In 1911 a socialist was almost elected mayor of Los Angeles but he lost after ACLU hero Clarence Darrow was caught bribing jurors to free terrorists who murdered 21 people

This story is nuts

Reposting the unified (and slightly revised) version of this originally 3-part article in light of the recent New York City mayoral primary. None of our problems are new! We are fighting very old forces and eternal types. You should be able to use the Substack App’s (very good) text-to-speech program to listen to this.

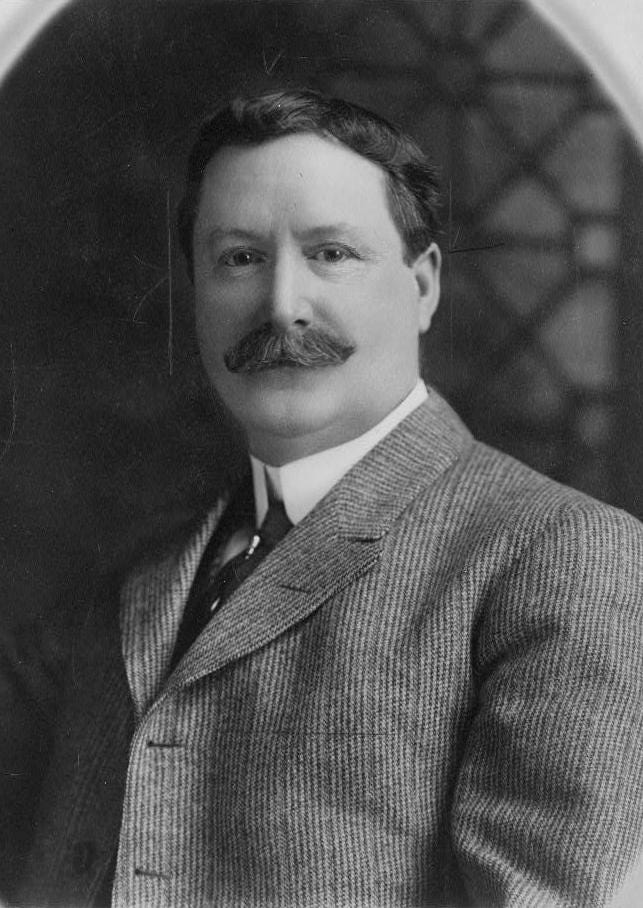

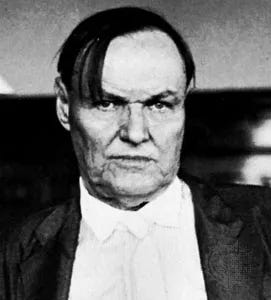

Clarence Darrow is one of the most famous lawyers in American history. Millions have seen the film Inherent the Wind (1960) dramatizing the Scopes Monkey Trial in which Darrow famously argued against a Tennessee law that banned the teaching of evolution in schools.

Darrow’s views and methods were extremely influential. He defended people considered indefensible in his time: millionaire thrill killers, assassins, blacks accused of raping white women, and even terrorist bombers. His clients were to be given every benefit of the doubt. Rather than focusing solely on the facts or the evidence, Darrow placed crimes in the larger context of popular progressive causes of his day.

Darrow was a competent and eloquent trial lawyer. His closing arguments lasted for hours, sometimes days. Of the fifty accused murderers he defended, only one was ever executed: Patrick Eugene Prendergast, a deranged man who shot the Mayor of Chicago to death. Darrow attempted to have Prendergast found not guilty on the grounds of mental insanity but failed. He was hanged on July 13, 1894.

Darrow was known as a lawyer who could pull a rabbit out of a hat. His clients could be unambiguously guilty, yet Darrow would use every trick in the book (and a few outside of it) to have them acquitted on any grounds. His commitment was ideological. Darrow’s parents were both lifelong progressive activists. Darrow was a patron of liberal causes, an influential figure in Chicago machine politics, and a fighter who could always get things done.

It was this reputation that eventually led Darrow to be hired to defend the McNamara brothers, J.J. and J.B. The brothers were organizers for the International Association of Bridge and Structural Iron Workers (IW), a prominent labor union in the Los Angeles area. Although the union had had some successes since it was created in 1896, by 1910 they had been ejected from many foundries and mills.

