This article is a part of an ongoing series on the First Red Scare. The first part of the article can be found here. Although this article is free, the rest of the series will be paywalled. The two previous entries in this series were on the Sacco and Vanzetti case and a forgotten string of New York City church seizures by armed mobs of socialists in 1914. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work.

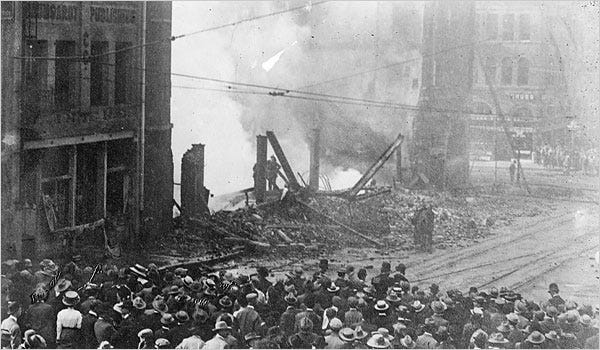

In 1910, famed civil rights lawyer Clarence Darrow had a serious problem on his hands. He had been hired to defend two labor leaders, the McNamara brothers, accused of blowing up the L.A. Times building and killing 21 innocent people. Darrow had accepted the case (and a $1.5 million inflation-adjusted fee) knowing full-well that the men were guilty.

Aside from his own private knowledge of their guilt, the publicly-known evidence against the men was overwhelming: there were dozens of witnesses placing one brother with the explosives and at the scene of the crime. An intrepid private detective, William J. Burns, had even managed to extract a drunken confession from the other brother. One of the brothers’ co-conspirators, a bomber frequently employed by the unions, had been captured and agreed to testify against the brothers in exchange for a deal.

Despite his knowledge of their guilt, Darrow embarked on a nationwide misinformation campaign to raise funds for their defense. He publicly proclaimed that the explosion at the L.A. Times building had actually been the result of a gas leak. This explanation was unconvincing on its own: two other identical bombs had been discovered at the homes of critics of labor unions that same night. The gas leak theory became even less convincing when demonstrations conducted by the defense, which were supposed to show that it couldn’t have been dynamite that caused the explosion, actually showed that it was almost certainly dynamite that caused it.

Most of the money for the case was raised from small donors: Union members and labor sympathizers who bought pins, pamphlets, or movie tickets in order to support the defense. Some unions, at the behest of American Federation of Labor head Samuel Gompers, implemented mandatory donations from workers to the defense fund. These people believed Darrow and other activists when they said that the McNamara brothers were innocent and had been framed by a business conspiracy.

Before the trial began, Darrow engaged in shady behavior to try and tip the scales of justice in his favor. A hotel clerk who saw one of the brothers check in at a Los Angeles hotel shortly before the bombing (disproving the brother’s alibi) was convinced by Darrow’s people to suddenly leave town without testifying. Private detectives working for Burns, who had been hired by the mayor of Los Angeles to bring the bombers to justice, managed to convince the witness to return.

This shady behavior on the part of Darrow and the defense team extended into outright criminality. One of the witnesses, a clerk who sold one of the brothers the unique explosive mixture used the bombing, was approached by an agent of the defense. The agent offered the witness a bribe to change his description of the man he sold the explosives to. The witness was then told that if he didn’t accept the bribe, he would be murdered.

Burns’s detectives and local police began shadowing Darrow and his agents. After a previous case where Darrow had managed to have a labor leader acquitted of murdering the former governor of Idaho, despite the overwhelming evidence against the labor leader, everyone knew that Darrow was willing to operate well outside the law. His behavior went beyond wanting his clients to have a fair trial. He wanted his clients to be acquitted of terrorist bombings because, as his later statements revealed, he supported terrorist bombings.

