You should really read this introduction to the Russian Revolution: Remastered

Parts 1 through 5 in a single article, with many new additions

A few months ago, I put together a series of articles outlining the Russian Revolution and its immediate aftermath. This was probably the most substantive writing featured on the Substack. My goal with this was to provide a basic frame narrative of this important period that people could use to gain a better understanding of more specific material that they encountered. This series was well received, though I noticed that readership dropped off towards the last article (very lazy).

I’ve decided to join the articles together. There are three reasons for this. First, my initial release of these articles contained many errors of fact and grammar, graciously pointed out by my beloved readers (they were really mean), that have now been corrected. Second, I still read a lot of material about this period on my own, and I’ve added several new extended footnotes (these are great, please read them) and additional paragraphs to provide more background information and better complete the narrative. There is an extensive amount of new material that has been added since the original articles were released. Finally, Substack’s text-to-speech program has gotten much better since the articles were originally released, and I’m hoping people can now just listen to the articles together like a podcast if they want to.

It’s often tough to talk about historical topics these days because people aren’t really speaking the same language anymore. Media and the education system don’t do a good job equipping the public with the fundamental background knowledge it needs. Oftentimes, smart people without any bad intent just don’t know about important events or have such a narrow understanding of those events that it’s tough to put any new information they learn into context.

The results of this lack of general knowledge are what I like to call “islands.” Little factoids or anecdotes that might have some degree of truth to them, but, lacking background information to serve as connective tissue, can end up painting a very misleading picture. People accumulate different islands based on the media they consume or whatever topics they’re interested in. That’s only natural, different people are going to be interested in different things, but it doesn’t lead to very productive discussions. It often seems like people are just exchanging anecdotes with each other. They might agree, they might disagree, but inevitably not a lot is gained. History turns into a mere checklist to be deployed in a Discord argument.

Historical documents are tricky because, even if the documents are interesting, the authors (understandably) assumed that readers would know about things that, 100+ years later and several continents away, they don’t necessarily know about. Even a bit of background knowledge can add a lot to peoples’ understanding of these documents.

Please note, I’m not trying to write a comprehensive history or include every important aspect of the period. I’m really trying to provide a basic frame narrative that can be used by people who don’t have any background information at all. There are lots of important topics that I don’t have space to talk about or, if I did talk about them, they would end up being more of a distraction than anything else. I hope this essay helps you when you explore those topics.

I’m also going to play around with timeline a little bit just for the sake of readability. For instance, the escape of Kornilov and Alexeiev into Cossack territory actually happened before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed, even though I mention the escape after the treaty. With so much going on near-simultaneously, it’s difficult to adhere to a strict chronology and maintain any kind of narrative coherence. I’ll try to bring things up roughly as they occur, but that gets more and more difficult when you’re trying to explain certain events (which may unfold over the course of several months) in detail. For me, readability is king. I want you to finish the article.

I’m not a professional historian, I work in marketing and dropped out of a film studies program in Canada after one semester, but I do read a lot of this stuff. If you’re looking for a more in-depth examination of the Russian Revolution, I strongly recommend Sean McMeekin’s book The Russian Revolution: A New History. That is, without a doubt, the best summary of these events out there. It’s very well-written and easy to understand. Everyone should read it.

Finally, please upgrade to a paid subscription to support my work. Every single subscription really does help me out a great deal. It’s only $5 a month and you get access to all the podcasts on this Substack.

And now, to the essay:

Part I: The February and October Revolution

Although popular histories often refer to a singular “Russian Revolution” that destroyed the Russian Empire, there were actually two major political shifts that occurred in the cataclysmic year of 1917.

The first of these was the February Revolution. Russia mobilized millions of conscripts to fight in World War I against Germany and its allies (collectively known as the Central Powers). Russia was part of an opposing military alliance known as the Allied Powers or Allies, which consisted of Great Britain, France, the United States, and numerous other minor powers. Although Russia’s military performance during that war was not as dismal as it is often made out to be, the societal pressure caused by mass conscription, wartime shortages (both real and imagined), and well-funded propaganda operations sponsored by the German, British, and Japanese governments (the latter two, even though they were members of the Allied Powers with Russia in WWI, still saw Russia as a major geopolitical rival) culminated in a massive loss of confidence in Russian monarch Czar Nicholas II’s ability to govern.

This loss of confidence climaxed in February of 1917. What followed were enormous and endless riots in major cities that the Russian police and military were unable and eventually unwilling to control. Seemingly abandoned by his allies and even some members of the Royal Family (Grand Duke Kirill, the Czar’s first cousin, actually moved his troops away from guarding Czarina Alexandra so that they could swear loyalty to “the Revolution”), Czar Nicholas abdicated his throne.

Czar Nicholas first planned to hand power to his son Alexis (only 12 years old), as the Imperial rules of succession dictated. However, at the last minute, Czar Nicholas decided to instead pass the throne to his younger brother, the popular Grand Duke Michael. Although Nicholas thought this would calm the situation, this deviation from standard constitutional procedures only dumped fuel on the fire. Grand Duke Michael (who had liberal sympathies) refused to accept power, instead turning it over to the Constituent Assembly, the parliament that had formed after the Revolution.

Henceforth, Russian monarchy and Imperial system was replaced by the Provisional Government, an impromptu parliamentary democracy dominated by the major political factions that drove the Revolution. The Provisional Government was headquartered in the Winter Palace, the former residence of the Royal Family. Czar Nicholas and many of his relatives were imprisoned without charges by the new government and held captive. Although the assumption was that Czar Nicholas would be allowed to go into exile in England, British King George V (a close relative of Czar Nicholas) eventually withdrew his offer of asylum, afraid of political backlash from British liberals (including the relatively new and ascendant Labor Party).

Later attempts to exile the royal family were blocked by the emerging power of the Soviets, public workers’ councils that frequently passed decrees that held competing authority with the Provisional Government’s orders. These decrees were largely enforced by mob violence and the threat of shutdowns to critical infrastructure. The largest and most influential Soviet was in the capital Petrograd (usually called St. Petersburg, which had been renamed at the start of World War I over concerns that the city’s name sounded too German). Grand Duke Michael himself was arrested without charges by the Provisional Government as the political situation deteriorated further. Grand Duke Kirill fled the country, abandoning everyone to their fates.

The Provisional Government left much to be desired. The disorder that had toppled the Czar did not end, it only accelerated. Political infighting and petty factional disputes paralyzed the operations of the already-unwieldly Russian state bureaucracy. Making matters worse, the Russian military (which was then still engaged in fierce combat on the frontlines of WWI) began to collapse. This collapse was both due to the general climate of hysteria that prevailed in Russia at the time and dubious “reforms” introduced by the Provisional Government and the Soviets.

Examples of changes to the Russian military forced by the Provisional Government and the Soviets included banning the death penalty in all cases, forbidding traditional military honorifics and saluting, banning signs of rank and unit insignias (which made preventing desertion, then an epidemic, effectively impossible), the introduction of political commissars who could override officers’ orders, and the creation of numerous soldiers’ committees which held frequent democratic referendums on matters essential to military life.

Morale and discipline in the Russian military were immediately destroyed. Men refused orders and frequently assassinated their officers. Millions of conscripts returned home with their weapons to an uncertain future. Basic governmental functions and the fundamentals of economic life began to break down as a growing state of anarchy and hysteria gripped the population.

Seeking support from abroad, the Provisional Government redoubled Russia’s military commitment to the Allied Powers in World War I, which was still raging as Russia entered a state of political collapse. Lavr Kornilov, the only Russian general to have a major victory in the months that followed the February Revolution, became one of the senior leaders of the Provisional Government’s military forces. Although Kornilov had supported the February Revolution, he was still respected in conservative circles. He was widely regarded as a hard-charging officer and was openly hostile to the “reforms” that had crippled the military.

Working with Alexander Kerensky, an outspoken attorney who had become the Provisional Government’s War Minister through dubious political maneuvering, Kornilov began to roll back some of the more destructive policies forced onto the military. Kerensky and Kornilov worked together to organize the “Kerensky Offensive,” a massive military advance that was intended to restart Russia’s momentum on the (then collapsing) Eastern Front against the Central Powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary, and Turkey). Kerensky made himself the central figure of the narrative surrounding the offensive, often visiting the frontlines to speak to the troops about the need to protect Russia’s “Revolutionary Democracy.”