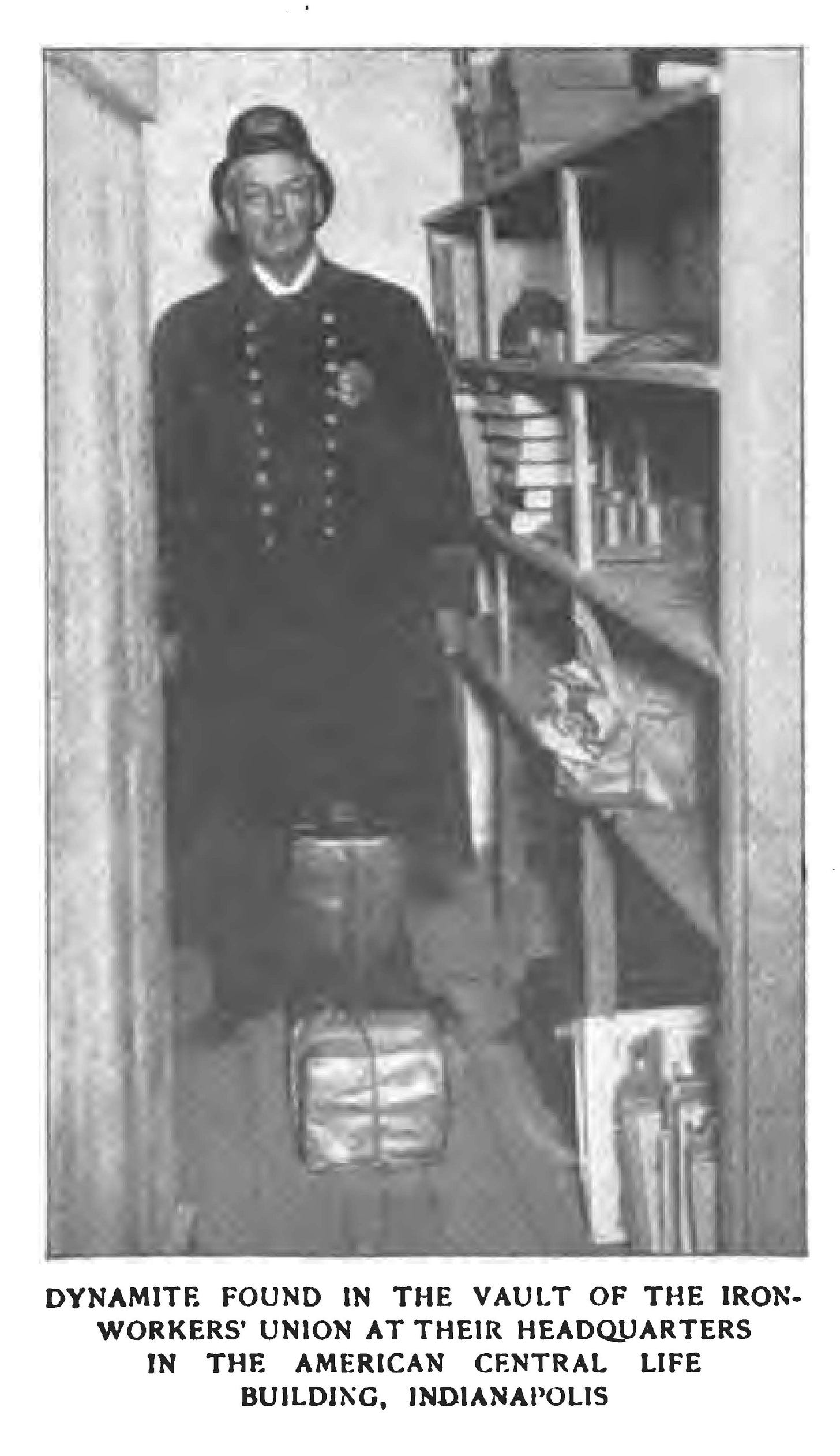

In response to these setbacks, the IW began a terrorist bombing campaign. Between 1906 and 1911, the union and its affiliates blew up 110 iron works across the country using dynamite. Although there were hundreds of bombings organized by the union, the damage was usually slight and very few were injured.

One of the biggest critics of unions during this period was the L.A. Times. The newspaper’s publisher, Harrison Gray Otis, was an archconservative who wanted to rid the city of Los Angeles of all unions. By 1910, the IW was one of the last strong unions left in the city.

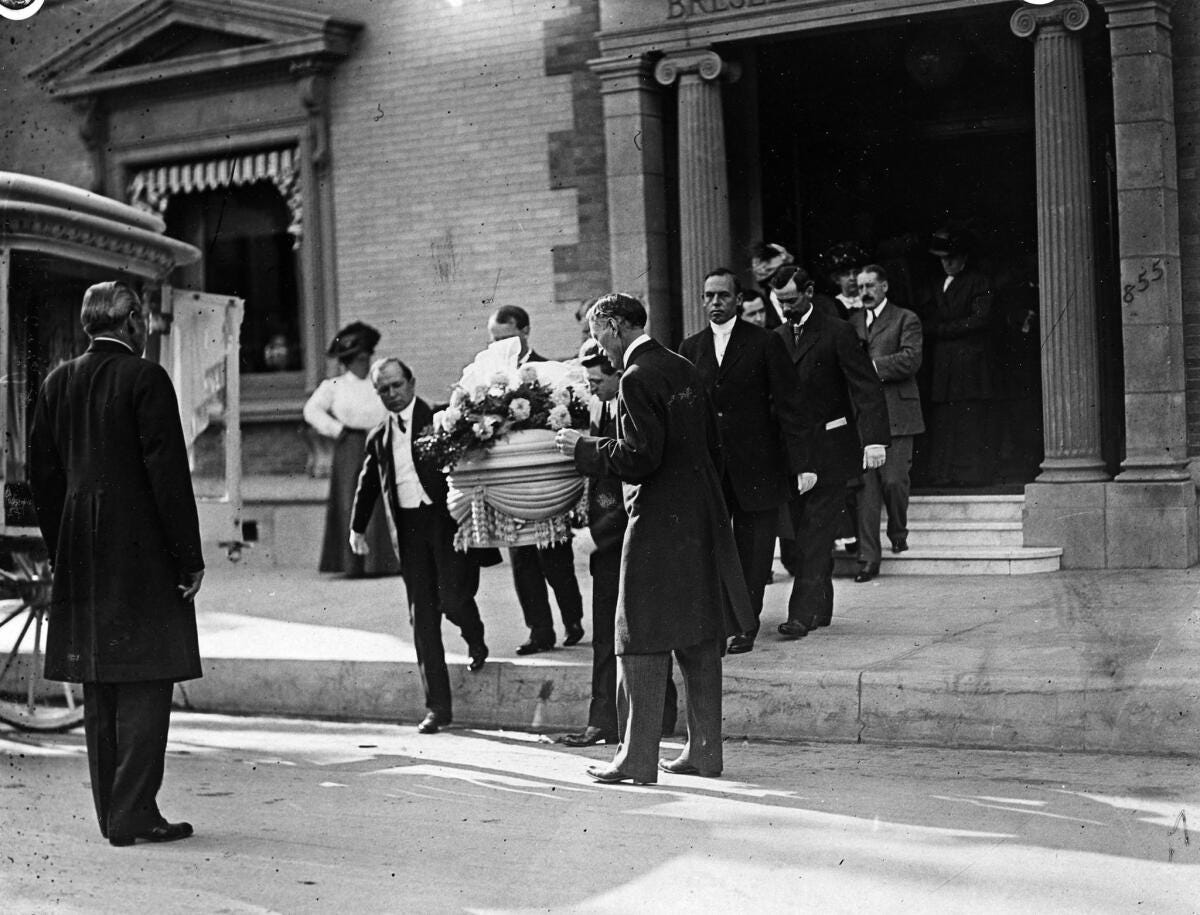

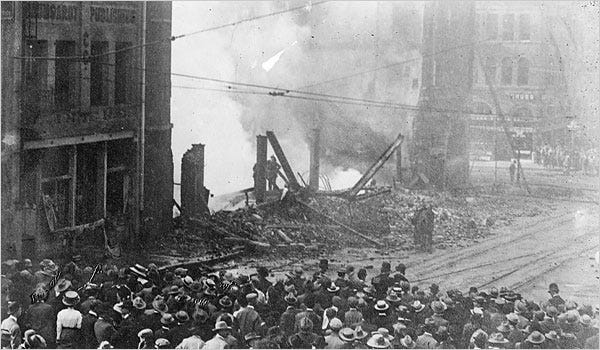

At 1 AM on September 30, 1910, a bomb exploded outside the L.A. Times building. The bomb was positioned next to several exterior gas lines, multiplying its explosive effect exponentially. Making matters worse, the L.A. Times had a nearby annex where thousands of gallons of highly flammable ink were stored. The bomb and ensuing fire devastated the building. Of the 115 people inside at the time of the explosion (mostly low-level workers trying to finish an extra edition of the paper overnight), 21 died. Most deaths were from the fire rather than the explosion. The bodies were horribly disfigured.

