Elon Musk's Reddit Retard Rebellion illustrates the danger of political inexperience in an existential struggle

Everything's ending, it's time to wake up

I read a lot about the Russian Revolution and Russian Civil War. It’s often hard to read new books about these topics because the biggest lesson you’ll learn from extensive study of the period is that all the tragedy was not inevitable.

Everyone identifies roughly the same factors that led to Bolshevik victory. They weren’t hard to identify, people noticed them at the time. The Bolsheviks were not popular, they were not particularly competent, and they made plenty of mistakes that should have been fatal. On a military level, the Bolsheviks were inferior to the Whites (who secured the loyalty of far more former Russian military officers and specialists) for most of the war despite the Bolsheviks’ great advantage in raw numbers and material.

However, the various White armies formed to oppose the Bolshevik coup suffered from a profound political retardation. They could not agree on what they wanted, who was in charge, how they should act, or that they even needed to have “a side.” It is truly sobering to realize just how many unforced errors the Whites, who could and should have won, made as the Bolshevik freight train hurtled towards them.

One of the main contributors to the Whites’ defeat was political inexperience. This concept is frequently mentioned in Peter Kenez’s excellent books Red Attack, White Resistance and its sequel Red Advance, White Defeat, which are the best military histories of the Russian Civil War, as well as The White Generals by Richard Luckett, which I think is the best overall summary of the conflict (but not the Revolution more generally, if you want a good survey of that I’d recommend The Russian Revolution: A New History by Sean McMeekin). Although I was already planning a different article on this exact topic, Elon Musk’s recent very public breaks with President Trump offer a good launching point to explore this concept.

White leadership primarily consisted of military leaders who brought with them the assumptions of a military hierarchy and Russian society that no longer existed. They were ruthless when a light touch was required, passive before events that demanded a response, tolerant of obvious liabilities and needlessly hostile to potential allies, stubborn about all the wrong things, demanding of the impossible, and just fundamentally unable to make something work.

The challenge wasn’t that the leaders of the White Army weren’t brave or smart or good or right, it was that they literally didn’t know what they were doing. They had never been in that situation before and did not know how to navigate it. Luckett writes:

“[The White Army’s] failure is, to an extent, understandable: the business of revolutionaries is revolution, but the business of counter-revolutionaries is seldom counter-revolution. Revolutionaries are born into their condition. Counter-revolutionaries have it thrust upon them.”

In contrast to the counter-revolutionary Whites, the revolutionary Bolsheviks had decades of experience in political and diplomatic matters owing to the nature of the radical community. They were very adept at working within parliamentary organizations and easily outmaneuvered their naïve and inexperienced leftist rivals during the tumultuous months of the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks made plenty of mistakes, but it was their experience and discipline that allowed them to recover. Because they were so used to operating outside of the law and the norms of society, they could much more easily adapt to the state of chaos that the former Russian Empire had fallen under.

General Wrangel wrote that his first reaction to learning of the Czar’s abdication was “This is the end of everything. This is anarchy.” Wrangel was, as usual, uncommonly perceptive.

The Russian Revolution should not be understood as a popular uprising with a predetermined outcome, but rather a prolonged state of anarchy that eventually transformed into a new order steered by a small group of unpopular radicals who just played their cards right. Not only was the government overthrown, but everything people “knew” started to shift.

Dietrich Neufeld (aka Dirk Gora, he had to use a pseudonym due to the threat of assassination), a Dutch Mennonite living in Southern Ukraine, where the anarchist bands of Nestor Makhno launched a mass robbery and ethnic cleansing campaign targeting non-ethnic Ukrainians, wrote in his book A Russian Dance of Death that:

The Ukrainian peasant has become rebellious in consequence of a constant change of regime. Is it not true that for two years he has had to endure, with almost every new moon, a new government? After this, and very soon, there will not be an administration which can easily gain his respect.

Certain moral conceptions, which should underlie any form of state, have been overthrown.

Not a lot of people are prepared to deal with a society where “stealing is wrong” is no longer an assumption that most people carry with them, yet that’s exactly the situation that Neufeld and millions of others found themselves in. Czar Nicholas II was bewildered when he received petitions from many prominent members of society to pardon the men who had murdered the folk-healer Rasputin, because they believed (incorrectly on all counts) that Rasputin was a German spy, exercised an enormous amount of control over the royal family, and possessed evil wizard powers. Didn’t they know that murder was wrong? Not anymore. Things were starting to come apart.

The Bolsheviks, who had operated as a clandestine political party and quasi-terrorist group for more than a decade, were suited for this environment in a way that the various anti-Bolshevik leaders were not. They understood the importance of vision, ruthlessness, and organization, things that many White leaders took for granted because they had always been able to rely on broader society to provide all of these things. Because the Bolsheviks had existed outside of the law and social order for so long, they were more capable of acting as a law and social order onto themselves.

