Communists killed a bunch of people at a Veteran's Day parade in 1919 and got away with it

The Centralia Massacre and cover-up

This article was originally published about 6 months ago. I’ve decided to make it free because more people should know about this story. Please become a paid subscriber right now to support my work. Paid subscribers also have access to all the podcast episodes on this Substack.

1919 is often described as a year of national hysteria. Government officials and ignorant Americans began to falsely claim that the country was on the verge of a communist revolution. They took out their unjustified fears of communism on immigrants, peaceful political dissidents, minority groups, and labor organizers.

A closer examination of 1919 reveals that these fears were not so unfounded. The period was marked by huge labor unrest, some of it sponsored by the communist-controlled International Workers of the World (IWW). More than 4 million workers, about 20% of the nation’s total workforce, would go on strike at some point during the year. Although the 1918 Seattle General Strike was put down without bloodshed, massive incidents of public violence followed the 1919 Boston Police Strike. That crisis was only ended with military intervention, thousands of uniformed soldiers poured into Boston. Other large strikes paralyzed major cities.

Bloody racial conflicts broke out across the country. There were more than 36 large scale race riots. The death toll was supposedly in the hundreds. Although some scholars today have placed the blame for this racial turmoil almost exclusively on “white terrorism,” there is good reason to be skeptical of scholars.

There was an extended terrorist bombing campaign, primarily led by Italian Anarchists. Dozens of bombs were detonated in major cities and quiet suburban neighborhoods. These attacks would culminate in the 1920 Wall Street bombing, which killed 40 people outright and seriously injured more than 100 more. The perpetrators were never formally identified.

A huge crime wave accompanied this political and racial violence. The automobile enabled fast getaways and a wave of armed robberies. Further exacerbating problems was a huge tide of immigrants, more than 15 million between 1900 and 1915. These immigrants were often in desperate conditions. Many turned to crime. Building traditional criminal cases against members of close-knit immigrant communities proved extremely difficult for law enforcement. Suspects could quickly disappear into a new identity or just leave the country. Criminals caught red-handed could easily find other immigrants willing to lie or cover for them in court.

This was a scary period. These problems seemed new, they were all happening at once, and normal people had no idea what was going to happen next.

The Pacific Northwest was flashpoint of labor tension. It had a large population of transient laborers from the mining and logging industries. Many of these men were from overseas. Lacking moderating influences like local connections or families, these large groups of young men were prone to radicalization and violence. Furthermore, the suppression of IWW organizing in Montana, Arizona, and Idaho led to a large number of radical laborers relocating to Seattle and surrounding areas in the hope that they’d be able to operate more freely in a large cosmopolitan city.

The outbreak of WWI caused a huge boom in industrial and logging activity in the Pacific Northwest. The IWW was opposed to all war (at least those started by capitalists, it was indifferent to communist aggression) and IWW members were often very active in the anti-war and anti-draft movements. What followed was a wave of sabotage and work disruptions suspected to have been caused by IWW members. The founder of one logging company stated1 at a congressional hearing on the topic:

As soon as war started, the I. W. W. became very active in the woods. I do not know whether there was any connection between that organization and German agents. We met their opposition, which was manifested by driving spikes in logs, blowing up logging engines, starting fires in the woods, and anything else that would delay production.

Our company had one very bad fire that the I. W. W. set. We had an engine blown up and a man killed, though I cannot be sure that the I. W. W. did this. We found an average of one spike a week in the logs at the mill, whereas usually we found one in six months or one a year. One ship that sailed from Bellingham with lumber was reported on fire at sea from the result of a fire bomb set aboard before she sailed.

Not more than 20 percent of the men employed were engaged in such activities; the other 80 percent were loyal and earnest. When the loyal legion was formed, nearly all the loggers and millmen in the Northwest, including Oregon, Washington, and part of Idaho, joined. From that time on we had no trouble.

The “loyal legion” he was referring to was the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, a patriotic union organized by the US military to allow anti-IWW workers to organize. In 1917 an IWW-led strike seriously disrupted timber production, threatening the war effort. The military intervened directly, addressing many of workers’ more reasonable concerns in concert with management. After the war, the Loyal Legion’s role as the primary social organ to oppose the IWW was taken over by the (then brand-new) American Legion. Although nominally an apolitical veteran’s organization, in practice the American Legion acted as a counterbalance to the increasingly disruptive public influence of radicalism in all forms. IWW members and Legionnaires regularly clashed across the Pacific Northwest.