Two more bombs were discovered across the city. The first was outside of L.A. Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis’s house, the other was near the home of the secretary of a local business association. The bomb outside of Otis’s house was discovered before it detonated and the intended victims were able to evacuate. Detectives attempted to defuse the first bomb before it blew up but failed and barely escaped with their lives. The second bomb malfunctioned and police were able to recover it intact.

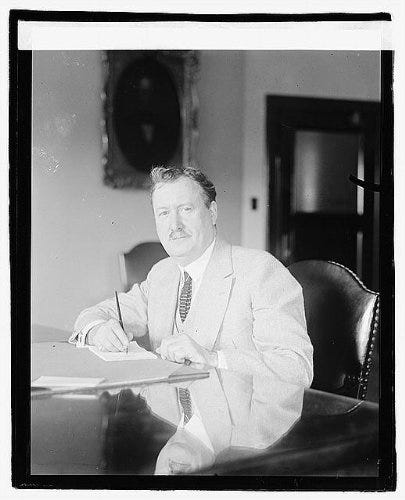

Although Los Angeles had a very capable police force by standards of the time, it’s investigative service was still primitive. L.A. Mayor George Alexander decided to hire William J. Burns, America’s leading private detective, to bring the bombers to justice.

Burns was a former Secret Service agent who launched his own detective agency. He had already solved several high profile cases, including stopping an assassination attempt on the British ambassador. He was known for his integrity and had been widely praised by labor leaders for unravelling a series of title frauds committed by business interests in the Pacific Northwest. Burns was already investigating a nationwide series of bombings similar to the L.A. Times attack on behalf of the National Erector Association and maintained an extensive network of contacts within America’s labor underworld.

After months of investigation, Burns infiltrated a union hunting retreat undercover and was able to extract a drunken confession from J.J. McNamara. Burns learned that J.B. had planted the bombs on J.J.’s orders. He also identified Ortie McManigal as another bomber employed by the union.

When Burns had J.B. and McManigal arrested, police discovered a small arsenal of guns, suppressors, and bombmaking material in their suitcases. Several witnesses identified J.B. as a man seen near the building before the bombing. Other witnesses were able to identify J.B. and McManigal as the men who had bought the unique explosive mixture used in the bombings under false names.

Faced with overwhelming evidence, McManigal was persuaded by Burns to make a full confession. Although McManigal hadn’t been involved in the L.A. Times bombing, he knew all the details of the plan from the brothers. The bombs McManigal had set during earlier incidents hadn’t killed or injured anyone, so he was eager to take a deal.

The McNamara brothers did little to help their case after their arrest. J.B. stated to reporters as he was being extradited back to California that “This train will either be wrecked or blown up before we reach Los Angeles. I have eluded my captors enough to get word to my friends to see that we do not get to the coast alive.” It was difficult to distinguish the McNamaras from ordinary gangsters.

The reaction from the American Left at the time was immediate and unanimous: The McNamara brothers had been framed and McManigal had been bribed to give a false confession.

The State Labor Federation of California sent a committee of “experts” down to the crime scene who issued a report saying that there was no evidence that explosives had been used at all. Rather, they claimed, the “bombing” was actually an industrial accident stemming from a gas leak, cynically manipulated by business interests to discredit organized labor. Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs claimed that there had been bombs, but they had been set by business leaders as a false flag.

To defend the McNamara brothers, labor leaders hired Clarence Darrow. At the time Darrow was regarded as America’s most brilliant lawyer after he had successfully defended union boss “Big Bill” Haywood from murder charges in 1907.

Haywood was an eccentric and bombastic figure who openly advocated for violence against the opponents of unions. The former governor of Idaho, who had declared martial law in an effort to stop union violence during his term, had been assassinated at his home using concealed explosives.

The bomber was eventually captured but underwent a religious epiphany and named Haywood as the man who had ordered the killing. The bomber confessed to numerous other murders and detailed years of violence at the behest of his union employers.

The evidence against Haywood was overwhelming and most legal journalists covering the trial thought that he would be convicted of murder. However, after Darrow gave a lengthy and innovative closing argument (still reprinted today) that emphasized the larger social justice movement rather than the evidence, Haywood was acquitted. Prominent far-left lawyer Erskine Wood, a friend of Darrow, suggested that Darrow had used “crooked methods” to secure the acquittal.

The New York Times reporter at the trial said of Darrow’s closing:

He was a master of invective, vituperation, denunciative humor, pathos, and all the other arts of the orator, except argument. It was ostensibly a plea for the life of Haywood, but, in fact, it was an address, not to twelve jurors in front of him, but to his Socialist clientele.

After being acquitted, Haywood skipped bail and defected to the Soviet Union following an arrest for violating the Espionage Act of 1917. He died several years later in Russia due to a stroke brought on by alcoholism and diabetes.

Darrow demanded a fee of $50,000, the equivalent of $1.6 million today, to defend the McNamara brothers. Darrow knew that his clients were guilty before the trial began.

United Press union organizer Ernest Stout reported on a meeting with Darrow in a memo, stating that “[Darrow] would not defend the McNamaras or McManigal because Burns had absolute proof of their guilt.” Although Darrow first told Stout he wouldn’t take on such a weak case, he eventually agreed to defend the bombers.