Especially in the early days of the White Army, political inexperience served as a huge obstacle to the Whites’ efforts. Volunteer Army leaders like Alexeiev and Denikin, whose pre-Revolution experience was almost solely in the realm of military operations, made political mistake after political mistake. Their public position was that the Bolsheviks must be stopped so that Russia could reenter the war against Germany, even though the war had become extremely unpopular and they were at the time dependent on the protection that local German garrisons provided to their flanks, on top of huge shipments of critical German arms and ammunition that were being passed to them through Pyotr Krasnov’s Don Cossack government. It would have probably been better if they had said nothing about this topic at all, since their sympathies should have been and were obvious to outside observers.

Krasnov, a charismatic adventurer with limited political experience, made himself too conspicuous an ally of Germany, which at the time was losing World War I. Although Germany did provide Krasnov’s Don Army with desperately needed weapons and ammunition, his unnecessary and flamboyant public pronouncements of his German orientation created numerous diplomatic headaches for anti-Bolshevik forces in the region when dealing with the Allies, who were still toying with the idea that Bolshevik Russia might be persuaded to re-enter the war against Germany. Krasnov probably could have gotten what he wanted without closing those doors for himself, but did not know how or why he should do so.

This inexperience extended down the ranks. The former Russian military officers who composed the core of the White Army simply weren’t used to dealing with the political and diplomatic considerations that they were presented with. There was little sense of where the public mood was, or of what was and wasn’t possible or effective.

Denikin frequently complained that a large swath of his men were ardent monarchists, even though the monarchy was very unpopular at the time and there was no clear successor to Czar Nicholas II, who had been imprisoned and murdered in secret by the Bolsheviks in July 1918. Whatever the theoretical arguments for monarchy may have been, how could the monarchy actually be restored in practical terms at that moment? It was impossible, but Monarchist officers weren’t really thinking about that and didn’t feel they had to because they could control their territory through force of arms. This control proved to be far more tenuous than they expected without the support or at least indulgence of the public, which they gradually lost despite general opposition to the Bolsheviks.

Kenez theorized that the way Whites handled diplomatic and political disagreements was most similar to the way that a gossip or rumor campaign would be conducted at a military academy or a bureaucratic power-struggle would proceed in the pre-Revolution military. These struggles presume that participants have similar backgrounds and a similar interest in the military’s continued existence. If you “lost” such a struggle, the worst thing that might happen to you is being transferred to an undesirable post or perhaps forcibly retired early. These were matters that the Whites all had extensive experience in, but that experience proved to be mostly useless in the realm of real-world politics or civil war, where the existence of institutions and norms they had once relied upon was not a given and losing meant having your country destroyed and maybe ending up in front of a firing squad.

Many groups other than military officers were experiencing these kind of growing pains as Imperial society collapsed around them during the Revolutionary period. Historian Richard Pipes writes in The Russian Revolution that:

… [N]early everything the peasant learned in his familiar environment proved to be useless and sometimes positively harmful when applied elsewhere. Living in a small community, the Russian peasant was unequipped for the transition to a complex society, composed of individuals rather than households and regulated by impersonal relations, into which he would be thrust by the upheavals of the twentieth century.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the most successful anti-Bolshevik general of the period, Marshal Mannerheim of Finland, had a background as a diplomat, explorer, and spy on top of his successful military career. He knew how to talk to people and how and when to make a deal.