This barely-concealed support for terrorism among mainstream leftists, channeled through the L.A. Times bombing case, was not unique to Darrow. The left-leaning San Francisco Bulletin stated:

To the dispossessed in the rear of the courtroom, McNamara is a persecuted man, a martyr; Darrow is a hero; the District Attorney a very devil, the judge a monster. Among them are many potential bomb throwers. If McNamara’s life goes out on the scaffold at San Quentin, a white flare of hate will sweep out over the land. It will burn hottest where society’s outcasts gather in squalid rooms and make bombs, dreaming meanwhile of revolution. Perhaps even the judge wonders if there isn’t a better way.1

The trial would not come down to the evidence. The evidence only went one way: towards the McNamaras’ guilt. Instead, it would turn on who served on the jury. Could jurors be found who were OK with letting murders walk free? Bert Franklin was hired as Darrow’s chief “researcher” to handle investigation of potential jurors. Franklin was a former L.A. County Sherriff’s deputy and US Marshal who opened his own private detective agency.

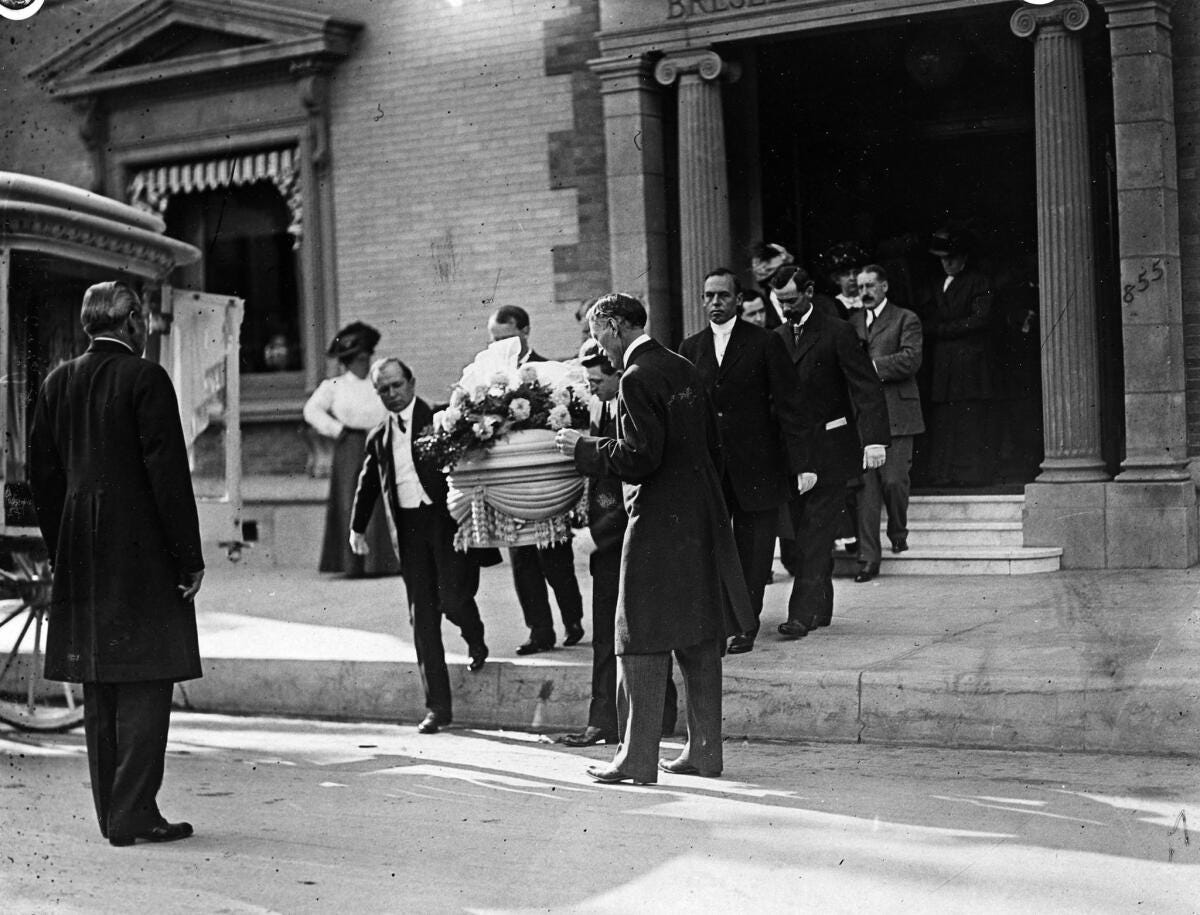

As the jury pool narrowed, Franklin targeted one of the potential jurors, Robert Bain. Bain was a proud 70 year old Civil War veteran who regularly played the drum in Memorial Day parades. Although he was a respected member of his community, after some bad investments Bain was desperate for cash. Franklin first approached Bain’s wife, offering to help the family pay off their mortgage if he would vote to acquit the McNamaras in the event he was selected as a juror.2

Bain’s wife begged Bain to accept the deal and, after some reluctance, he agreed. He refused to even look at the money after receiving it from Franklin, saying “After seventy years in which I served my country, my honor is gone.” Bain made the final list of jurors several days later.