When the Kerensky Offensive finally began in June 1917, it was a near-immediate disaster. Russian troops were simply too demoralized and refused to fight in large numbers after they had left their trenches. As the Germans and Austrians counter-attacked, the Kerensky Offensive quickly turned into a rout for Russia. The Central Powers advanced almost without opposition deeper into Russian-controlled territory and the Provisional Government was discredited.

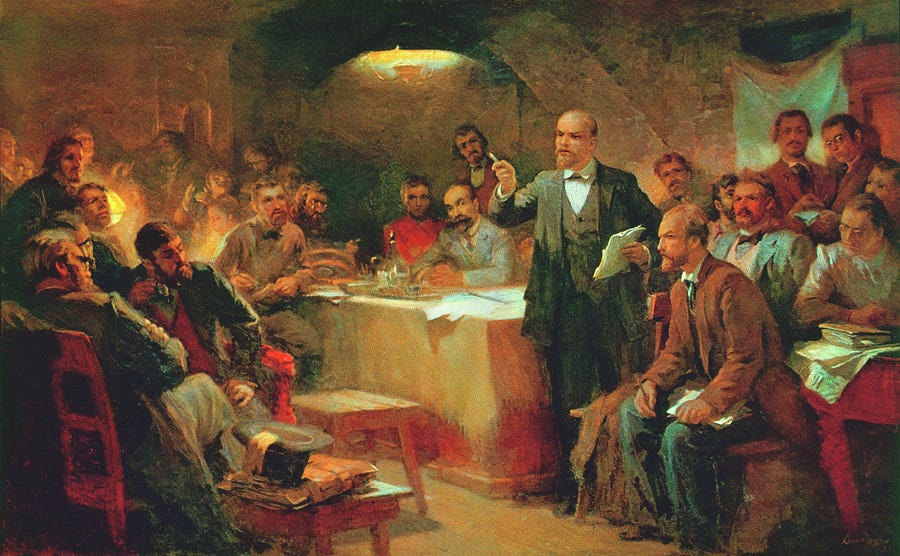

The Bolsheviks, a small communist political party that had risen to prominence after being gifted large amounts of cash by German intelligence as part of an effort to remove Russia from the war, plotted to overthrow the Provisional Government. The Bolsheviks controlled, or at least heavily manipulated, many of the Soviets in major cities, and frequently staged violent demonstrations and attacks on rivals. Although the Bolsheviks did not have buy-in from a large swath of Russian society, they did have the support of many rebellious soldiers and sailors, particularly those in Petrograd. One of the key distinctions between the Bolsheviks and other political parties was the Bolshevik promise to withdraw from the war immediately.

The Provisional Government’s ruling coalition collapsed in early July over both the humiliations of the Kerensky Offensive and continued disputes over the autonomy of the provinces that made up the Ukraine (When authors add “the” before Ukraine is used to refer to the region, divorced from a national context), which was then considered a part of Russia. The Prime Minister and other cabinet officials announced their resignations.

During the July Days, the Bolsheviks’ supporters (possibly without the approval of the central party) held massive armed marches throughout Petrograd. They attacked passersby, stormed private homes, and seized vehicles and strategic points. The violence exceeded that of the February Revolution in many areas. They also attempted to force the Soviets (which, although they were heavily influenced the Bolsheviks, also had significant numbers of members of other leftwing parties) to formally launch a coup against the Provisional Government. The Soviets waffled and eventually Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin himself disavowed the attempted takeover.

This disavowal came too late, however. Public opinion shifted decisively against the Bolsheviks, who were machinegunned in the streets by loyalist troops without much backlash. Many prominent Bolsheviks, including Petrograd Soviet chairman Leon Trotsky, were arrested and Lenin had to flee the country.

Kerensky used the opportunity to rise to the top of the Provisional Government, becoming Prime Minister. He made Kornilov Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the military, banned public demonstrations, and took other steps to restore stability to Russia. This stability was short-lived, however, as Kerensky’s political ambitions far exceeded his abilities. Styling himself as a Napoleon-esque figure committed to saving liberal democracy by any means necessary, Kerensky made blunder after blunder and united nearly all factions on the Left and the Right against him.

These blunders eventually came to a head in September 1917 during an incident that would become known as the Kornilov Affair. Kerensky had requested that Kornilov prepare a special detachment of troops to “restore order” in Petrograd. This likely entailed liquidating the Petrograd Soviet by force after its many months of disruptions and open revolutionary activity. Russian life had turned into a never-ending hostage situation, directed by the whims of the Soviets. The troops assembled to crush the Petrograd Soviet were to be led by General Krymov.

However, a former government minister named V. N. Lvov presented himself Kornilov, falsely claiming to be an emissary of Kerensky. Although Lvov was well-connected in conservative circles, he was regarded as an unstable character. He had been snubbed by Kerensky months before, failing to receive an expected cabinet appointment. Lvov learned that Kornilov wished for even more aggressive state crackdown on revolutionary disorder and, without any authority from the Provisional Government, asked Kornilov what would entice Kornilov to begin a temporary military dictatorship with the permission of the Provisional Government.

Lvov then travelled to Kerensky and falsely claimed to be an emissary of Kornilov. He presented Kornilov’s hypothetical conditions for accepting a temporary military dictatorship from the Provisional Government as though they were a list of Kornilov’s demands to Kerensky. The meeting did not go well. Lvov threatened Kerensky’s life and falsely claimed that a military coup led by Kornilov was imminent.

Kerensky, rather than reaching out to Kornilov directly about these claims, began to impersonate Lvov in a series of vague communications to Kornilov and other military leaders. After receiving confused answers in response, Kerensky publicly declared that Kornilov was attempting a coup and ordered his arrest.

In response, Kornilov ordered Krymov’s troops to advance on the capital and proceed with the planned liquidation of the Petrograd Soviet. It’s unclear why he gave this order. It’s possible that Kornilov was actually attempting to overthrow the Provisional Government after learning of Kerensky’s proclamation. It’s also possible that he believed that this seemingly unprovoked move to arrest him was actually a sign that a leftwing coup led by either the Soviets or the Bolsheviks was already in progress.

Whatever the reason for Kornilov’s order, Krymov’s force lost momentum as it approached the capital. Many troops refused to proceed with what they believed was a military coup and there was frequent sabotage of telegraph and rail lines, contributing to the confusion.

In a last-ditch effort to “defend” Petrograd, Kerensky ordered that all the Bolsheviks who had been arrested following the July Days be released from prison and freely handed out heavy weapons to anyone who would take them in Petrograd. These weapons were not returned after the crisis ended.

Krymov and a small escort travelled ahead of the main force to meet with Kerensky and negotiate or at least obtain some clarity as to what was actually happening. After the meeting with Kerensky, Krymov shot himself for unclear reasons.

Kornilov voluntarily surrendered and was replaced as the head of the Russian military by General Mikhail Alexeiev (who personally arrested Kornilov, leading to lifelong bad blood between the two men). Complicating matters was the fact that many conservative officials and military leaders mistakenly believed that Kornilov had actually been planning a coup, and came out in support of a Kornilov-led military dictatorship to end the disastrous reign of the Provisional Government. Kornilov and other military leaders who supported the alleged rebellion, such as General Anton Denikin, were imprisoned by troops who sympathized with them at Bykhov Fortress.

Although Kerensky had managed to save the Provisional Government, which might have never been under real threat, the months of chaos had thoroughly discredited him and it. The Bolsheviks, released from prison and without the fear of interference from conservative military officers (who, if they weren’t jailed, were thoroughly disorganized), redoubled their efforts to topple the Provisional Government. Lenin returned from exile and he and Trotsky began laying the groundwork for a coup to be held the following month in October.

Plans for the Bolshevik coup leaked publicly. However, rather than take action against the Bolsheviks, Kerensky instead adopted a policy of “No enemies to the left” and began further (increasingly dubious) suppression of conservative officers and political associations in an attempt to ingratiate himself with leftist parties and remove any motivation for a coup. Several newspapers were ordered shuttered. Kerensky also announced the formal dissolution of the monarchy and the Provisional Government, replacing it with the (very short-lived) Russian Republic.

As Bolshevik men and arms flowed freely into Petrograd, numerous factions and organizations attempted to halt the obviously imminent overthrow of the government. Loyal soldiers stormed and destroyed a pro-Bolshevik newspaper printing facility. One night, a group of officers, apparently organized by high-level members of the government, surrounded the Smolny Institute, which the Bolsheviks had taken as their headquarters, and planned to kill everyone inside. However, they were never given the “Go” order and the group soon disbanded.