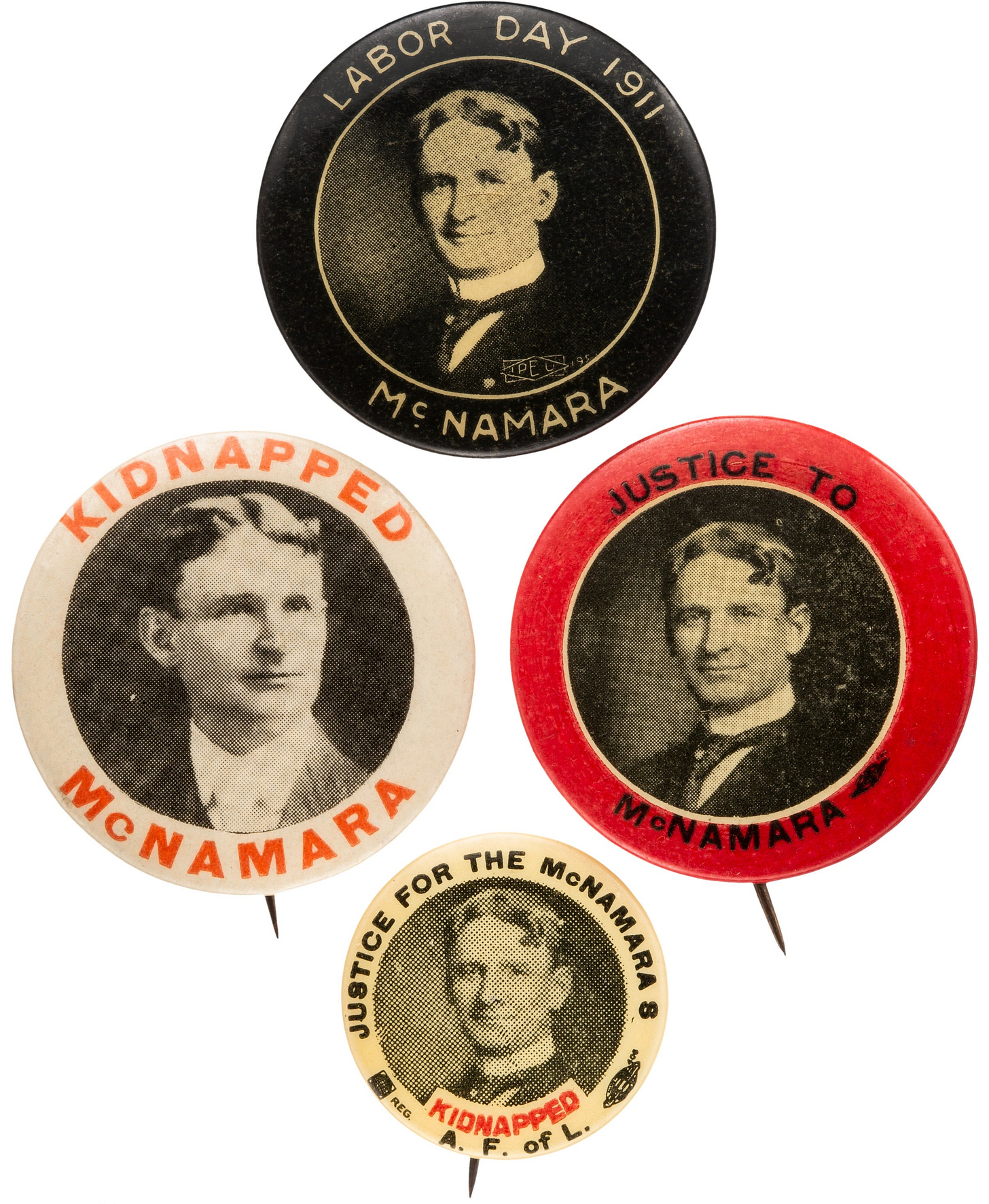

The labor movement embarked on a massive fundraising campaign to fuel the defense. American Federation of Labor (AFL) head Samuel Gompers asked every union in his network to require each of its members contribute $0.25 to the defense fund. A film was made, “J. J. McNamara—A Martyr to His Cause,” and roughly 50,000 tickets were sold. A parade of about 35,000 union workers and labor activists marched through downtown Los Angeles to support the McNamaras’ innocence. Pins were also sold to raise money, with their text usually pushing the idea that Burns had actually kidnapped the McNamaras during their arrest.

The brothers’ defense was funded almost entirely through small donations from workers who didn’t have much, but believed Darrow and labor leaders when they said the McNamaras had been framed. Darrow hoped to eventually raise as much as $350,000 (the equivalent of $11,300,000 today). He would need it, too, because defending clients who were so obviously guilty had costs.

One of the witnesses, the man who sold the explosives used in the bombing to J.B., was approached by one of Darrow’s agents. The agent offered the witness a bribe if he would change his description of the man who he had sold the explosives to at trial. Darrow’s agent told the witness that, if he didn’t accept the bribe, he would be murdered.

Darrow personally tried to bribe one of Burns’s top detectives to provide insider information on the case against the McNamaras. The detective pretended to accept the bribe, secretly turned the money over to Los Angeles prosecutors, and then began falsely claiming to Darrow that various labor organizers and trusted confidants were actually spies for Burns in order to sow confusion. Darrow didn’t discover the deception until much later.

Darrow was constantly tailed by detectives. By this point, Burns and prosecutors were well aware that beneath Darrow’s “crusader for justice” persona was actually a deeply unethical and cynical activist who was willing to do anything to get his clients off the hook whether they were guilty or not. On September 1, police observed Darrow take an uncashed check to the office of San Francisco labor leader Olaf Tveitmoe. Tveitmoe deposited Darrow’s check, wrote a check of his own at a nearby bank, then cashed that check for $10,000 cash ($323,000 today).

The defense of the McNamaras got off to a bad start. Shortly after taking the case, Darrow had publicly endorsed the “gas leak” theory to explain why the L.A. Times building exploded. Darrow paid thousands of dollars to construct a miniature model of the building so that it could be blown up with gas and prove that the source of the explosion couldn’t have been dynamite. Although the test was conducted several times, it actually showed that the explosion was almost certainly caused by dynamite.

Making matters worse for Darrow, a hotel clerk who could disprove J.B.’s alibi was discovered. Although Darrow’s agents had persuaded the clerk to leave town without testifying, Burn’s detectives managed to track him down in Chicago and convince him to return to Los Angeles to testify for the prosecution.

As the trial entered jury selection, Darrow was desperate. He knew his clients were guilty but he had staked his public reputation on their innocence. Furthermore, the real clients who were bankrolling him, Samuel Gompers and the AFL, appeared to have no idea that McNamaras were actually behind the bombing. As Darrow scrambled to salvage his case, the check he had given to Tvietmoe would take on enormous importance, both for the McNamaras and Darrow himself.

Part II

Burns’s detectives and local police maintained a close watch on Darrow and his agents. Everyone knew that Darrow was willing to operate well outside the law. His behavior went beyond wanting his clients to have a fair trial. He wanted his clients to be acquitted of terrorist bombings because, as his later statements revealed, he supported terrorist bombings.

This barely concealed support for terrorism among mainstream leftists, channeled through the L.A. Times bombing case, was not unique to Darrow.

The left-leaning San Francisco Bulletin stated:

To the dispossessed in the rear of the courtroom, McNamara is a persecuted man, a martyr; Darrow is a hero; the District Attorney a very devil, the judge a monster. Among them are many potential bomb throwers. If McNamara’s life goes out on the scaffold at San Quentin, a white flare of hate will sweep out over the land. It will burn hottest where society’s outcasts gather in squalid rooms and make bombs, dreaming meanwhile of revolution. Perhaps even the judge wonders if there isn’t a better way.

The trial would not come down to the evidence. The evidence only went one way: Towards the McNamaras’ guilt. Instead, it would turn on who served on the jury. Could jurors be found who were OK with letting murderers walk free?

Bert Franklin was hired as Darrow’s chief “researcher” to handle the investigation of potential jurors for the defense. Franklin was a former L.A. County Sherriff’s deputy and US Marshal who opened his own private detective agency.