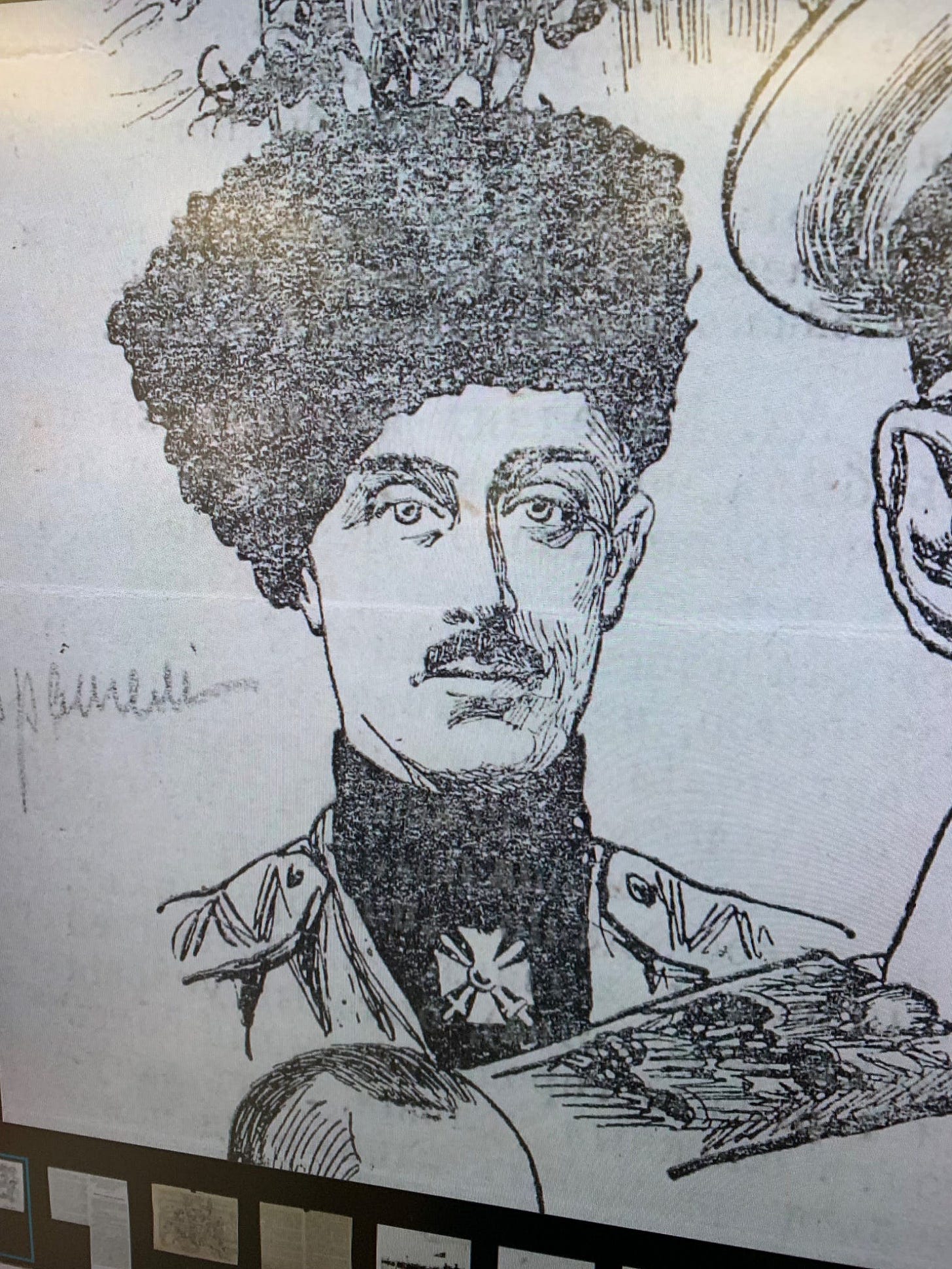

General Wrangel’s remarkable (though sadly not decisive) success probably stemmed from his previous experience commanding Cossack troops and being stationed in Poland before the Civil War. He could navigate the complex social dynamics of the period in a way that many of his peers could not. Even as a young officer Wrangel was considered a social butterfly while the bookish and insecure Denikin had trouble making friends and relating to his peers. This might not have been an issue in an organized military force fighting a conventional conflict with a rival power but became a huge one when Denikin was forced to act as both head of state and commander-in-chief of a political army during a civil war.

When the Volunteer Army, which mostly consisted of non-Cossack refugees, initially arrived in Don Cossack territory, one of their only local allies was General Kaledin. Kaledin was a former military officer who had declared himself the dictator of the region to stop a Bolshevik uprising during the October Revolution. This was later ratified by the local Cossack government. Although Kaledin was nominally in political control, his power and resources were very limited and required constant negotiation with other parts of Cossack society, which had also been plunged into a state of anarchy. This meant he often had to say “No” to requests from the Volunteers.

Although Alexeiev was frustrated by this, he tried to maintain good relations with Kaledin, who was pretty much the only major local figure who tolerated his men. Without Kaledin, it is certain that local Bolsheviks would stage an uprising that was also certain to be successful. However, one of Alexeiev’s top lieutenants took Kaledin’s constant refusals as a sign that Kaledin needed to be removed and replaced with a Volunteer government. He began planning a coup against Kaledin without any authorization from Alexeiev.

This Volunteer coup would have had no hope of success: Although Kaledin’s popularity waxed and waned, the Volunteers were always far less popular than Kaledin was with the Don Cossacks. As outsiders, they would have had no base of power or public support to draw from. In fact, staging a coup against the locally elected leader would have only seemed to confirm Bolshevik propaganda that reactionary military officers were really just trying to overthrow the will of the people. A coup government wouldn’t have lasted more than a few days.

The fact that a Volunteer coup against Kaledin was unnecessary and that success was impossible notwithstanding, the officer behind this effort also just had no idea how to plan a coup or conduct any kind of clandestine activity. He was a military officer, that’s all he’d ever done. As soon as he tried to do something else, he floundered because he had no idea what he was doing. Word of the planned coup quickly spread and it greatly embarrassed Alexeiev, who had to reassure Kaledin that he wasn’t planning anything, he merely had limited control over his top subordinates, who also might be morons. It made the Volunteers look like an unstable and potentially treacherous partner.