On October 25, 1917, the Bolsheviks launched their coup in Petrograd. This was known as the October Revolution. There was relatively little fighting. Few people were willing to defend the Kerensky government, particularly against the overwhelming odds that had been assembled by the Bolsheviks in the city. Nearly all of the local military garrison supported the coup. A Bolshevik naval flotilla entered the Neva River (which runs through Petrograd) and began to bombard the Winter Palace, which was soon stormed and captured. Virtually every member of Kerensky’s government was taken prisoner or killed except for Kerensky, who fled the capitol building in disguise without warning anyone of his departure.

Escaping the Winter Palace by car, Kerensky travelled outside the city until he found a loyal garrison under command of Pyotr Krasnov, who was then a relatively obscure figure but would soon come to play a major role later in the drama. Although this force gained ground initially, they soon encountered fierce opposition and, realizing how outnumbered they were, scattered. Kerensky, with no remaining allies in Russia and no troops, fled the country.

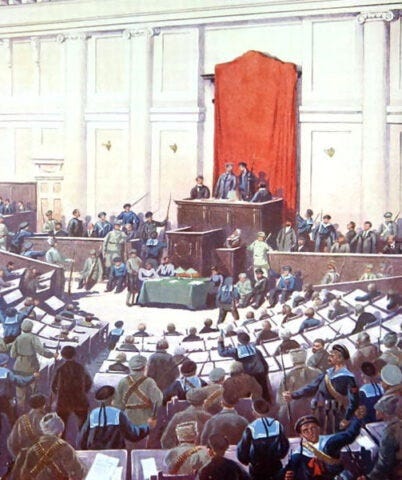

The coup was almost entirely successful, though some fighting between the Bolsheviks and forces loyal to the old government continued in a few areas that lacked a significant Bolshevik presence. The Bolsheviks and the Soviets announced the creation of a new government for Russia, a Soviet Republic. This new Bolshevik-dominated government had no legal authority and was not recognized by any other political party in Russia. The grim shadow of civil war soon fell over the country.

II. Post-Revolution Russian Politics/The Aftermath of the October Revolution

Petrograd fell under control of the Bolsheviks, who proclaimed the fall of the Provisional Government and the creation of a new Soviet Republic in Russia. Fighting between the Bolsheviks and loyalist troops continued for several weeks in Moscow, though in most parts of the country there was no fighting at all. Everyone was just waiting to see what would happen next. Bolshevik delegations arrived in many cities and claimed control, although they had no legal authority and the political situation was murky at best. Many areas refused to recognize these delegations and even drove them out with force. The Bolshevik base of support did not extend far outside major cities and a few radicalized military bases.

Now is a good time to describe Russian politics after the February Revolution that toppled Russia’s monarch, Czar Nicholas II. The February Revolution brought together Russian leftists and some Russian rightwingers to create the Provisional Government. However, the Provisional Government was just intended to act as a caretaker until elections could be held for the Constituent Assembly, a parliament that would rewrite Russia’s constitution and create a permanent democratic republic.

Absolute monarchists (a significant minority of Russia’s population at the time of the February Revolution) who favored a return to the old Czarist system were excluded from the Provisional Government. The major Russian parties vying for positions in the Provisional Government and proposed-Constituent Assembly were:

The Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) - Democratic socialists who had existed as a political party for several decades (mostly outside of government). Their base of support was the rural peasantry and their main goal was redistributing public and private land to the peasants. The SRs had been discredited in the eyes of more conservative-minded Russians because of the party’s brutal and widespread terrorist campaign following the unsuccessful 1905 Revolution. Despite their radical agenda, the SRs opposed further revolutionary changes to the Provisional Government and (though there was some internal disagreement) opposed Russia’s exit from WWI. This was the largest and most popular party after the February Revolution, with support generally around 40% of the population.

The Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) - Liberal “reform” party that supported a number of progressive policies from the eventual implementation of a constitutional monarchy to universal suffrage and the protection of civil liberties. The party was created by radical nobles but moderated over time to appeal to the educated classes more generally. It favored stability. As this was the only non-socialist political party allowed in government after the February Revolution, many conservatives who would otherwise have been unrepresented joined its ranks. The Kadets were ardent Russian nationalists and opposed Russia’s exit from WWI. This was the second most popular party and the party that exercised the most control over the Provisional Government. Support for the Kadets typically hovered near 30% of the population, including broader rightwing coalition that eventually formed around it.

The Bolsheviks - A radical communist party that advocated for the abolition of national and class barriers, along with an end to private property. Its leadership openly supported armed violence in order to fuel revolutionary change. Their base of support came from urban workers and soldiers. Although the party was relatively unpopular before WWI, the Bolsheviks received massive (secret) funding from Germany, allowing them to substantially expand their payrolls and propaganda operations. Naturally, the Bolsheviks favored Russia’s withdrawal from WWI (enhancing their popularity among many people who didn’t buy into their economic agenda). They exercised disproportionate control over the Soviets, public workers councils that issued decrees with authority that competed with that of the Provisional Government. Support for the Bolsheviks typically ranged between 10% and 20% of the population, depending on whatever the prevailing political winds were.

The Mensheviks - A party that split from the Bolsheviks when both were created in 1903. They had largely the same platform as the Bolsheviks, though the Mensheviks favored peaceful activism rather than revolutionary violence to achieve their goals. Their support was always smaller than that of the Bolsheviks, and a large minority of their members defected to the Bolsheviks after the February Revolution over the Menshevik support for the continuation of WWI. Despite their diminished national significance following the defection, they maintained significant local majorities in Transcaucasia and Georgia.

The Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SRs) - A faction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party that eventually became its own separate entity after the October Revolution. This party sprang out of the SRs’s (much more radical) local organization in Petrograd. It had mostly the same agenda as the main party, though it differed from them in advocating for the overthrow of the Provisional Government and transfer of all power to the Soviets. The Left SRs typically aligned with the Bolsheviks, though they opposed any exit from WWI, albeit for internationalist reasons rather than the typical nationalist ones (the Left SRs didn’t want to make peace with Germany, an imperialist power).

The Bolshevik coup in Petrograd in October 1917 was condemned by every other major party as an illegal seizure of power.

Although Bolshevik-aligned forces nominally controlled Petrograd, a state of absolute confusion prevailed. There had been little actual fighting, most participants in the revolution were not part of any larger conspiracy but rather merely going along with the mob. The stunning Bolshevik success had mainly resulted from very few people being willing to risk their lives to defend Kerensky’s disastrous government.

The first serious opposition to the Bolsheviks emerged from the Junkers. Junkers were military school cadets, typically teenagers, training to become officers. Junker schools existed in many major cities across Russia and were almost always hotbeds of conservative sentiment. The Junkers hadn’t been deployed to the frontlines yet and were spared the demoralizing conditions that members of the Russian military had suffered under for years. Furthermore, as visible representatives of Russia’s military traditions, they were frequently targets of abuse from urban workers, deserting soldiers, and liberal activists, hardening the Junkers’ anti-revolutionary stance.

Although the Junkers were mostly teenagers, they had weapons, training, uniforms, and military organization. This made them a fearsome force in a city dominated by largely disorganized mobs. Several days after the Bolshevik coup, on October 27th, they launched the Junker Mutiny with support from Committee for the Salvation of the Homeland and the Revolution, a short-lived alliance between the Kadets, SRs, Mensheviks, and various other local political entities.

Cadets from several different Junker schools advanced on strategic points around Petrograd simultaneously. They seized the all-important Petrograd telephone exchange, cutting off communications to and from the city. They also captured Bolshevik strongholds like the Hotel Astoria and even disabled the power at the Smolny Institute, the headquarters for the entire Bolshevik Party.

Despite the Junkers’ remarkable success, anti-Bolshevik political groups were unwilling to provide them with anything other than moral support. No mass rising accompanied these gains and the teenagers soon learned that most of the adults who had urged them forward were not willing to actually stick their necks out to do anything about the Bolsheviks.

The Bolsheviks counterattacked with a large number of Red Guards, ideologically-motivated paramilitary units, and drove the Junkers into the Vladimir Military School. After suffering heavy casualties in an attempt to storm the building, the Bolsheviks wheeled artillery pieces into the city and bombarded the school into rubble. Hundreds were killed on both sides, though the Bolsheviks retained control of Petrograd and a growing number of urban areas.