As the jury pool narrowed, Franklin targeted one of the potential jurors, Robert Bain. Bain was a proud 70 year old Civil War veteran who regularly played the drum in Memorial Day parades. Although Bain was a respected member of his community, after some bad investments he was desperate for cash.

Franklin first approached Bain’s wife, offering to help the family pay off their mortgage if he would vote to acquit the McNamaras in the event he became a juror.

Bain’s wife begged Bain to accept the deal and, after some reluctance, he agreed. Bain refused to even look at the money after receiving it from Franklin, saying “After seventy years in which I served my country, my honor is gone.” Bain was selected as a juror several days later.

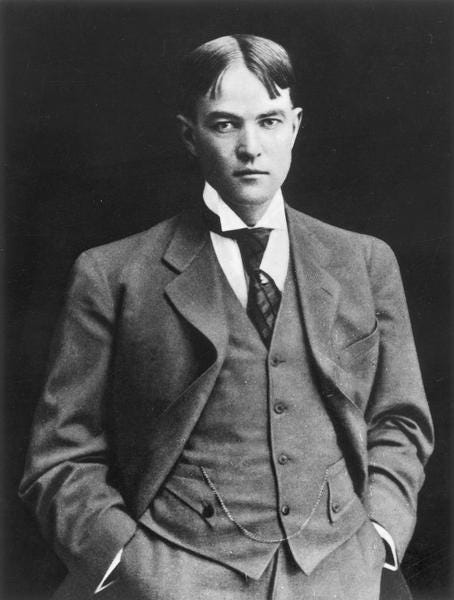

Although the evidence side of the case looked more and more hopeless for Darrow every day, the political side of the case seemed to improve. Darrow added mayoral candidate Job Harriman to the defense team. Harriman was a vocal critic of organized religion and member of the Socialist Party of America.

Although Los Angeles at the time was known as a conservative town, the openly socialist Harriman had surprised all political observers by coming in first during the 1911 Los Angeles mayoral primary. Harriman received an impressive 44% of the vote compared to incumbent mayor George Alexander’s 36%.

As Harriman worked for the defense, he was also campaigning against Alexander in the run-off election. Harriman often claimed that the McNamaras were framed as part of a conspiracy to prevent him from being elected mayor. It’s likely Harriman’s overperformance in the primary was directly tied to the media campaign surrounding the McNamaras’ defense.

Darrow hoped to delay the trial long enough for Harriman to win the election, which would allow him to manipulate the judicial process through control of police and other city agencies.

Further bolstering the political side of Darrow’s case was that the District Attorney’s office in Indianapolis, where the McNamaras had hatched much of their bombing scheme, had been taken over by liberals.

Although conservative local police had seized many incriminating files and letters from the McNamaras and their associates, the new liberal Indianapolis District Attorney refused to transfer the documents to Los Angeles prosecutors to help make the case against the McNamaras.

Liberal prosecutors refused to bring charges against union officials for the many crimes detailed in the evidence. In fact, the Indianapolis District Attorney began the process of returning the gathered evidence to union officials, knowing that the documents would be destroyed or altered. It was only a direct appeal to President Taft by Otis, the L.A. Times publisher who had almost been killed by a bomb set at his house by the McNamaras, that prompted federal officials to sweep in, seize the remaining documents from the Indianapolis District Attorney, and share them with Los Angeles prosecutors.

As this was going on, jury selection in Los Angeles continued. Darrow hoped to draw out the jury selection process as long as possible in order to ensure that the Socialist Part could win the upcoming election. There were frequent rumors, never proven one way or another, that Darrow began using large amounts of defense funds to support Harriman’s cash-strapped campaign.

Darrow turned the jury selection process into a circus. He maintained that the case was not about a bombing or murder, but rather the larger “war” between labor and capital, the national movement for “social justice.” Darrow asked pointed and inflammatory questions about prospective jurors’ religious and political views. It was a performance for the press and an attempt to poison the well before the evidence against his clients was discussed.

On November 7, 1911, one of J.J. McNamara’s best friends, who had participated in several earlier union bombing plots, agreed to testify against the brothers. Although the case was bad before, the evidence gathered by Burns and his detectives was simply bulletproof. It became impossible for anyone but the most hopelessly indoctrinated or naïve to accept the McNamaras’ innocence. Everyone involved with the McNamaras knew that they would be going down for something, somewhere.

Darrow began exploring options for a plea deal. Business leaders had had enough of terrorist bombings, they wanted blood. However, they also wanted to defeat Harriman in the election and prevent the socialists from taking control of city government.

Everyone knew that a guilty plea would destroy Harriman’s chances in the election because Harriman had campaigned on the brothers’ innocence, repeatedly claiming that the bombing was actually a conspiracy by big business. If the McNameras confessed, it would totally discredit the labor movement both in Los Angeles and the rest of the country. Harriman was kept in the dark about the plan to throw him under the bus.

Far left journalist Lincoln Steffens, Darrow’s friend, acted as an intermediary between the defense and Los Angeles business interests, hoping to work out a deal that would at least spare J.J., against whom the evidence was more circumstantial, from prison. Sweetening the pot for business interests was the offer that the AFL and other unions would end their ongoing and widening strikes in the Los Angeles area in exchange for light sentences for the brothers.

Los Angeles prosecutors refused to accept a deal that didn’t involve jail for both men. They had both brothers dead to rights for the murders. Law enforcement was tired of the brazen criminality from labor mafia organizations. It was only a matter of time before another mass casualty event occurred. The brothers themselves were also unwilling to save one brother by condemning the other.

The McNamaras knew that admitting to the bombing would devastate the very powerful San Francisco unions that they frequently worked with. This risk alone made it worth it for them to risk trial. Even if they were found guilty, they could always create a similar “falsely convicted” narrative like those built for other (definitely guilty) heroes of the far left around that time. Who knows? They might even be pardoned eventually.

As Darrow prepared for trial, Franklin set his sights on another prospective juror to bribe: George Lockwood, a former law enforcement official who Franklin had worked with when Franklin was a deputy sheriff.

Lockwood was living in semi-retirement on his ranch on the outskirts of town when Franklin approached him on November 14. Lockwood was outraged by the suggestion that he would take a bribe and immediately reported the offer to a friend at the L.A. District Attorney’s office. Rather than take immediate action, the District Attorney, John D. Fredericks, told Lockwood to play along and accept the money if Franklin approached him again.

When Lockwood’s name was drawn as one of the final candidates to be considered for jury duty, Franklin showed back up at Lockwood’s ranch. Franklin promised Lockwood $4,000 (the equivalent of $130,000 today) if he would vote to acquit the McNamaras in the event he ended up on the jury. There would be an initial payment of $500 ($16,250) cash and then the rest of the money would be delivered after the trial.