The most insidious aspect of the coup attempt was that it was directed at one of the only officials who bothered to engage with the Volunteers. They knew Kaledin existed and that made him a target for some ill-formed conspiracy. This created heavy disincentives to interact with the Volunteers. Many former Russian officials and prominent members of society thought it was not worth the trouble to negotiate with such an immature and unstable organization, preferring to wait and see what new potential partners might emerge from the chaos.

Boris Savinkov, a former radical socialist who had become an unlikely ally of the military during the chaotic days of the Provisional Government that preceded the Russian Revolution, travelled to Volunteer Army territory shortly after their victorious Ice March (details of that here) eventually allowed them to settle into a more stable base in the Kuban. Savinkov was one of the few high-ranking officials in the Provisional Government who had supported General Kornilov, one of the founders of the Volunteer Army, during the Kornilov Affair (you can find a rundown of that complex sequence of events here). Although Kornilov had been killed in battle, Savinkov was still a hardcore anti-Bolshevik and approached Denikin and Alexeiev to see if they could unify their efforts.

Savinkov had previously proven himself to be a reliable opponent of the Bolsheviks, offered some degree of legitimacy as a member of the recently-deposed Provisional Government, maintained an extensive network of spies and supporters in Bolshevik-controlled Moscow and Petrograd (which the conservative military officers of the Volunteers did not have), and was trusted by the Allied governments (they would eventually equip Savinkov with hundreds of millions of dollars for an anti-Bolshevik coup attempt) who were at the time skeptical of the Volunteer Army. Despite this, Alexeiev and Denikin gave him the cold shoulder. He was warned that he would be murdered if he stayed in Volunteer territory and departed soon afterwards to try to organize anti-Bolshevik forces in another part of the country.

The pair actually had good reasons to be hostile to Savinkov. They thought he was a piece of shit, and he was. After all, Savinkov was not only a morphine addict and a former radical leftist, he was also a murderer. He had been convicted for his role in several terrorist bombings targeting officials of the old Imperial government but was pardoned by the Provisional government as a snub to the old regime. Despite this horrible past, he was exactly the sort of character who the Volunteers could have and probably should have made something work with. They needed the things he had to offer and, having failed to make an agreement, no one benefitted.

A similar failure could be found in the Whites’ early treatment of the newly independent nation of Georgia. Georgia, like many parts of the former Russian Empire, had declared its independence after the legitimate Russian government had collapsed. Despite being nominally independent, the Georgian government seemed eager to make a deal with the Volunteers. Not only did they not have much of a military of their own, but also the Georgian government was dominated by Mensheviks, a leftist party that had split away from the Bolsheviks several decades prior. Georgian Mensheviks knew that if the Bolsheviks were triumphant in Russia, an invasion and conquest of Georgia would follow soon afterwards.

Early diplomatic contact between the Volunteer Army’s envoy and the commander of Georgian military forces went surprisingly well. The two men hit it off immediately and developed plans to collaborate against the Bolsheviks. As a gesture of good will, the Georgians gifted the Volunteers an armored train (the first to come into the Volunteers’ possession) before sending their own diplomatic delegation to Volunteer territory to try to work out some kind of deal.

The Volunteers didn’t even bother to meet the Georgians at the train station. When the Georgian delegation eventually made their way to Volunteer headquarters, Denikin, Alexeiev, and the other assembled staff laid into them for their bad behavior before the Revolution. They refused to acknowledge Georgia’s nominal independence, in other words to acknowledge that the delegation even had the ability to negotiate, and maintained an atmosphere of total hostility. Nothing of substance was discussed, nothing was gained from negotiations. The Volunteers even made dubious criticism of the armored train the Georgians had just gifted them. The Georgians walked away from the meeting thinking there was no way they could ever make anything work with the Volunteers.

The funny thing is, the Volunteers’ hostility was mostly justified. The Georgian Mensheviks were extremely belligerent towards both the Czarist regime and the Provisional Government. This belligerence contributed to the collapse of both of these governments and the rise of the Bolsheviks. From the perspective of the Volunteers, the Georgians bore a large portion of responsibility for the predicament they now found themselves in. There was a lot of well-earned bad blood between the two parties. Furthermore, the Volunteers already had to deal with a clown-car’s worth of secessionist groups with claims of wildly varying validity. It was easy for the Volunteers to dismiss tiny Georgia, which had no ability to defend itself and seemingly no ability to challenge the Volunteers.

Even still, however justified the hostility may have been, it was not productive at all. By blowing up the negotiations, the Volunteers failed to make any kind of deal with their southern neighbor, which had shown signs that it was willing to work with them and which the Volunteers could not overthrow or occupy on their own.