One revealing consequence of the Junker Mutiny was the fall of the Constitutional Democratic Party, also known as the Kadets. Although the Constitutional Democratic Party’s leadership could be tied to the Junker Mutiny through its support of the Committee for the Salvation of the Homeland and the Revolution (which in practice provided virtually no help to the Junkers), the biggest problem for the party came from its name.

The “Kadet” nickname originated from the abbreviation of the party’s name in Russian: Konstitutsionno-Demokraticheskaya partiya. “K-D” sounds like “cadet” in Russian. The Kadets weren’t military cadets or anything like that, it was just a play on words. However, most Russians of the time were illiterate. Only 37% of men and 17% of women over the age of 7 could read. When news went out that military cadets had risen up to protect the hated Kerensky government, many people (not unreasonably) believed that it was actually the Kadet Party leading the counterrevolution.

This confusion was ruthlessly exploited by the Bolsheviks, who tried at every turn to associate the liberal Kadets with the far more conservative (and unpopular) military cadets. Support for the Kadet Party dropped substantially as many supporters and local officials began to fear reprisal for the Kadets’ supposed role in the failed uprising.

One defining feature of the Bolsheviks was a total disregard for the truth in all interactions with everyone else. The Bolshevik’s platform for Russia could be (and was) anything that would make the Bolsheviks popular at the moment and harm the Bolsheviks’ rivals. There was no regard for consistency. They would lie about everything, all the time. For instance, although the Bolsheviks called for the abolition of private land ownership entirely, they publicly adopted the Socialist Revolutionaries’ more popular land policy (which would distribute land to peasants in communal (but [but not state-owned] plots). They had no intention of implementing this policy, they just knew it was popular and that publicly adopting it would undercut the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Having successfully ended the military threat to their new regime from both Kerensky and the Junkers, the Bolsheviks set about consolidating their power politically. Although the SRs and Mensheviks had competed with the Bolsheviks for control of the Soviets before the October Revolution, after the revolution they were almost entirely excluded from them (both parties had walked out in protest at a critical vote in the influential Petrograd Soviet upon learning of the planned Bolshevik uprising).

At that point, nearly everyone regarded the Bolshevik coup as illegitimate even if they weren’t willing to risk civil war to oppose it. However, the people most likely to actually resist the Bolsheviks takeover, conservative military officers, were still spread across thousands of miles of Russia’s frontline in World War I. Although the situation before the October Revolution had been bad for Russia’s military, after the revolution it entered into a state of freefall collapse.

Assassinations of officers became an epidemic. In Kronstadt, headquarters of the Russian Baltic Fleet, the Bolsheviks received overwhelming support. Thousands of officers were executed by their men merely for being officers. Similar atrocities occurred all over the front. Baltic sailors (also called Kronstadt sailors) became infamous throughout the revolution and its aftermath for their brutality. These men formed the military backbone of the early Bolshevik regime and were used to terrorize the civilian population.

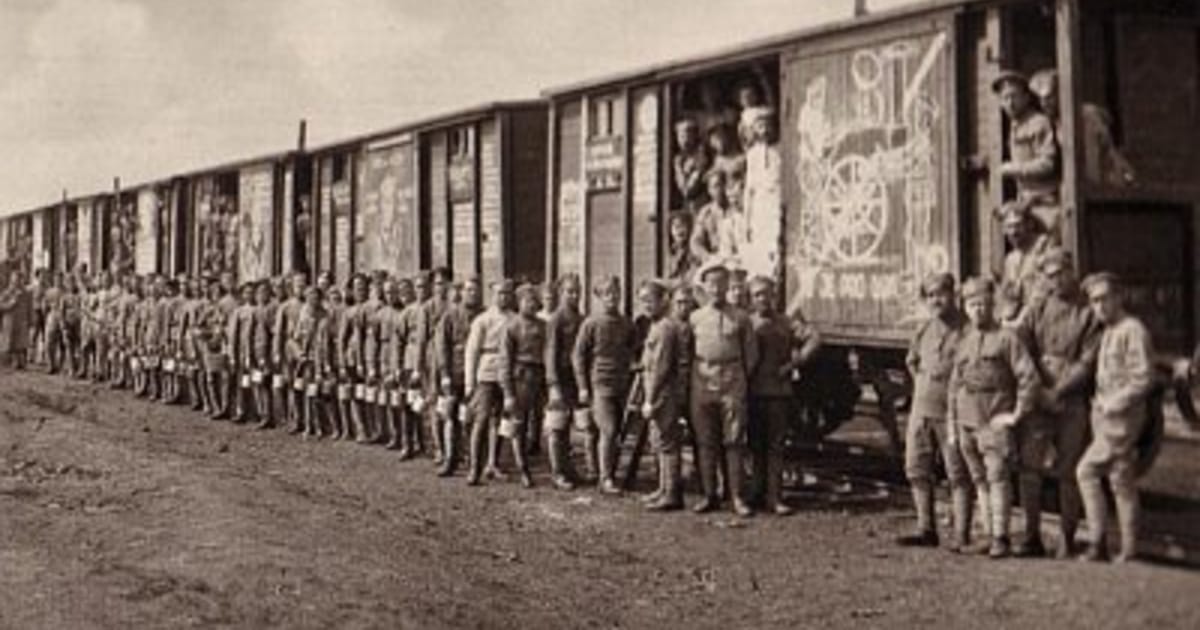

Another pillar of early Bolshevik military power was the Latvian Riflemen. Latvia1 was controlled by the Russian Empire at the start of World War I. The Russian military often raised national units for convenience’s sake. However, the dramatic failures of Russia on the Eastern Front after the February Revolution had led to Latvia’s conquest by Germany. The Latvian Riflemen had a string of bad Russian senior officers, which contributed to the radicalization and alienation of the men. As Russia began a process of political collapse, the Latvians (despite having little affinity for Bolshevism as an ideology) threw their lot with the Bolsheviks. As one of the few intact and well-disciplined military units still operating in what was turning into an apocalyptic situation in the interior of Russia, the Latvian Riflemen became the elite enforcers of the Bolsheviks’ will.

Tens of thousands of government bureaucrats and other employees in critical sectors like banking and transportation (including railroad union members) refused to cooperate with the Bolsheviks as they attempted to wield the machinery of the Russian state. They went on strike and obstructed access important documents and material. Significantly, employees of the state bank refused to allow the Bolsheviks to access Russia’s state funds, creating a financial crisis for the Bolsheviks.

In the backdrop of this fairly widespread resistance, the Bolsheviks agreed to hold elections for the long-awaited Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1917, when they had originally been scheduled by the Provisional Government.

The November elections produced results that were less than desirable for Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin. Although the Bolsheviks made a respectable showing, gathering nearly 24% of the vote, greater public support than they had ever obtained before, they came in a decisive second to the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which gathered 40% of the vote (and nearly 50% if you include the Socialist Revolutionary Party’s Ukrainian offshoot). The Bolsheviks simply had limited popularity outside of their urban strongholds and radicalized military units.

The Constituent Assembly, Russia’s first truly democratically elected parliament and the product of centuries of struggle by Russian radicals, was allowed to meet for approximately 13 hours on January 18, 1918 before the Bolsheviks ordered it dissolved. All power was henceforth transferred to the Soviets, which were carefully controlled by Bolshevik Central Committee. The Bolsheviks formed a dubious coalition government with the Left SRs (who had received about 1% of the vote) and several rogue Mensheviks (around 3% of the vote) and began firing into the crowds that had assembled to support the Constituent Assembly.

It became clear to virtually everyone that the Bolsheviks had created a one-party dictatorship for themselves. Strikebreaking became the new priority for the Bolshevik government. In order to deal with internal threats, Lenin ordered the creation of the Cheka, a new Bolshevik secret police organization. Rogue government workers were threatened and even had their families held hostage by the Cheka in order to guarantee their compliance. Although the death penalty had formally been banned by the Bolsheviks, executions became commonplace.

A massive robbery campaign began as the Bolsheviks nationalized the holdings (including personal deposits from private citizens) of all major banks. These stolen goods were to be smuggled out of the country and sold overseas at greatly reduced prices in order to fund Bolshevik activities abroad (no foreign powers would allow the Bolsheviks to access Russia’s foreign reserves). Common criminals were released from prison en masse and often recruited by the Bolsheviks to the Red Guards. Law and order totally broke down in Bolshevik-controlled areas.