Following instructions from the L.A. District Attorney, Lockwood accepted the bribe and then demanded that the remainder of the money be held by a mutual friend to guarantee that he would be paid after trial. They all agreed to meet in downtown L.A. to make the handoff.

On November 28, 1911, Lockwood, Franklin, and the intermediary met at the predetermined spot and exchange the money. The $4,000 was all there as agreed. However, Franklin soon noticed that they were being watched: at least 6 LAPD detectives were surveying the scene. Not realizing that he had been set up yet, Franklin told the group to start walking down the street. As they began to move away from the detectives, Franklin spotted Clarence Darrow himself walking straight towards the group.

Franklin said “Wait a minute, I want to speak to this man,” as he approached Darrow, but before they could say anything to each other they were intercepted by LAPD Detective Samuel Browne. Browne separated the men, who were only a few feet apart, and placed Franklin under arrest. Darrow was allowed to leave the scene and his presence wasn’t widely known until weeks after the arrest.

The bribery charges made national headlines. Darrow quietly bailed out Franklin using $10,000 cash (about $323,000 today), a large portion of the remaining defense funds. He took pains to conceal the fact that he had been spotted at the scene. Prosecutors had made no mention of it to the press, they had plans for Darrow.

Darrow publicly denied that any defense funds had gone towards bribery, a shameless lie. Although he had long considered the case against the McNamaras to be hopeless, Darrow now faced the prospect of charges of his own.

In late December, Darrow drunkenly visited one of his mistresses and put a revolver on her table. “Molly,” he said, “I’m going to kill myself. They’re going to indict me for bribery in the McNamara case. I can’t stand the disgrace.” He then began to sob.

Part III

“Abstract love of humanity is nearly always love of self.”

―Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Idiot

Darrow understood immediately that the McNamaras’ case, which was always a longshot, was now hopeless. The public was enraged by news of the attempted bribery. They had been told by Darrow and labor leaders that it was the prosecution, not the defense, that had been engaged in corruption.

Bribing a juror was the sort of brazen dishonesty that removed any illusion of a moral high ground that the defense could appeal to: The McNamaras weren’t heroes, they were gangsters who killed without remorse. Darrow wasn’t a crusader for truth and justice, he was cynical activist willing to achieve his objectives (freeing murderers from jail) by any means necessary.

The only move on Darrow’s mind was a plea deal. If he could somehow get the prosecution to accept a deal before the election, which would almost certainly go against Harriman as soon as the bribery story became widely known, Darrow might be able to avoid the death penalty for at least one of the brothers. Offering the prosecution an easy way out of the case might also spare Darrow himself from criminal charges. For reasons that must have driven Darrow mad, prosecutors had still not publicly announced that Darrow was caught at the scene of the exchange.

Harriman was kept out of discussions of a plea deal despite being on the defense team. It was suspected by many of Darrow’s critics on the Left after the fact that Darrow didn’t want to risk the chance that Harriman would convince them to take the case to trial. Darrow would admit this himself in his autobiography.

The decision to take a guilty plea was widely unpopular among organized labor insiders on the defense team. Although the McNamaras might be convicted, they could always claim they had been framed. Over time, a fake innocence narrative might develop that would lead to them being pardoned or having their sentences commuted, as happened to many leftist terrorists during this period. There was no chance of this sort of revisionist narrative taking hold if the men pled guilty.

What ultimately persuaded the men was the suggestion that their guilty pleas might spare San Francisco labor leaders, who conspired with them on the bombings, from further law enforcement scrutiny. The McNamara brothers pled guilty on December 1, 1911 and claimed full responsibility for the bombings and the murders.

The reaction to the guilty plea was widespread shock. Socialists and labor activists openly wept in the courtroom and at public gatherings. According to the L.A. Times, thousands of pins supporting the McNamaras and Harriman’s mayoral campaign littered the sidewalks all over the city. Supporters tore off their pins in disgust upon hearing the news that the brothers had been guilty the whole time.

The McNamaras’ family members continued to insist that the brothers were innocent, claiming that the guilty pleas were made under duress. Harriman was decisively defeated in the mayoral election that week by a 2-to-1 margin. He hadn’t been notified of the defense negotiations and only learned that the McNamaras had pled guilty through the newspapers.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt sent William J. Burns, the private detective who had unraveled the case and captured the McNamaras, a note of personal congratulations: “All good American citizens feel that they owe you a debt of gratitude for your signal service to American citizenship.” Burns, who had been the subject of a huge smear campaign by labor unions, which claimed Burns had framed and kidnapped the brothers, said “I have gained a great personal vindication.”

As the public gradually recovered from the shock of the guilty plea, they began looking for someone to blame and gradually settled on Darrow. Slowly but surely, people began to wonder aloud why a man who had so adamant that the brothers were framed would suddenly admit they were guilty, especially on the eve of an election where the Socialists probably would have won otherwise.

Darrow’s duplicitous behavior burnt his reputation with the labor unions. Samuel Gompers, the head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), had coordinated fundraising for the case and staked his public reputation on the McNamara’s innocence. He seemed to have genuinely believed that they were framed and was stunned to find out that they had actually committed the bombing, a fact that Darrow knew all along. No effort was made to notify him of the impending guilty plea.

Darrow also made the deeply unethical (and possibly criminal) decision to urgently request $10,000 (about $323,000 today) from the McNamaras’ defense committee, which was unaware of the plan to plead guilty, two days before the brothers actually entered their guilty plea. It’s not clear where the money that Darrow requested went. It definitely didn’t go to their defense. It’s likely that Darrow was simply emptying out the brothers’ accounts to pay himself. Gompers said to reporters: “We have been cruelly deceived.” Adding insult to injury, Darrow publicly stated that “I never told Samuel Gompers or anyone else that J.B. McNamara was innocent.” He was comfortable lying to everyone about everything.

News soon reached Darrow that, on top of being caught in the act bribing juror George Lockwood, the other juror he had bribed, Robert Bain, had decided to confess and was cooperating with the District Attorney.

Darrow knew charges for bribery would be coming, but he didn’t know when or how. He turned on one of his lead investigators, Larry Sullivan, who Darrow had been using to threaten prosecution witnesses. Darrow incorrectly believed that it was Sullivan who had notified the DA of the bribery scheme. One of Darrow’s old friends, W.W. Catlin, visited Darrow before he was charged and wrote:

I am assuming Darrow is guilty because his course, not only here but elsewhere, and his talk, justifies the belief that he thinks such a course was right, under the conditions existing. . . . Darrow said no word to me of his innocence, or regret that anyone had resorted to bribery. His whole talk was divided between intense and bitter attacks upon Larry [Sullivan], and a shuddering fear of [prison].