Although the evidence-side of the case looked more and more hopeless for Darrow every day, the political side of the case was improving. Darrow added Job Harriman to the defense team. Harriman was a vocal critic of organized religion and member of the Socialist Party of America.

Although Los Angeles at the time was known as a conservative town, the openly socialist Harriman had surprised all political observers by coming in first during the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral primary. Harriman received an impressive 44% of the vote compared to incumbent mayor George Alexander’s 36%.

As Harriman worked for the defense, he was also campaigning against Alexander in the run-off election. Harriman often claimed that the McNamaras were framed as part of a conspiracy to prevent him from becoming mayor. It’s likely his overperformance in the primary was related to the mass labor organizing around the McNamaras’ defense. Darrow hoped to delay the trial long enough for Harriman to win the election, which would allow him to manipulate the judicial process through control of police and other city agencies.

Further bolstering the political side of Darrow’s case was that the District Attorney’s office in Indianapolis, where the McNamaras had hatched much of their bombing scheme, had been taken over by liberals. Although local police had seized enormous amounts of files and correspondence from the McNamaras and their associates, the Indianapolis District Attorney refused to hand them over to Los Angeles prosecutors to help make their case.3

They also refused to bring charges against union officials for the crimes detailed in the evidence. In fact, the Indianapolis District Attorney began the process of returning the gathered evidence to union officials, knowing that they would almost certainly destroy or alter it. It was only a direct appeal to President Taft by Otis, the L.A. Times publisher who was almost killed by a bomb set at his house by the McNamaras, that prompted federal officials to sweep in, secure the remaining documents, and share them with Los Angeles prosecutors.

As this was going on, jury selection continued. Darrow hoped to draw out the jury selection process as long as possible in order to ensure that the Socialists could win the upcoming election. There were frequent rumors, never proven one way or another, that Darrow began using large amounts of defense funds to support Harriman’s cash-strapped campaign.4

Bain, the man who Darrow had bribed first, managed to slip by the prosecution’s investigation and was selected by both the prosecution and the defense to serve as a juror in the upcoming case. Darrow turned the selection process for other jurors into a circus. He maintained that the case was not about a bombing or murder, but rather the larger “war” between labor and capital and the national movement for social justice. His asked pointed questions about prospective jurors’ religious and political views. It was a performance for the press and an attempt to poison the well before the evidence against his clients was discussed during trial.

On November 7, 1911, one of J.J. McNamara’s best friends, who had participated in several union bombing plots, agreed to testify against the brothers.5 Although the case was bad before, the evidence gathered by Burns and his detectives was simply bulletproof. It gradually became more and more impossible for anyone but the most hopelessly indoctrinated or naïve to accept the McNamaras’ innocence. Everyone involved with the McNamaras knew that they would be going down for something, somewhere.

Darrow began exploring options for a plea deal. Business leaders had had enough of terrorist bombings, they wanted blood. However, they also wanted to defeat Harriman in the election and prevent a socialist from becoming mayor. Everyone knew that a guilty plea would complete destroy Harriman’s election chances since he had staked so much on the brothers’ innocence, and publicly claimed that the bombing was actually a conspiracy by big business. The McNameras confessing would totally discredit the labor movement both in Los Angeles and the rest of the country. Harriman was kept in the dark about the plan to throw him under the bus.

Far left journalist Lincoln Steffens, Darrow’s friend, acted as an intermediary between the defense and business interests, hoping to work out a deal that would at least spare J.J., against whom the evidence was more circumstantial. Sweetening the pot was the offer that the AFL and other Los Angeles unions would end their ongoing and widening strikes in the area exchange for light sentences for the brothers.