As Russia entered its darkest political period yet, the German Army was once again advancing nearly unopposed across Russian-controlled territory. Lenin was desperate to end the war quickly in order to allow the Bolsheviks to concentrate on their internal enemies. On March 3, 1918, Lenin agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, led by Germany.

The terms of the treaty were humiliating. The Bolsheviks agreed to surrender Russian control of Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and several provinces in the Caucuses. The territory lost accounted for roughly 34% of the former Russian empire's population, 54% of its industrial land, 89% of its coalfields, and 26% of its railways. The Bolsheviks also agreed to pay significant “war reparations” to Germany, mostly in the form of state gold reserves that the Bolsheviks had managed to gain access to (most had been moved outside Petrograd before the Revolution as the situation deteriorated) and private property looted during their nationalization of the banks. The Left SRs formally broke with the Bolsheviks in protest over the agreement, claiming that the Bolsheviks were little better than German agents (which, although this was not publicly known at the time, they were).

However humiliating these concessions may have been, Lenin was happy to be out of the war as enemies within Russia closed in on him from all sides. Also entering into the Bolsheviks’ calculus was that, even as Germany was triumphant on the Eastern Front, on the Western Front its situation had become untenable with the entry of America into the war on the side of the Allies. It seemed unlikely that any agreement the Bolsheviks made with the current German government would last for very long. Furthermore, with the Russian military in a state of collapse, at that point the Bolsheviks could not have exercised control over the areas they gave away even if they had wanted to.

As the Bolsheviks stood on unsteady ground at the start of 1918, in the south of Russia the most serious organized opposition to the Bolshevik was coming into being. General Lavr Kornilov, the widely respected former head of the Russian military, had escaped2 from Bykhov Fortress, where he had been confined since the Kornilov Affair, along with other major Russian military figures like General Anton Denikin. These officers headed into Cossack territory near the Don and Kuban rivers, where local authorities had refused to surrender power to the Bolsheviks.

Further contributing to the efforts of the early counterrevolutionaries was General Mikhail Alexeiev, another former head of the Russian military, who had gone into hiding after the October Revolution and built a secret network known as the Alexeiv Organization to smuggle military cadets (who were being hunted by the Bolsheviks after the Junker Mutiny), volunteers, weapons, and critical war material towards South Russia with the hope that a proper army could be formed to fight the Reds, a name the Bolsheviks had taken for themselves.

To contrast themselves with the Reds, the burgeoning anti-Bolshevik coalition was collectively dubbed the White Movement. Although politically schizophrenic, bringing monarchists, republicans, liberals, and moderate socialists under a single banner, the Whites were united in their opposition to the Bolshevik dictatorship and desire for the renewal of Russia after years of disaster.

After 4 months of chaos following the October Revolution, Russia was on the edge of a full-blown civil war. Soldiers who had spent years on the frontlines of World War I prepared for an even greater struggle that would determine the fate of their nation.

III. National and Ethnic Divisions within the Russian Empire/The Ice March

Months after the October Revolution, although Bolshevik political control had solidified over the major cities of European Russia (the western and most populous part of the country, contrasted with the sparsely populated eastern regions that include Siberia), the grasp of the Red Army, the Bolshevik military organization created in January 1918, on many areas both in and outside of Russia was slipping.

The Russian Empire, formally proclaimed in 1719 AD, had once controlled many non-Russian nations (or aspirational nations). This imperial control of foreign lands under Czar Nicholas II of the Romanov dynasty was made somewhat dubious after the February Revolution, which saw Czar Nicholas deposed and replaced by the Provisional Government. Although the emperor was gone and the new regime was dominated by socialists and liberals, the Provisional Government retained a Russian maximalist character and refused to grant independence to Russia’s subject nations even as the Russian Empire fell apart.

Despite the Provisional Government’s best efforts, the chaos of the February Revolution and subsequent “reforms” to the military introduced by radical leftists caused the complete collapse of the Russian Army on the frontlines of World War I. Although Russia had made some impressive gains earlier in the war (one common misconception concerning the Russian Revolution is that Russia’s military record in WWI was uniformly terrible), as the Russian Army began to disintegrate the German and Austrian militaries advanced almost without opposition deeper into Russian-controlled territory.

The unchecked advance of the enemy into Russian territory had many consequences. One was the rise of long-simmering nationalist movements in previously Russian-controlled nations like Poland, Finland, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Ukraine. With the Russians in retreat, nationalists of all stripes saw their opportunity to finally achieve independence.

The most notable (and successful) of these early independence efforts came from Finland and Ukraine. Finland had a unique political status compared to most nations in the Russian Empire: It had been a Grand Duchy for nearly 100 years, ever since Russia had won control of the territory in a conflict with Sweden in 1809. As a Grand Duchy, Finland was still subject to Russia’s financial and foreign policy whims. However, the nation retained a relatively high degree of autonomy within the Russian Empire. Finns were exempted from conscription in the Russian Army and even maintained their own parliament at various periods.

It was this long-standing political tradition that allowed the Finns to capitalize on the collapse of Russia’s government. After the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks had proclaimed the general right to self-determination, including the right of complete secession, for the “Peoples of Russia.” Finland quickly reformed its legislature and issued a Declaration of Independence on November 15, 1917. The Bolsheviks, not wanting to provoke further conflicts at that moment, officially recognized Finland as an independent nation a few weeks later.

As later events would reveal, Bolshevik respect for the independence of formerly Russian-controlled nations was non-existent. The Bolsheviks quickly set up a local puppet party in newly independent Finland, backed with force by pro-Bolshevik Russian soldiers still stationed in the region (who simply refused to leave). Less than a month after it had obtained independence, Finland was heading towards a Bolshevik revolution of its own.

Ukraine is a nation that is distinct from but has a close and complex relationship with Russia, owing to its shared roots with the modern Russian state. The Kievan Rus', based in the modern Ukrainian capital of Kiev, was the first East Slavic nation (both ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Russians are part of the Slavic ethno-linguistic group), beginning in the 9th century. Gradually, the medieval power base of this nation and its successors shifted away from Kiev and towards Moscow.

Eventually, regional influence tilted heavily towards Russia and Ukraine fell under Russian control. Although the Ukrainian language and ethnicity always predominated in rural areas, in many urban centers (which often had their origins as Russian frontier forts) Russian was spoken almost exclusively and the population consisted of significant minorities or outright majorities of ethnic Russians. Some Ukrainian cities, like the strategically important port of Odessa, had been built by Russian monarchs from scratch in sparsely populated areas as colonial projects.

Ukrainian nationalism had been a major intellectual force for decades before the revolutions of 1917, often associated with leftwing or populist opposition to the Imperial government. After the February Revolution, Ukrainian nationalists saw their opportunity and formed the Central Rada of Ukraine, a parliament to represent all the Russian provinces generally considered to make up Ukraine. Although the Central Rada didn’t seek independence at that point (few wanted to risk civil war), its regional authority was grudgingly recognized by the Russian Provisional Government.

When the October Revolution occurred in Petrograd, the Central Rada refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Bolshevik takeover and declared Ukraine’s independence from Russia, eventually creating the Ukrainian People's Republic.

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was dominated by the local branch of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (the political party that had won the largest number votes in the Constituent Assembly before it was dissolved by the Bolsheviks). However, the UPR did not have a professional military. This made defending Ukraine from the uprisings of local Bolsheviks after the October Revolution very difficult. In November 1917, it was only a last-ditch alliance between Ukrainian nationalist forces and pro-Russian monarchist and conservative officers (who had begun gathering in the few major cities not under Bolshevik control as the Russian Army disintegrated) that saved Kiev from a Bolshevik takeover.

In a move that would become commonplace during the Russian Civil War, after the victory in Kiev the nationalists ultimately sought a compromise with the Bolsheviks (who were viewed as a temporary and relatively minor threat) rather than with the pro-Russian officers who had always been hostile to their independence. The defeated Bolsheviks were released from prison, after which they immediately set up a Ukrainian Bolshevik puppet government in Kharkov. The pro-Russian military officers who had just helped to defeat the Bolsheviks were surprise attacked by a combined Ukrainian nationalist and Bolshevik force and driven out of Kiev.

Still without a professional army of its own and lacking the expertise of the former Russian military officers, the UPR was poorly prepared when the Bolsheviks regrouped and launched an even larger uprising months later. Kiev fell under control of the Bolsheviks in February 1918 and the UPR government fled to the countryside.