Darrow was guilty. There is no doubt about this. Darrow’s investigator who had organized the bribe, Bert Franklin, cut a deal with the DA to testify against Darrow in exchange for immunity. Darrow’s longtime lead investigator, John Harrington, who Darrow had brought from Chicago to help bribe witnesses, also agreed to testify against Darrow. Finally, prosecutors were able to trace the bribe money back to the $10,000 check Darrow had given to Olaf Tvietmoe in San Francisco on September 1, 1911.

There aren’t many lawyers who could or even would defend a client like Darrow in a case like this. Darrow’s sudden reversal had made him widely hated in far-left circles. One of the only men up to the task of defending Darrow was Earl Rogers. Like Darrow, Rogers had a larger-than-life persona and was known for his flamboyant courtroom antics. He turned trials into circuses in order to have his clients acquitted. Also like Darrow, Rogers was accused of using less than legal means to prevent witnesses from testifying against his clients. Very much unlike Darrow, however, Rogers’s motivations were purely mercenary.

Rogers would represent anyone, no matter how guilty or unsavory they were, as long as their checks cleared. Rogers’s brilliant deductive mind and flair for courtroom dramatics made him the basis of the popular film and television character Perry Mason. Rogers was also a high-functioning alcoholic, and his pre-court benders became legendary. Rogers visibly worsening health from his alcohol abuse created many headaches for Darrow during the trial.

Before I describe the bribery trials of Darrow, there are two facts that should be mentioned to frame the drama that unfolded. The first is that Darrow was definitely guilty. Of course, the evidence against Darrow was always overwhelming. However, during the trials, Darrow and Rogers would aggressively call much of that evidence into question.

Adela Rogers St. Johns, Earl Rogers’s daughter, stated in her biography of her father: “I never had any doubts [of Darrow’s guilt], not even before one of my father’s private conversations with Darrow included an admission of his guilt to his lawyer.” Rogers St. Johns had little reason to lie about Darrow’s confession of guilty, though she did come to hate Darrow for his hypocrisy and corruption.

The second fact that further confirms Darrow’s guilt was found in a letter from Darrow to his son that was unearthed in 2011. The letter establishes that in 1927, more than 15 years after the bribery trials, Darrow directed his son to pay Fred Golding, one of the jurors in his first trial, $4,500. That sum was the equivalent of $80,000 today.

Golding played a leading role in Darrow’s first bribery trial, and although the letter didn’t include an explanation, it virtually confirms that some kind of illicit relationship existed between the two. There is nothing to explain the payment otherwise. Although I have nothing to base this on, I suspect that Darrow bribed or otherwise influenced Golding during the first trial, and then Golding shook down Darrow for more hush money after Darrow had repaired his reputation and began earning huge legal fees again.

Darrow’s first bribery trial was a clown show. Crowds of Darrow’s supporters attended each day and had exaggerated reactions to any move by the defense team: Jokes from the defense or embarrassing missteps by the prosecution were greeted with roars of laughter from the crowd, Darrow’s moralizing sermons prompted the crowd to break into tears. Earl Rogers skillfully antagonized the prosecutors, mocking their appearance and mannerisms. The presiding judge was inexperienced with high-profile felony cases and could not control his courtroom. At one point, a prosecutor almost physically attacked a member of the defense team over an insult.

The trial was never about the evidence; the evidence only went one way: Darrow had been caught red-handed in front of several reliable witnesses. The only real argument that Rogers could come up with to challenge all the damning testimony against Darrow was that Darrow was smart, and it would be very stupid for a lawyer in Darrow’s position to show up to the scene of an illegal bribe money handoff. Darrow fumed at Rogers’s argument and Rogers could barely contain his disdain for Darrow, who he had once considered a hero but came to see as a monstrous hypocrite.

The strangest incident during the trial came after a prosecutor requested that the court’s bailiff, who was responsible for caring for the jury (which was sequestered in a hotel for the duration of the trial), be removed for showing favoritism to the defense. The bailiff was Mexican, and obviously very friendly with a Mexican attorney on the defense team. The two men would regularly converse with each other in Spanish and were rumored to be related to each other.

Shortly afterwards, Fred Golding, the juror who Darrow would make a large payment to more than a decade later, reported to the judge that he had seen an intruder trying to break into the jurors’ hotel rooms. The bailiff echoed this claim. Without any evidence, Golding began to insist that the intruder must have been an agent of the pro-business prosecution trying to interfere with the jury. I suspect that this incident was entirely fabricated in an effort to prejudice the jury against the prosecution.

The bailiff resigned, claiming he wanted to avoid the appearance of bias, but his resignation was announced in a way that made it seem like the prosecution was merely acting out of racism.

Afterwards, the jury turned decisively against the prosecutors. The facts of the case did not matter. The evidence did not matter. The jury barely deliberated at all before voting to acquit Darrow of jury tampering.

Los Angeles prosecutors and even reporters were flabbergasted. Darrow had been caught red-handed attempting to bribe Lockwood in broad daylight. The evidence against him was overwhelming. The alternate theory that the defense had presented in court, that Darrow was actually the victim of a complex frame-up sponsored by big business that involved many of his long-time associates and former trusted friends, did not make sense at all and had no evidence to support it. Darrow’s acquittal was a purely political verdict from a deeply compromised jury.

Darrow did not have long to celebrate. Prosecutors decided to pursue Darrow for his successful bribery of Robert Bain, the elderly Civil War veteran, who had come forward after Darrow was first charged. Although the case against Darrow was superficially weaker for this bribery, relying mainly on testimony from Darrow’s co-conspirators who had flipped, Darrow lost an important advantage before trial began.

Rogers had become fed up with Darrow’s arrogant behavior and began to have reasonable doubts about Darrow’s ability to pay his legal bills. Although Darrow still had a loyal circle of sycophants willing to attend the trial, his wealthy backers in organized labor felt betrayed by his handling of the McNamara case and abandoned him. Since Rogers was always just in it for the money, he refused to defend Darrow a second time. He checked himself into a sanitorium, nominally to receive treatment for alcoholism, and washed his hands of the case.

Darrow’s strategy for the second bribery trial was similar, but with one key difference: Although during the first trial there was at least the pretense that Darrow had been framed in a big business conspiracy, during the second trial Darrow tried to argue that the bribe wasn’t really a crime in a moral sense. In fact, at many points during the trial Darrow tried to justify the bombing of the L.A. Times building.

