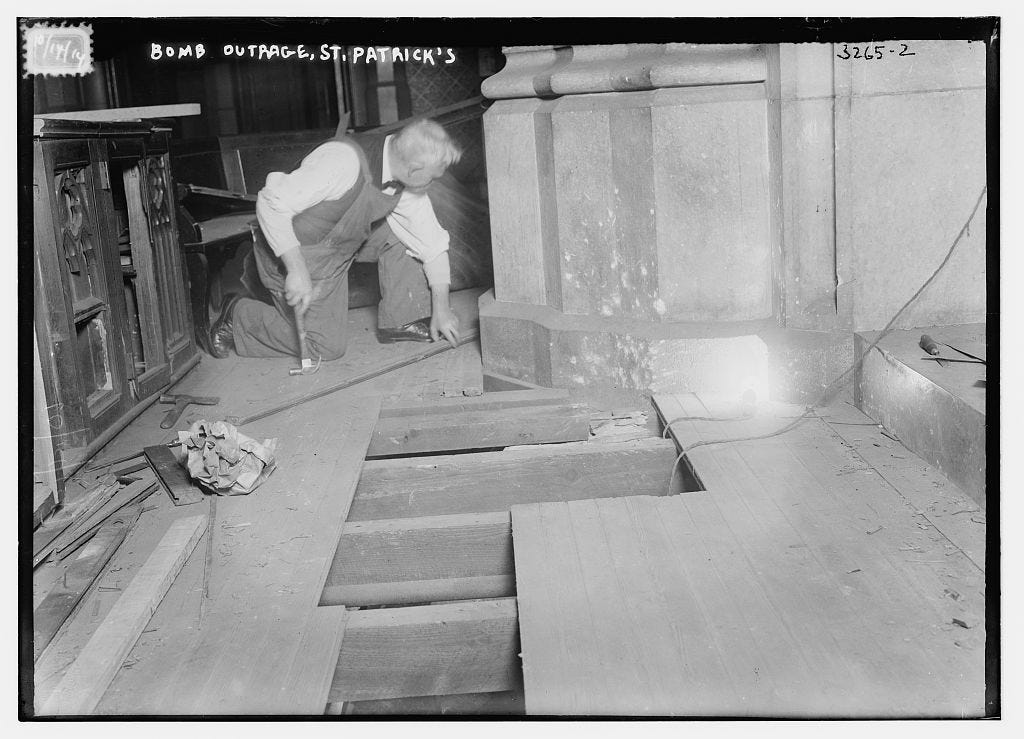

Anarchists almost blew up St. Patrick's Cathedral in 1915

Detectives snuff out the lit fuse after capturing bomber in the act

On October 13, 1914 a bomb blew up in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. The bombing coincided with the anniversary of the 1909 execution of Francisco Ferrer, a Spanish anarchist, who had been arrested and convicted for his organizing role in a period of unrest and rioting today known as Barcelona’s Tragic Week. The unrest was triggered by a renewal of public conscription for the Spanish military’s extended intervention in Morocco. More than 170 people were killed in the ensuing confrontations, which featured open warfare between police and an alliance of anarchists and socialists.

Although America had nothing to do with Ferrer’s arrest or execution, anarchists across the globe had pledged revenge against the Catholic Church, which had long favored Spain’s conservative establishment.

The bomb did little damage to the cathedral and produced no casualties, but it did generate substantial alarm in New York City. At the time of the bombing, the cathedral was packed with parishioners. A piece of shrapnel had grazed the head of young boy. This alarm was amplified when word came that a second bomb had detonated in front of the rectory at St. Alphonsus Church later that evening. One priest was injured in that blast.

St. Alphonsus had been the site of an earlier riot by communist-backed International Workers of the World (IWW) union members. Local IWW leader Frank Tannenbaum had led a series of large and rowdy “protests” in which mobs of homeless and unemployed, directed by IWW organizers, would swarm local churches and demand food and shelter. It was a shakedown that most churches complied with. On March 5, 1914, Tannenbaum led a 200-strong mob to St. Alphonsus, only to be arrested by police1 for inciting a riot. He was sentenced to just one year in jail.

As a bit of trivia, after Tannenbaum was released from prison he become an influential history and criminology professor at Columbia University and helped create the Farm Security Administration, a short-lived New Deal propaganda agency that advocated for farm collectivization.

The anarchist bombing network in New York City suffered a major setback on July 4, 1914. Two members of the Lettish (Latvian) section of the Anarchist Red Cross, Charles Berg and Carl Hanson, along with IWW member Arthur Caron, gathered dynamite they had obtained from Russia in an apartment on Lexington Avenue owned by an editor of infamous anarchist radical Emma Goldman’s magazine.

Although nominally the anarchists and communist IWW members had divergent interests, functionally the two left-wing radical groups were indistinguishable. There was enormous overlap between these networks. NYPD Bomb Squad lead inspector Tom Tunney said “If you scratched an anarchist, you found an IWW underneath.”

According to prominent anarchist Alexander Berkman (who claimed to have been uninvolved in any plot despite meeting with the bombers several times), the men planned to use the explosives to kill J.D. Rockefeller2 and his son. However, for reasons unknown, the bomb they were assembling detonated prematurely. All three bombers and an uninvolved neighbor were killed in the blast. Dozens more were injured.

Bombings continued after the twin October 13, 1914 attacks on St. Patrick’s cathedral and St. Alphonsus. On November 11, the Bronx courthouse was bombed. On November 14, a bomb was discovered beneath the seat of Magistrate Campbell, the judge who had sentenced Tannenbaum and had a reputation for taking a hard line against terrorism. Campbell had been about to sit down before an attentive officer had warned him of the device and disarmed it.

Although the perpetrators of the successful bombings were never identified, they were suspected to be anarchists. The then brand-new NYPD bomb squad set their sights on the Bresci Circle, a 600-strong group of anarchists that regularly met in Harlem. The group had been named after Gaetano Bresci, the anarchist who had assassinated King Umberto I of Italy in 1900. Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman regularly spoke at Bresci Circle meetings.

The youngest member of the NYPD Bomb Squad was Amedeo Polignani. Because he could speak Italian and was known for his uncommon nerve under pressure, he was ordered to infiltrate the Bresci Circle and discover the perpetrators of the church bombings. After months of attending meetings, Polignani managed to gain the trust of the most radical members of the group, swearing an oath on the hilt of a dagger. He was soon introduced to young anarchists Frank Abarno and Carmine Carbone. Carbone was missing several of his fingers, apparently lost while building bombs.