Another major consequence of the Russian Army’s collapse on the Eastern Front of World War I was the opening of the Pale of Settlement. The Pale of Settlement was a range of territory in the Russian Empire, mostly in Poland, Belarus, Lithuania and modern-day Ukraine, where Jewish people could obtain permanent residence. Outside of this area, it was very difficult for Jews to work, travel, or live permanently.

Conditions of all kinds in the Pale of Settlement were bleak and tensions between Jews and the surrounding ethnic and religious majority populations of these areas (most inhabitants of the region were both Slavic and Eastern Orthodox Christians) always ran high. There had been centuries of offence and retaliation from Jews and non-Jews alike. Frequent anti-Jewish pogroms (a term for riots usually associated with attacks on Jews) as well as provocations from some Jewish “self-defense” militias and Jewish-dominated terrorist organizations created a seemingly never-ending cycle of violence. Owing in part to these centuries of bad blood and the numerous legal discriminations placed on them (such as restrictions on employment and admission to schools) by the Russian government, Jews were often drawn to radical leftwing movements both inside Russian territory and abroad.

As the frontlines of World War I drew close to the Pale of Settlement, the Russian government temporarily lifted restrictions on Jews’ freedom of movement to allow them to evacuate from the warzone. The lifting of these restrictions later became permanent after the February Revolution when the Provisional Government ended all legal discrimination along ethnic and religious lines in 1917.

The lifting of restrictions on Jews’ freedom of movement in 1915 was not received very warmly by Jews because it was accompanied by mandatory deportation orders. Thousands of Jews (as well as ethnic Germans and Circassians [a primarily Muslim ethnic group that had originated in the Caucuses but had been scattered throughout the Russian Empire after several periods of ethnic cleansing]) were ordered deported from their homes close to the frontlines. Then-Chief of Staff of the Russian Army Nikolai Yanushkevich3 claimed that Jewish civilians near the combat zone would be too pro-German, either acting as spies or saboteurs. No provisions were made for the safety, health, or property of the deportees, and the deportations were done without any concern for the deportees’ age or condition. Although the deportation order was rescinded in many places as unnecessary or unworkable, it was often replaced with a hostage-taking system that further alarmed and alienated the Jews of the region.

The opening of the Pale of Settlement sent tens of thousands of dissatisfied Jews (among many other refugees) into Russia’s major cities at a time when Russia was undergoing its most massive political, social, and economic upheaval in centuries. Unemployed, penniless, and without stabilizing local connections, many of these refugees became prime recruits for radical groups like the Bolsheviks.

High-profile Bolshevik leaders like Party Chairman Vladimir Lenin and Foreign Minister (and later head of the Red Army) Leon Trotsky, who had defected to the Bolsheviks from the Mensheviks after the February Revolution, were Jewish (Lenin being only a quarter-so). This contributed to the popular image of Bolshevism as an almost exclusively Jewish phenomenon, which it was not. However, although the Jewish role in the Russian Revolution is often overstated or oversimplified, Jews were certainly greatly overrepresented in terms of their numbers and influence in all revolutionary organizations, including and especially the Bolsheviks.

It’s important to note that Lenin, Trotsky, and many other Jewish professional revolutionaries spent only a small part of their lives in Russia or Russian-controlled territory. As members of diaspora radical communities in Western Europe and America, these men were culturally and socially distant from the Jews in isolated villages who were most often subjected to “retaliatory” violence during and after the Revolution.

As nationalist movements grew stronger, particularly in Ukraine, ethnic violence became commonplace against both Jews and Germans.

Germans had played an important role in Russian history for centuries. The Baltic Germans, ethnic Germans who settled in modern day Latvia and Lithuania, had an outsized presence in Russia’s military and nobility. General Pyotr Wrangel, who would play a major role later in the Russian Civil War, came from a prestigious Baltic German aristocratic family.

Owing to their prominent role in Russian high society, the Baltic Germans were considered a loyalist ethnic group and often targeted by the Bolsheviks (as well as nationalist movements in the newly-independent Baltic states) both during and after the Russian Civil War.

The Dutch Mennonites, ethnic Germans invited to settle the Ukraine’s richest agricultural region by Russian monarch Catherine the Great in the 1700s, were also the target of great repression during and after the Revolution. Dutch Mennonites were ethnically and religiously distinct from the surrounding majority population and found themselves in a precarious position as Russian society imploded.

Anti-German sentiment ran high in Russian territory owing to World War I. The pre-Revolution Imperial Russian government had tentative plans to deport German settlers in Ukraine to Siberia based on (unsubstantiated) fears that they would engage in sabotage on behalf of the advancing German Army. Czarina Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Czar Nicholas, was often the subject of cruel (and mostly untrue) attacks from critics of the Czar, who suggested that her German heritage led her to sabotage Russia’s WWI efforts.

The defeated UPR still dominated most areas of Ukraine outside the Bolshevik-controlled major cities. Troops under the nominal control (in reality this force was largely disorganized and lacked a clear chain-of-command) of UPR military chief Symon Petliura launched a reign of terror in the countryside. Petliura’s men would massacre tens of thousands of non-ethnic Ukrainian civilians, particularly Jews, Poles, Hungarians, and Greeks,4 over the course of the Russian Civil War.

Further contributing to the declining humanitarian situation in rural Ukraine was the rise of anarchism as a social fad. The informal anarchist Black Army of Nestor Makhno, a Ukrainian peasant turned guerrilla leader, embarked on a massive robbery campaign targeting the middle and upper classes. These robberies gradually became a full-on ethnic cleansing campaign targeting non-ethnic Ukrainians.

Particularly cruel treatment from the anarchists was directed at German Mennonites. The Mennonites were pacifists, but, owing to their relative prosperity, were frequently the targets of anger from surrounding Ukrainian peasant populations. This resentment of the better-off grew to epidemic proportions as the political turmoil that had overtaken the Russian Empire became a total economic collapse accompanied by mass unemployment, shortages of all goods, and famine.

Mass rapes and executions committed by anarchist bands became commonplace. Many German Mennonite communities were literally wiped off the map. The German Mennonite population in the Ukraine would be largely exterminated by the end of the decade owing to both anarchist massacres during the Russian Civil War and later official repression (indistinguishable from an ethnic cleansing campaign) of Germans by the victorious Bolsheviks.

Although ethnic violence would also flow often from both the Red (targeting Jews5, Circassians [who opposed the Bolsheviks for religious reasons], and Germans) and White (targeting Jews) Armies, this was more infrequent owing to the relatively high degree (at least when compared to anarchists and Petrula’s forces) of professionalization within these organizations.

In March 1918, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany and the other Central Powers. The treaty guaranteed the independence of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, several Russian provinces in the Caucuses, and Ukraine. Poland was not mentioned in the treaty, though it was understood that Germany (which had occupied Poland during WWI) would set up a friendly government there as well.

Although pro-German governments sprang up in every area occupied by German troops, most nationalist groups held off on participating in them. Virtually everyone was aware that Germany's long-term chances of winning World War I were slim. The soon-to-be victorious Allies had promised a (likely more expansive) right of self-determination to nations under the Central Powers’ control after the war. This was articulated in American President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, a set of idealistic policy principles intended to lay out the Allies’ war aims and peace terms.

In April 1918, the UPR made an agreement with Germany, accepting military protection in exchange for extremely generous allotments of Ukrainian grain to be shipped to Germany, which was entering a period of massive famine as its situation on the Western Front became more desperate.

The Germans had committed hundreds of thousands of troops to clear Ukraine of Bolshevik soldiers in Operation Faustschlag. Fearing that the Germans (who, although they had secretly funded the Bolshevik Party before the October Revolution with the goal of forcing Russia out of World War I, soon grew tired of the Bolsheviks’ frequent atrocities and attempts to expand the Revolution) simply would not stop their offensive when they reached the Ukrainian-Russian border, Lenin elected to move the Bolshevik capital from Petrograd to Moscow.

The path of various anti-Bolshevik efforts was often determined by their either pro-German or pro-Allies orientation. The Germans could offer immediate security and supplies, desperately needed in the early stages of the Russian Civil War. However, after World War I had ended, the Allies were sure to be extremely hostile to any group that had accepted German help.

Meanwhile, in South Russia, the most serious Russian-led effort against the Bolsheviks was coming into being. Escaping Bykhov Prison was a group of high-profile officers including Generals Lavr Kornilov and Anton Denikin. Kornilov had been the head of the Russian military before the October Revolution. He had a good reputation owing to his World War I combat record and offered a great deal of legitimacy to the infant counterrevolutionary movement.