Darrow said Jim McNamara blew up the building and killed all those people because:

[H]e had seen those men who were building these skyscrapers, going up five, seven, eight, ten stories in the air, catching red hot bolts, walking narrow beams, handling heavy loads, growing dizzy and dropping to the earth, and their comrades pick up a bundle of rags and flesh and bones and blood and take it home to a mother or a wife… He had seen their flesh and blood ground into money for the rich. He had seen the little children working in factories and the mills; he had seen death in every form coming from the oppression of the strong and the powerful; and he struck out blindly in the dark to do what he thought would help....I shall always be thankful that I had the courage [to represent him].11

These are not the words of someone who felt sorry about what he did or who cared deeply about justice, social or otherwise. Rather, Darrow was a cynical activist putting on performance art in an effort to save his own skin.

The second jury was so unnerved by Darrow’s attempts to justify the bombing and convinced by the testimony against Darrow that they voted to convict 8-to-4 at the end of trial. For reasons unknown, four jurors refused to vote to convict Darrow under any circumstances. It’s possible that Darrow bribed members of the second jury, though there’s no evidence of this. Since in criminal cases juries needed to vote unanimously in order to reach a verdict, the judge declared a mistrial over the “hung jury.”

Faced with two failures to convict Darrow on overwhelming evidence for crimes he was clearly guilty of, L.A. prosecutors had reached an impasse. Although they had the opportunity to refile charges against Darrow for the Bain bribery, the lead prosecutor didn’t want to risk another political acquittal. He privately reached out to Darrow and told him that prosecutors would not refile charges if Darrow left the city immediately and agreed to never practice law in California again. Darrow took the deal.

After the trial, Darrow was completely disgraced in leftwing circles. Labor leaders believed that they had been cheated by Darrow’s repeated false claims of the McNamaras’ innocence and apparent theft of the defense funds. Far-left activists (including eventually the McNamaras themselves) felt that Darrow had rushed the McNamara case to a premature guilty plea in an effort to save himself from bribery charges. However, despite this disgrace, slowly his reputation repaired itself.

Because Darrow had been acquitted once, he claimed that the bribery allegations were never substantiated. He just ignored the second trial where jurors refused to acquit. He insisted that he was innocent until his dying breath.

Over time most people forgot the scandalous details of Darrow’s bribery trials. This was before the internet allowed people to quickly investigate claims. Pretty much everyone who wrote about the trial at the time thought that Darrow was guilty, and obviously guilty at that. Afterwards, the consensus emerged that he was innocent, if the bribery trials were remembered at all. Despite claiming that he had “retired” after the second bribery trial, Darrow soon resumed his legal work.

Organized labor never forgave Darrow for his betrayal and he was considered persona non grata by the labor movement for the rest of his life. However, Darrow found a new niche for his talents by volunteering his legal services in high profile race-related cases, often defending minorities against alleged racist frame-ups. Although I haven’t looked into these cases, I think there’s good reason to be skeptical of the people Darrow defended.

Darrow briefly made headlines representing Leopold and Loeb, two millionaire teenaged prodigies who murdered a child to see if they could get away with it. The public was outraged when it learned that Darrow had accepted a $70,000 fee (the equivalent of $1.2 million today) to defend the pair, and even more outraged when he helped them escape the death penalty with a novel but somewhat dubious insanity defense.

The biggest rehabilitation of Darrow’s career came from the Scopes Monkey Trial. Although the “trial” occurred in a courtroom, it was really a publicity stunt to generate attention for the city of Dayton, Tennessee. The entire affair was heavily scripted from the outset. After the State of Tennessee passed a ban on the teaching of evolution (with small fines for teachers who disobeyed) the American Civil Liberties Union, which Darrow had helped to found, offered to finance the defense of anyone who was charged with violating the ban.

Dayton businessmen and politicians met with John Scopes, a local schoolteacher who wasn’t sure if he had ever actually covered evolution in his classroom, but coached his students to claim that he did. Scopes would be “charged” with a crime in order to generate attention for the town, drumming up business for local hotels and restaurants. Former presidential candidate and outspoken religious fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan offered his services as prosecutor. Darrow was hired to lead the defense.

The Scopes trial was a national sensation. The plan to attract business to Dayton worked and soon the town was flooded with thousands of journalists and spectators. It was the first trial to be broadcast on radio nationwide, and was less of a legal preceding than a piece of performance art between the two eccentric lead attorneys. Scopes was convicted but the decision was later reversed by a higher court on a technicality. The law would remain on the books in Tennessee until 1967, though it went unenforced.

Although the media event came and went, eventually the story was made into Broadway play and then a movie, Inherit the Wind (1960). In the movie, the trial was presented as a real criminal case rather than a staged publicity stunt. The real-life story was replaced with a moral parable about the dangers of religious fundamentalism and McCarthyism. As the hero of the movie, Darrow was catapulted once again to national fame as a humble crusader for justice and civil liberties.

Although Darrow was a crusader for many things, justice wasn’t one of them. His actions in the L.A. Times Bombing case reveal that he defended murderers because he supported murder, and he was happy to represent terrorist bombers because he thought terrorist bombings were good. This was not theoretical for him. He was not just giving his clients the benefit of the doubt or ensuring that they received a fair trial. He broke the law in order to prevent trials from being fair.

It is remarkable that Clarence Darrow, who was openly corrupt and effectively premised his career on helping the guilty to walk free (in exchange for huge fees), has maintained a reputation as a brilliant and innovative lawyer. His arguments were not convincing or truthful. He would wink at jurors (at least the ones who he didn’t bribe) and then suggest that the victims deserved to be killed for political reasons. It was not complicated. The law did not enter into the equation, and neither did justice. People like Darrow should not be lawyers. They should not be allowed into a courtroom. No one should indulge these performances, which still continue today.

I come from a family of lawyers, they are trained sophists. If you have an understanding of logical fallacies you can run circles around them, they proceed to get angry and attempt to tone police you. They almost always have no sound arguments for what they say.

I enjoy these articles where you give your pov on leftist figures, related to the Bonus Army (which you've covered here) have you looked into Smedley Butler? I suspect his entire Wikipedia page is propaganda.

Given the 10th anniversary of Trump coming down the golden escalator and announcing his campaign, I recently re-read The Flight 93 Election by Publius Decius Mus (Michael Anton writing under a pseudonym because at the time a mainstream conservative intellectual was not allowed to like Trump), and I'm impressed with how good his political judgement is. He also has an online American foreign policy course through Hillsdale College (about 4-5 hours of lectures) that is really great.

Something that attracted me to this substack and Anton's work is that you both articulate what the current stakes are and realistic paths to political victory. In a talk he mentioned that Claremont Review of Books rejected the essay, showing how unpopular it was to support Trump at the time. Anton was working a corporate job where publishing under his real name would get him fired, a situation probably familiar to most people reading this. I think a post on The Flight 93 Election and the climate surrounding it from your pov would be interesting. Fallout New Vegas review in Claremont Review of Books soon.