Georgia could have been a very useful source of supplies or international support. Although it was a weak government, it was a government that actually had a real organization and buy-in from the people it claimed to represent. This is more than you could say for the Whites in most areas they controlled. The Whites, with little experience or interest in politics, only ever developed primitive political bodies and civil administration, leading to total disorganization behind the lines (this would prove to be a fatal flaw during Denikin’s March on Moscow). The Volunteers were fighting a multi-front war and still turned a potential ally, or at least a potential neutral party, into an enemy.

After negotiations failed, the Georgian government funded guerilla bands that caused havoc in the Whites’ rear as the main White force was occupied farther north on the frontlines facing the Bolsheviks. They thought (incorrectly but understandably) that a total White victory might be as bad for them as a total Bolshevik victory. The two sides couldn’t make a deal and so both ended up losing big. The Southern grouping of the Whites would be defeated in 1920 and Georgia would be invaded and conquered by the Bolsheviks in 1921.

I think the mistake stemmed from political inexperience. The Volunteers were probably “right” but that ended up not mattering as much as they thought it would. “Correct but not productive” is not something they usually had to grapple with in a diplomatic context. Instead of keeping the door open for some kind of future deal, Denikin and Alexeiev slammed it shut permanently. They weren’t used to navigating these complex political dynamics and so preferred not to navigate them at all. This is not a viable strategy in an inherently political conflict like a civil war. Despite the Whites’ huge military successes, lots of stunning bravery against overwhelming odds, their political failures ended up sinking them.

This dysfunction was most obvious in times of crisis. One of the biggest political challenges for the Whites came from the split between Denikin and Wrangel. This dispute is covered extensively in Wrangel’s memoirs, I won’t recount it here. Although the various public and not-public direct clashes between Wrangel and Denikin are covered in that book, the aspect of the feud I think is most interesting came from outside of the parties.

There were many people outside of Denikin and Wrangel who actively tried to engineer their dispute, nominally to “help” whichever leader they supported. Denikin’s chief-of-staff, Romanovsky, seems to have deliberately withheld supplies and reinforcements from Wrangel and tried to have many of Wrangel’s associates set up on false charges. He likely concealed these efforts from Denikin.

Wrangel’s own supporters, against Wrangel’s wishes, also attempted to force a break between the pair. They leaked internal reports criticizing Denikin’s strategy and proposed that Wrangel take Denikin’s place at the top of the White Army. One officer even staged a mutiny and demanded that Denikin resign and accept Wrangel as his replacement. Denikin assumed, incorrectly, that all of these efforts were being directed by Wrangel and retaliated further.

Wrangel, for his part, understood the political situation well. Despite his obvious issues with Denikin, Wrangel publicly condemned all efforts to subvert Denikin’s authority and stated, correctly, that coups and mutinies were not how succession should happen in a military organization. In times of war you have to obey your commanders’ orders. That’s how hierarchical organizations work. If everyone is off doing their own thing, it becomes impossible to get anything done at the scale required for success. Public infighting in this way for any reason is inherently harmful. Rather than acting like members of an army, many White leaders were trying to act like political operatives or spies and doing a very bad job of that.

Wrangel’s pleas for good order fell on deaf ears as the White Army’s front collapsed, however, and the break between Wrangel and Denikin eventually became irreparable. Wrangel was exiled under pain of death by Denikin, who himself fled Russia soon afterwards. The factions had engaged in so much subterfuge only for both to lose. No one knew what they were doing. When they tried to do things, they ended up making the situation worse.

Finally, there was a total lack of discipline in the areas the Whites controlled: Corruption, speculation, and extrajudicial killing were all commonplace. On one hand, this is understandable: The police, the courts, and the legal system in general had collapsed. It was difficult to find anyone to step up and do basic low-level law enforcement and the Whites preferred not to tackle such a complicated problem.

Denikin tolerated enormous unauthorized requisitions of supplies (which disrupted the flow of critical arms, ammunition, and fuel to various sections of the front), along with various outrages that alienated the public, by figures like General May-Mayevsky, an alcoholic and drug addict whose chief aide proved to be a Bolshevik agent (which many warned him about because the aide’s brother was known to be a high-level Bolshevik secret police officer, though these warnings were ignored). These kind of lapses were commonplace. Denikin worried that if he started imposing basic standards of behavior he would have very few soldiers or commanders left.

It was only after May-Mayevsky began to lose battles that Denikin worked up the courage to fire him and replace him with Wrangel. By then, the damage had already been done and it was difficult to repair the Whites’ reputation in the areas that May-Mayevsky’s bad behavior had thrown into disarray.