Meeting Kornilov’s group in the strategically important city of Rostov was General Mikhail Alexeiev, also well-respected, who had been Kornilov’s replacement as the head of the military after the Kornilov Affair. Following the October Revolution, Alexeiev had created the underground Alexeiev Organization to smuggle recruits, intelligence, and supplies out of Bolshevik territory.

Although Kornilov and Alexeiev greatly disliked each other owing to a dispute during the Kornilov Affair (Alexeiev had personally arrested Kornilov over what Kornilov viewed as a disastrous misunderstanding) the two came together in the Cossack-controlled regions of South Russia to create the Volunteer Army and provide a center of Russian resistance to the new Bolshevik dictatorship. It was decided that Kornliov would manage all military affairs while Alexeiev would handle all questions of diplomacy and organization.

The Cossacks are a semi-nomadic and autonomous quasi-ethnic tribal group6 that inhabits the borderlands of Russia. Cossacks are organized into different governing Hosts, each of which is led by a democratically elected Ataman, who supervises his Host’s Rada (parliament). Meetings of several different Cossack Hosts are referred to as Krugs, which are usually only called to resolve a single important issue of mutual interest. Although there were anti-Russian separatist tendencies among the Cossacks, Cossacks typically were also hostile to the Bolsheviks.

Cossacks had a major role in Russia’s military, serving as elite cavalry and border guards. Because of their ethnic and cultural distinctions from the Russian majority, Cossacks were also often employed as internal police and riot control by the Russian government. The visible Cossack presence in suppression of leftist demonstrations (both violent and peaceful) had made Cossacks widely hated by Russian radicals, including the Bolsheviks.

Complicating matters, the Don Cossack government in Rostov, led by Ataman Alexey Kaledin, was mostly ambivalent towards the Volunteer Army. Kaledin was a respected general and politician who had declared martial law in the region at the start of the October Revolution, stopping the local Bolshevik uprising. Many younger Cossacks returning from the frontlines of WWI were thoroughly demoralized by their experiences and viewed the Volunteers (some of whom publicly advocated for reentering the war) with hostility. Furthermore, Alexeiev, already well into old age, was dying of an unknown illness (likely stomach cancer) as he attempted to create a coherent military force from scratch on a budget.

The Kuban Ice March was a series of rolling battles fought by the Volunteer Army after it was forced to flee Rostov following the collapse of the Don Cossack government in the face of a new Red Army advance into the region. Ataman Kaledin, despairing over his inability to rally local Cossack resistance, shot himself rather than be captured by the Bolsheviks.

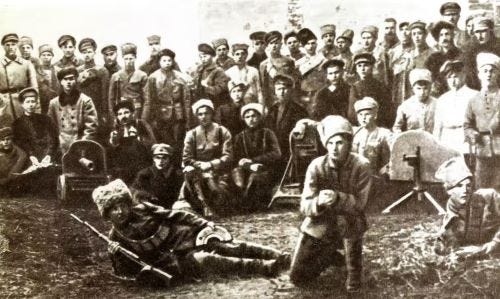

The Volunteer Army marched across the frozen steppe in the dead of winter, pursued by several better-equipped Bolshevik detachments that outnumbered them many times over. The Volunteers, who were mostly former Russian military officers (and therefore had significantly more training, discipline, and experience than the poorly led and organized Red Army detachments they faced), won countless engagements despite regularly being outnumbered 10-to-1.

There was brutal combat nearly every day of the Ice March. The Volunteers suffered catastrophic casualties even in victory. The Bolsheviks often tortured their captives before execution, leaving a trail of mutilated bodies in front of and behind the advancing Volunteer Army.

On the march, the Volunteers linked up with Kuban Cossack forces under the command of General Pokrovsky, a non-Cossack WWI fighter pilot who had proven himself to be a fearless commander and natural tactician. The Kuban Cossacks were very impressed with Pokrovsky after a miraculous victory in which Pokrovsky personally led the rout of a Bolshevik force nearly 25 times the size of his own.

Although Pokrovsky provided much-needed reinforcements and ammunition, he also brought bad news: his detachment, which included the Kuban Cossack Host’s government, had just fled from Ekaterinodar, the Volunteer Army’s planned final destination. The town, which served as the Kuban Cossack capital, had just been seized by the Bolsheviks.

Many other leaders in the future White Army, a term used to describe the loose alliance of all anti-Bolshevik military forces, would complain about Pokrovsky’s frequent looting of the civilian population and tendency to mass execute prisoners and dissidents. Largely unspoken in discussions of Pokrovsky is his desire to become the Ataman of the Kuban Cossacks, which led him to exercise virtually no discipline over the Cossack forces under his command in order to preserve his popularity.

After weeks of intense fighting, the Volunteers finally arrived at Ekaterinodar. The Volunteer Army briefly besieged the city, however, Kornilov was killed when an artillery shell hit his observation post near the contact line. Command of the Volunteers then fell to General Denikin. Denikin was a competent military leader but lacked the political instincts and personal gravitas of Kornilov. Completely demoralized, the Volunteer Army once again retreated back onto the frozen steppe.

Afterwards the Volunteers began a winding, and much more successful, return trip to Don Cossack territory. The column picked up new recruits (the Bolsheviks had become much more unpopular with the Cossacks after the population actually experienced Bolshevik rule) and liberated dozens of Bolshevik-controlled villages along the way.

When the victorious Volunteer Army finally reached the outskirts of Rostov again, they found that the city had been occupied by the advancing German Army.

Although the Germans were not directly hostile to the Volunteers, one of the commonly stated (and widely unpopular) motivations of the Volunteer Army was to retake Russia so that the country could reenter WWI against Germany. General Denikin in particular was known to be an outspoken critic of the Germans. The German garrison implied that the Volunteers would not be welcome in the city and the Volunteers made no attempt to enter.

Even though this tension did not boil over into bloodshed (as Germany’s position on the Western Front declined, its soldiers in the East became reluctant to fight so far from home, particularly against enemies of the hated Bolsheviks) the standoff created many complications for the Volunteers as they struggled to capitalize on their incredible success in the Ice March. The German occupation force greatly restricted the flow of men and supplies to the Volunteer Army.

The returning Volunteers faced another complication: The rise of a new and powerful Don Army. The Don Army consisted of Don Cossacks who had undertaken a fighting retreat, dubbed the Steppe March, similar to that of the Volunteer Army after the fall of Rostov and Ataman Kaledin’s suicide. Although this group was smaller than the Volunteer Army at first, the Don Army had not suffered the Volunteers’ catastrophic casualties while retreating.

On their march, the Don Army encountered and joined forces with a large column of conservative Russian officers led by General Mikhail Drozdovsky.7 After the October Revolution the column had spent months traveling all the way from the frontlines of World War I in Romania, through the chaotic battlefields of Ukraine, and back into Cossack territory, with the ultimate goal of joining the Volunteer Army.

The formidable Cossack-Volunteer combined force retook Novocherkassk, the historical capital of the Don Cossack Host (nearby Rostov had a larger population and more commercial activity, but also contained significant numbers of non-Cossacks), from the Bolsheviks. Public excitement from this victory led the Don Cossacks to declare their independence from Russia in the form of the Don Republic. This new Cossack nation was to be led by deceased Ataman Kaledin’s newly elected successor: The brilliant but extremely ambitious Ataman Pyotr Krasnov.

Krasnov had led the loyalist detachment outside of Petrograd that Kerensky had joined with shortly after the October Revolution. After separating from Kerensky, Krasnov had been captured by the Bolsheviks but, owing to his relative obscurity at the time, was released from prison by Trotsky after Krasnov signed a pledge that he would not resist the Bolsheviks. These pledges were relatively commonplace for captured loyalist soldiers at the time as the Bolsheviks did not have the facilities or capacity to take huge amounts of prisoners, and, at least immediately after the Revolution, they were conscious that mass executions might alienate the public. Krasnov immediately broke this pledge and headed to South Russia to join with Don Cossack forces there.

Although Krasnov deeply hated the Bolsheviks, he did not share Denikin’s hostility to Germany and immediately sought out German help. The Germans provided the Don Army with stores of weapons and ammunition that dwarfed those of the Volunteers. Furthermore, the local Cossack Hosts called a Krug and agreed to implement conscription among the Cossacks, swelling the Don Army’s manpower to many times the size of the Volunteer Army’s.