The prosecution wasn’t up for a deal that didn’t involve jail for both men. They had both brothers dead to rights for the bombing. Law enforcement was tired of the brazen criminality from these labor mafia organizations. It was only a matter of time before another mass casualty event occurred. The brothers themselves were also unwilling to accept a deal that would save one brother by condemning the other.

Furthermore, they had dedicated their whole lives to the labor movement. Although LA was hostile to unions, and would only be more hostile in the event of a guilty plea, the McNamaras knew that admitting to the bombing would devastate the very powerful San Francisco unions that they frequently worked with. It was worth it for them to risk a trial. Even if they were found guilty, they could always create a similar “falsely convicted” narrative like those built for other (definitely guilty) heroes of the far left around that time. Who knows? They might even be let off, eventually.

As Darrow prepared for trial, Franklin set his sights on another prospective juror: George Lockwood, a former law enforcement official who Franklin had worked with when Franklin was a deputy sheriff. Lockwood was living in semi-retirement on his ranch on the outskirts of town when Franklin approached him on November 14.6 Lockwood was outraged by the suggestion that he would take a bribe and immediately reported the offer to a friend at the L.A. District Attorney’s office. Rather than take immediate action, the District Attorney, John D. Fredericks, told Lockwood to play along and accept the money when Franklin inevitably approached him again.

When Lockwood’s name was drawn as one of the final candidates to be considered for jury duty, Franklin showed back up at Lockwood’s ranch. He promised Lockwood $4,000 (the equivalent of $130,000 today) if he would vote to acquit the McNamaras if he ended up on the jury. There would be an initial payment of $500 and then the rest of the money would be delivered after the trial.

Following his instructions from the District Attorney, Lockwood demanded that the remainder of the money be held by a mutual friend to ensure that he would be paid after trial. They agreed to meet in downtown LA to make the handoff.

On November 28, 1911, Lockwood, Franklin, and the intermediary met at the predetermined spot and exchange the money. The $4,000 was all there as agreed. However, Franklin soon noticed that they were being watched: at least 6 LAPD detectives were surveying the scene. Not realizing that he had been set up yet, Franklin told the men to start walking down the street. As they began to move away from the detectives, Franklin spotted Clarence Darrow himself walking straight towards the group.7

Franklin said “Wait a minute, I want to speak to this man,” as he approached Darrow, but before they could say anything to each other they were intercepted by LAPD Detective Samuel Browne. Browne separated the men, who were only a few feet apart, and placed Franklin under arrest. Darrow was allowed to leave the scene and his presence wasn’t widely known until weeks after the arrest.

The bribery charges made national headlines. Darrow quietly bailed out Franklin using $10,000 cash (about $323,000 today), a large portion of the remaining defense funds. He took pains to conceal the fact that he had been spotted at the scene. Prosecutors had made no mention of it in the press. They had plans. Darrow publicly denied that any defense funds had gone towards bribery, a shameless lie.8 Although he had long considered the case against the McNamaras to be hopeless, Darrow now faced the prospect of charges of his own.

In late December, Darrow drunkenly visited one of his mistresses and put a revolver on her table. “Molly,” he said, “I’m going to kill myself. They’re going to indict me for bribery in the McNamara case. I can’t stand the disgrace.” He then began to sob.9

Although Darrow would be talked out of suicide, his upcoming trials for bribery would be the darkest points of his life. While the matter has been largely airbrushed out of his legacy today, his statements and tactics during his bribery trial more clearly sketch Darrow as a “civil rights leader” than any of the influential cases in which he was representing others.

Unfortunately there isn’t enough space to include the entire story in one piece on Substack. You can find Part III of this article here.

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 194

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 182

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 198

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 203

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 202

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 231

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 237

CHARGES OF BRIBERY IN M'NAMARA TRIAL; Four Thousand Dollars Found on Men Accused of an Attempt to Influence Jury. (1911, November 29) The New York Times, 1.

The People v. Clarence Darrow, pg. 4

It still blows my mind that this stuff was happening 100+ years ago. The rot has been for far longer than I initially thought.

I was always taught that the red scare was unfounded. If anything, I am constantly learning that my own education was “red-washed” -- communist atrocities both here and abroad either minimized or literally taken out of history books entirely. We did learn about the scopes monkey trial in depth.