It’s not like this problem was impossible to solve. Wrangel was notorious for holding field court martials for criminals, civilian or military. This strict discipline made him more, not less, popular with his men and the public. I’ve read a lot of memoirs about the Russian Civil War, and the anecdote that appears the most in these memoirs is Wrangel deciding to publicly try and hang a railroad official who accepted a bribe to transport merchants’ goods rather than civilian refugees away from an area of the front that was being evacuated. After the trial and public execution, the evacuation proceeded more quickly than expected.

The story is well known probably because this kind of decisive action against wrongdoing was so rare in the areas that Whites controlled. Wrangel didn’t walk up to the railroad worker and shoot him or engage in some complex maneuvering against him. Wrangel just did what a military leader was supposed to do during a national emergency, no more no less. He was the law, and a real law that most people could and would accept as legitimate.

None of this is to say that political mistakes were exclusively the realm of conservative military officers during the Russian Civil War. A great deal could be written about the naïve and dysfunctional socialist and liberal governments that populated Siberia and crippled anti-Bolshevik military efforts in that region (which should have served as the Whites’ strongest base) or the malignant chorus of exiled Russian public figures abroad who tried to undermine the Whites’ international support at every turn.

Inexperienced people were trying to figure out their roles on the fly and the results were less than spectacular. It should not be surprising that it was difficult to manage political disagreements without seasoned politicians, to conduct diplomacy without trained diplomats, and to manage states without statesmen.

I could go on (I had planned to talk about Denikin adopting an unnecessarily harsh view of Russian officers who had served in various anti-Bolshevik Ukrainian formations and his naïve banning of former Imperial secret police officers from his already dysfunctional government but this is running a little long), but I think Elon Musk’s recent bizarre implosion demonstrates a similar failure to adapt to unfamiliar circumstances.

Musk entered the world of conservative politics very late. He inexplicably voted for Biden in 2020, only publicly shifting his party affiliation after his child was trans-ed and it seemed clear that a victorious Kamala administration would throw him in jail and take his money. Musk was very open about not being particularly conservative, which seemed fine because he brought hundreds of millions of dollars in political donations and a great easing of censorship of conservatives on Twitter to the table. I think these contributions played a decisive role in the 2024 election and Musk deserves an enormous amount of praise for them.

Trump made good faith efforts to incorporate Musk into his administration, appointing him to lead the new Department of Government Efficiency and take an uncommonly prominent role at public events. Musk repaid Trump’s trust with a series of embarrassing and unnecessary blunders, popping a meme Roman salute at Trump’s inauguration (everyone can stop pretending that this isn’t what happened now), giving speeches where he was obviously under the influence of drugs, and allowing his bizarre paternity scandals to creep into the public eye. This is not how someone who is legitimately “in charge” is supposed to act and everyone knows it.

Musk was obviously not used to dealing with the world of politics and government, his views about both seem, frankly, stupid. He supported liberals for most of his life, even though liberals harmed his child and tried to take his money before he had even done anything to them. Musk then supported Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s obviously doomed primary effort to unseat President Trump. Musk dramatically underdelivered his promised cuts to government spending and fumbled badly during the public feuds he started, such as the Christmas H1B fiasco. Musk was not a good politician, bureaucrat, or administrator—roles that he had asked to take on as a reward for his contributions during the election.

Instead of trying to figure out what had gone wrong or reevaluate his position, Musk chose to lash out and behave even more erratically. Rumors (which I believe) claim that he physically attacked Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent after a heated debate in the White House and was punched in the face for his trouble. I find it very difficult to believe that Musk wasn’t on drugs when this happened.

This was all obviously not appropriate behavior for someone occupying a high position. It undermines the legitimacy of American institutions, which rely on public trust. Musk was politely shown the door. However, Musk couldn’t accept defeat quietly and embarked on a bizarre series of tirades where he claimed that Trump should be impeached and replaced with Vance, that Musk should form a new party to represent the imagined “80% in the center,” and then that Trump was a pedophile.

All of these claims demonstrate a profound lack of fluency in politics. What Musk did was not just stupid, it had no chance of success. It was a pure waste. If he wanted to have a break with Trump (a very dumb decision, but OK), there were many better ways he could have done it. Yes, Musk is likely a drug addict, but I think this traces back to his profound political inexperience. Musk has experience as a business executive. He’s never been in this situation before and just doesn’t know how to navigate it. In flailing, he makes his situation worse and worse.

First off, the proposal that Vance should replace Trump was just stupid. No reasonably intelligent person would even suggest a move like that. There were no real grounds to impeach Trump and Vance’s political future depends on Trump’s support. If Vance were to betray Trump, not only would he have to contend with the future ire of the most powerful organization in conservative politics, but he would also label himself as a betrayer. This is not a good label to have if you want to forge future partnerships.