It’s likely that Krasnov did not actually want long-term independence from Russia. However, he was well-aware that the existence of an independent, larger, and better supplied Don Cossack force left him in a very strong bargaining position when dealing with the Volunteer Army or whatever other group might claim to represent of all of Russia after the Bolsheviks fell.

Unwilling to fight the Germans and conscious of the fact that the Don Cossacks were rallying behind Krasnov, Denikin decided to march the exhausted Volunteer Army back to the Kuban and liberate the cities in that region still under Bolshevik control. The Kuban Cossacks, Denikin hoped, would be less easily seduced by the prospect of independence and German aid.

Just months after the stunning success of the October Revolution, the Bolshevik position in Russia seemed more precarious than ever before. Lenin had been forced to surrender huge swaths of the empire he had just seized to the German Army, which seemed as though it could easily advance into the Bolshevik heartland if it chose to. Furthermore, Russian counterrevolutionaries had finally organized and struck decisive blows against the surprisingly weak Red Army, which, in spite of its huge size advantage, was paralyzed by incompetence and poor leadership.

Despite these setbacks for the Bolsheviks, the situation for the combined White Armies was also far less stable than their recent military successes might suggest. Major political cracks between the various anti-Bolshevik forces had already begun to show. The counterrevolutionaries couldn’t agree on what they were fighting for, much less how to achieve it. These fissures would only deepen over time.

Part IV: Ukraine and Finland/The Revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion/Regicide

By mid-1918, the Revolution was in dire straits.

Although Bolshevik Party Chairman Vladimir Lenin had successfully overthrown the weak Russian Provisional Government just months earlier in the October Revolution, serious threats to the new Soviet regime were emerging from all corners.

The first major setback for the Bolsheviks came in Finland. Finland had declared its independence from Russia shortly after the October Revolution. Although the Bolsheviks had formally recognized Finland’s independence soon after, this was merely a ploy to avoid a premature conflict with Finland’s conservative government.

The Bolsheviks organized labor unrest in Finland’s major cities. Strikes, sabotage, and work stoppages threatened to topple the already fragile Finnish economy (seriously disrupted by the chaos that had overtaken Russia, its biggest trading partner). Political street violence became commonplace and it seemed clear to everyone that a larger Bolshevik uprising would follow soon. The White Guard, a conservative militia that at first acted as law enforcement (the old Russian Imperial police had dissolved following the February Revolution, leading to months of anarchy), was hastily assembled.

Finland’s conservative government appointed Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim to lead the counterrevolution. Mannerheim had spent most of his life as a cavalry officer in the Russian military, including time as an explorer and diplomat. Although Finns were exempt from conscription by Russia owing to Finland’s status as a Grand Duchy, they could volunteer for service with Russian forces.

When the local Bolshevik uprising finally arrived in January 1918, the Reds quickly captured most major cities in Finland and assembled an army that greatly outnumbered the White Guard. However, the Whites had the benefit of a pre-planned structure to resist the revolution. Mannerheim had been given supreme executive authority by mutual agreement of all Finland’s conservative factions.

This unified command greatly benefitted the Whites during the Finnish Civil War, allowing them to avoid the infighting and indecision that paralyzed other counterrevolutionary movements. The Finnish Whites successfully resisted the initial offensive from the Finnish Reds, who were openly supported with weapons and troops by the Russian Bolsheviks. Although the Reds had a larger and better-equipped force, they suffered from poor training and leadership.

By March 1918 the Finnish Whites had introduced conscription, allowing them to achieve numerical parity with the Reds, and launched a major counterattack. After a decisive victory at the bloody Battle of Tampere, Mannerheim had planned to march on Helsinki, the nation’s capital. However, Mannerheim’s plans were complicated by a large German military intervention on the side of the Finnish Whites.

Against Mannerheim’s orders, members of the Finnish government requested that the German Army send troops to recapture Helsinki, which had been seized by the Reds during their initial uprising. Although Mannerheim wasn’t hostile to Germany, he understood that open German military intervention could undermine the Whites’ claims that they were the true representatives of the will of the Finnish people. Although the Bolsheviks were internationalists and accepted help from other nations freely, they always accused their enemies of being mere puppets of foreign powers.

Furthermore, it was also obvious to nearly everyone that Germany was going to lose World War I at that point. Taking on Germany (which led the Central Powers in the conflict) as a partner could create serious complications for Finland when dealing with the sure-to-be victorious Allies after the war.

Over Mannerheim’s objections, the newly invited German troops staged successful landings at Helsinki and several other cities along the Baltic Sea, sending the Finnish Reds into a panicked retreat. Mannerheim’s army pursued the retreating Reds and destroyed their largest remaining military formation at the Battle of Viipuri. The Finnish Civil War was effectively over in May 1918.

Bolshevik atrocities in Russia were well known by that point and there was great hatred of the Finnish Reds for the months of chaos that had preceded their uprising at behest of Bolshevik Russia. The aftermath of virtually every major battle of the Finnish Civil War was marked by mass executions of Red prisoners by the Whites. Tens of thousands of Red prisoners of war were also herded into prison camps with very poor conditions, where thousands died from disease or starvation.

Although the Finnish Reds committed many atrocities of their own during the war, the Finnish White Terror, as these killings would become known, would often be cited among justifications for the Red Terror, the official Bolshevik policy of political repression and mass execution adopted later that year.

The victory of the Finnish Whites also triggered the first major Allied intervention into the Russian civil conflict. The strategically important port of Murmansk in the Arctic Circle, near the Finnish border, was home to massive stockpiles of Allied war material from the time of Russia's participation in World War I. The Allies did not formally recognize the Bolshevik government, and a tense standoff emerged between the Bolsheviks and the nearby British North Russian Squadron, who refused to allow the Bolsheviks to access these supplies.

The apparent pro-German orientation of the victorious Finns (who regularly raided Bolshevik territory after the Finnish Civil War) alarmed the Allies, who were concerned that the Bolsheviks would fall too quickly and be replaced by a pro-German Russian government. Lenin, seeing that the tiny local Red Army force could not hope to resist the Finns, invited the Allies to occupy Murmansk. In March 1918 several thousand British and American troops entered the city, easily driving off the Finns with little fighting.

The Bolsheviks quickly soured on the Allied presence, but the Allies simply refused to leave—citing their obligations to their (now deposed) former partner the Russian Provisional Government. Lenin, already concerned about the prospect of a German invasion, could not risk entering into a direct conflict with the Allies and was forced to hold his tongue.

In Ukraine, the situation for the Bolsheviks had become even more grim. Although the nationalist Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) government had been pushed out of the capital Kiev by the Bolsheviks (owing to an ill-advised decision by the UPR to betray the pro-Russian military officers whom they had allied with to suppress an earlier Bolshevik uprising), the UPR had signed an agreement with the advancing German Army: The Germans would guarantee the independence of Ukraine (in practice, to militarily occupy the entire country) in exchange for very generous allotments of grain to be shipped from Ukraine to Germany.

The Germans easily overcame the local Bolsheviks and took control of most strategic points in the country. Lenin, terrified by the recently revealed weakness of his Red Army (which had suffered a seemingly unending string of devastating defeats both in and outside of Russia), encouraged Ukrainians not to resist the German occupiers out of fear that renewed fighting might provoke the Germans to advance into Russia proper and topple the Bolshevik government once and for all.

The UPR was dominated by socialists of various kinds. Its main focus before the Revolution had been land policy.

Russia (of which Ukraine had been a formal part for centuries) had a special class of peasants called serfs who were tied to the land that they worked, controlled by the state or noblemen. Although Czar Alexander II had abolished serfdom in 1861, the state land that had been worked by serfs wasn't given to the serfs to be owned in individual plots. Instead, it was distributed to village communes.

These communes offered none of the incentives of private ownership and distribution of land, surplus, and other essentials of agricultural life was often very unfair. Serfs who had belonged to noblemen (a more common arrangement in Ukraine) were in an equally unfavorable position, often forced into exploitive sharecropping or tenant farmer agreements by large landowners.

The land situation left nearly everyone unsatisfied. For decades, violent radical movements had been able to get widespread public support by proposing any changes at all to this system.

Once nominally back in power (Ukraine outside of German occupation remained in a state of anarchy), the UPR adopted a strangely radical position: banning private land ownership and announcing impending mass farm collectivization. These were policies that the Bolsheviks had been pushing for all along.