All Musk really did by proposing impeaching Trump was announce that he was trying to drive a wedge between the two most prominent and important Republican politicians, something that naturally Republicans would be hostile to because a wedge in your party probably means you’re going to start losing elections.

Musk’s proposal to form a party to represent the “80% in the center” is somehow even more moronic. Americans are more politically polarized than ever before. There is no center. One of the few things that Americans of all political persuasions are united by is dislike for Elon Musk. Liberals will never forgive him for the role he played during the election and early Trump administration. They were saying that he was Trump’s co-president. The Biden administration launched more than a dozen punitive investigations of Musk and his businesses before Musk had even attached himself to Trump. If liberals take power, it’s a certainty that they'll resume their efforts with a vengeance.

Conservatives had been more friendly to Musk (there was remarkably little bad blood left over from Musk’s support for DeSantis) but clearly very little support for him as anything other than an eccentric sidekick to Trump. I don’t think anyone beyond the exiles Massie and Paul, the Indian subcontinent, and various paid internet shills took Musk’s side during the dispute. There was no real-world base of support for what Musk was proposing on the Left or the Right, suggesting that Musk was delusional and must have badly misjudged popular sentiment to even attempt this.

Finally, claiming Trump is a pedophile reflects very badly on Musk. First, it’s not true. Trump is perhaps the most heavily scrutinized figure in political history. If there was damning evidence against Trump in the Epstein files or anywhere else, there is no chance that it would not have been leaked or otherwise publicly used against him over the last 8 years of total war against Trump that has been waged by various domestic and international security services. Second, Musk claiming Trump is a pedophile raises the question of why Musk was an eager public supporter of Trump until he suffered the severe professional and personal embarrassment that led him to be booted from the White House.

Musk’s supposed revelation that Trump was in the Epstein files, which was obviously meant to imply that Trump engaged in sexual abuse of children, is obviously only coming from a desire for “revenge” rather than a genuine concern about punishing wrongdoers. Why would anyone knowingly work with a pedophile or conceal that someone is a pedophile? It’s obvious that Musk does not actually believe that Trump is a pedophile and is merely trying to cause problems for a former associate-turned rival. This is not productive behavior. It’s not how adults should act.

Finally, calling someone a pedophile should permanently close the door to cooperating with them on anything in the future, something that I’m not sure Musk intended to do, or at least that Musk should have known not to do if he planned to remain in the world of Trump-dominated conservative politics, which he clearly does.

Anyone conservative who Musk backs in the future must now explain their association with Musk and will be known as an opponent of the largest and most powerful faction in conservative politics. In trying to attack Trump publicly, he doomed any private effort to undermine Trump, which is a good thing because Trump is one of the few conservative politicians who is not completely worthless, but probably not what Musk intended.

What Musk did was not just dumb, it had no chance of success. That’s the worst part, I think: The coup attempt had no hope of achieving its purported goals, the most it could have done was derail a productive effort and allow liberals to win. This is not how internal disputes can be allowed to proceed in a political movement. There is nothing but vanity, ego, and stupidity behind these moves.

Certainly, heavy drug use explains Musk’s erratic behavior, but at every turn Musk just seems to be divorced from reality and lashing out blindly. He has no idea what he’s doing. He is out of his depth. In short, his political inexperience has generated all sorts of problems for himself and others.

As quickly as Musk’s attempted rebellion failed, it’s important to remember that it was harmful even in failure. Musk was an asset and now he’s a huge and permanent liability. He provided Democrats and various anti-Trump bad actors on the Right with ammunition to deploy against Trump and undermine the very necessary implementation of Trump’s agenda. Musk set a terrible example for others, who might mistakenly believe that all this is “normal” rather than a counterproductive clown show. Panic and despair and bad behavior are contagious in modern conditions, where they have become so common that there are no real social barriers to their spread anymore. We are not working with the historical American middle class and the norms that propelled it (and the country) to such success.

So, what is to be done? It’s embarrassing to have to deal with Musk because it begs the question as to why such an unstable and moronic person, who apparently is a heavy drug user, was allowed into such a high position to begin with. However, I think harsh treatment is very necessary anyway. Bad actors often try to create these hostage situations: They cause trouble because they know getting rid of them would be trouble in its own right. In these situations, people are better off shooting the hostage rather than allowing bad behavior to go unpunished forever. As I’m sure most of you have noticed, someone who behaves in this way usually only gets worse.

I wrote most of this article a month ago but decided to sit on it because it was a little unfocused (it might still be) and too harsh after Musk disappeared with his tail between his legs when the coup failed. However, it seems that Musk has elected to once again reenter the public stage to try to block the Big Beautiful Bill, an item that I don’t know much about and don’t care much about beyond the historic increase in immigration funding that the bill will provide (more than $100 billion for border security and internal enforcement, along with numerous increases in fees and taxes to discourage immigration).

There doesn’t seem to be any alternative way to secure this funding in whole or in part, and in my opinion immigration is Trump’s most important issue, so one way or another at the end of the day the bill has to pass.

Having embarrassed himself in the way he has, Musk is likely going to try to play the spoiler forever. Every anti-Trump figure follows the same pattern: They get ejected from practical politics (to which Trump provides the only access) for bad behavior and realize that their only potential path back to influence is to engineer some kind of catastrophic collapse that will get Trump and his supporters out of the way, without regard to the consequences that that collapse, which would entail total liberal victory, might have. That’s what Massie and Paul are trying to do in their attempt to block the BBB. They complain that Trump has not achieved X, Y, or Z campaign promise while simultaneously trying to take away the tools that might allow him to do so.

People assume this kind of sabotage is a natural reaction to an internal political split. It’s not. One of the biggest mistakes I think Trump made was his treatment of former Senator and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. Sessions was an early Trump supporter and outspoken immigration restrictionist, one of the earliest senior and respected politicians to support Trump during his 2016 primary run. Trump requested Sessions resign over Session’s decision to recuse himself from the Russiagate investigation, which caused Trump all sorts of problems. Even though I think Sessions made a big mistake there, it was motivated by Sessions’ good faith understanding of the situation and the law. Trump continued to treat Sessions harshly after Sessions left the White House, supporting his primary opponent during a 2020 Alabama Senate race.

Despite the harsh treatment he received, Sessions has not staked himself out as some outspoken opponent of Trump. He has not engaged in the kind of self-indulgent counterproductive behavior that typifies people who have fallings out with the Trump camp. He hasn’t cynically changed his views to account for his turn of political fortunes. This is all because Jeff Sessions is actually a patriot who loves his country and wants good things to happen to it, even if he’s not involved, while most conservatives who have elected to be anti-Trump are ultimately just in it for themselves. I hope there’s a reconciliation between Sessions and Trumpworld at some point, because people like Sessions are rare and always have something to offer.

For people like Musk, the only way to get rid of the threat they pose is to get rid of them. I hope that Musk is run out of politics and that the Trump administration pulls every lever they can against him: Piss test him at an inconvenient moment and take away his security clearance. Charge him with assault on a federal official for attacking Bessent and throw him in jail. Sue him for defamation by implication for his tweets about the Epstein list. Support shareholder efforts to get him removed from his companies in light of the huge fluctuations in stock prices that his erratic behavior has caused.

Musk has demonstrated that he’s only going to get worse and not learn anything from his mistakes. He made a lot of real contributions, but he did not buy a license to fuck everything up forever and no one should sell him one. Similar harsh treatment should be extended to anyone who supported Musk or who used Musk’s failed moment as an opportunity to get in cheap shots at the Trump admin. These guys are going to do this forever until they’re stopped. People must learn not to interact with them without hostility.

It’s unlikely that someone as wealthy and prominent as Musk could ever be fully removed from politics. However, he can be brought down a peg or three to permanently reduce his influence. He’s broken the law and should suffer the consequences for it. It’s not like Musk can go back to the Left, they’ll set out to kill him if they ever manage to regain political control. Most importantly, harsh treatment of Musk and his associates would demonstrate that bad behavior on the Right actually has consequences, which it currently doesn’t.

There are basically zero standards on the American Right. It is incredible the kind of characters who are tolerated and excused. Someone can engage in bad behavior for years, even directly advocating for liberals to be given full control, and still be welcomed back into the fold for merely saying the right words. That’s a consequence of how most people treat this stuff, as an idea contest or game rather than a struggle for political power with very real effects on you and everyone you know.

You should not expect people to develop standards on their own in America’s basketcase social conditions, they have to be re-imposed. When Wrangel hanged that railroad official, he was giving the spectators very important political experience: The stakes to what they were doing were very high, the fate of their country was on the line. When you were around Wrangel you had better act correct because there was important work to do.

Very good article. Something flying somewhat below the radar is that Tesla’s financial situation has deteriorated substantially since Trump’s election, European sales have now dropped five months in a row, the Cybertruck has flopped, Hyundai/GM/VW EV offerings are starting to find real success. I think Elon’s shortsightedness here can largely be explained by his financial interests, the subsides cut by BBB really are very important to his personal fortune (which is almost all Tesla stock). He is not willing to make sacrifices for larger ambitions. Trump promised Michigan autoworkers fairness and can’t renege. Elon is childish and as you said should be dealt with harshly.

Musk attempting to renegotiate the terms of his support by trying to fracture off a non existant conservative faction which he believed would be personally loyal to him, not only shows his inexperience, it shows the type of environment he steeps himself in at his companies. He mistakenly believed that the utter devotion that his employees have to him is at all representative of the conservative/maga movement. A ridiculous mistake from the outside, but an easy one for an unchecked narcissist to make.