Conflicts between IWW members and locals became increasingly bloody. In 1916, the small town of Everett, Washington had a major problem with IWW organizing. The IWW organizers, there to support a 5-month strike at a local shingle factory, would hold meetings in city streets, shutting out all traffic and effectively taking over any area they rallied in. It was deliberately confrontational. Local police didn’t have the manpower to respond to these flashmobs. After the city banned this behavior, the IWW refused to back down. Eventually, the locals forcibly ejected IWW members. Several IWW members were tarred and feathered, the rest were beaten with axe handles and run out of town.

IWW members in Seattle were incensed by this removal. They chartered two boats, loaded them up with 300 IWW members, many of whom were armed, and sent them back to Everett. When the first boat arrived, it was met by 200 locals led by the town sheriff. When the Sherriff told them they could not land at the town, one of the IWW members replied “The Hell we can’t!” and a single shot rang out. A huge gun battle ensued, lasting for 10 minutes. IWW members crowded on the deck were forced into the water, where several drowned. The boat almost capsized and the pilot house was riddled with bullets. Both sides, tightly packed together, suffered casualties.

The boats retreated to Seattle and all of the survivors were promptly arrested. However, both sides claimed the other had shot first. With so much contradictory testimony and no hard evidence either way, a jury refused to convict the IWW members and all the charges were later dropped. Despite the ambiguous legal outcome, communist disruptions in Everett ended shortly afterwards.

Early in 1919, communists attempted a General Strike of 65,000 workers in Seattle, the first of its size and scope in American history. Many claimed that it was the planned start of a communist revolution. Thanks to the quick-thinking of the town’s mayor, Ole Hanson, the strike was ended without any bloodshed. However, tensions remained.

Centralia, Washington was another town plagued by IWW organizing. Fights regularly broke out between IWW members and members of the American Legion. Exacerbating the situation was that some American Legion members from the area had been part of the limited American intervention during the Russian Civil War. Having witnessed Bolshevism firsthand, they saw the IWW’s presence as a barely-disguised attempt to implement a similar regime in America.

One of these American Legion members was Warren Grimm. Grimm was a high school football star who became a prominent attorney in Centralia. During World War I, he was deployed as an officer with the American Expeditionary Force to Siberia. Upon returning from Russia, he publicly spoke about the threat of Bolshevism to the United States.

In 1918, members of the local Elk Lodge, a patriotic fraternity backed by local businesses, broke away from a Red Cross parade through Centralia and suddenly stormed into the local IWW meeting hall. The IWW members were beaten and run out of town. The meeting hall was trashed, the literature destroyed, and all their furniture was tossed into the street and sold, nominally to benefit the Red Cross. No arrests were made and the Elk members weren’t punished.

Gradually the IWW returned to town. They rented a new meeting hall. The tensions slowly flared up again. A partially-blind communist newspaper vendor was forced into a car, driven out of town, and told to stay out for good. The communists lost most fights that they had with the locals. When the communists heard another parade was planned on Armistice Day (today known as Veteran’s Day), they assumed it would be followed by another raid on their headquarters. These fears were bolstered when the local police said that they could not provide special protection to the meeting hall: their men would be scattered all over town directing the parade and couldn’t be moved just on account of a rumor.

The communists consulted local lawyer Elmer Smith, who was friendly to the far left. Smith said that it would be legal for them to defend themselves if their meeting hall was attacked. The communists took his words to heart and hatched a plan that went far beyond his intent.

The communists stockpiled weapons and placed gunmen on the second floors of nearby buildings. They also had a three man sniper team placed on a nearby hill overlooking the intersection. Essentially, they created a massive killzone in front of their headquarters. If the rumored vigilante raid came during the parade, they would massacre the perpetrators.

This approach stretches the legal definition of self-defense until it breaks. They weren’t planning to take out people who had broken into their headquarters and attacked them, they were planning to fire into a large crowd of unarmed people at a parade for veterans. They had snipers hundreds of meters away: this was not planning for mere defense of self and property. There was no way for them to discriminate between targets. When coupled with the fact that they were all members of an organization backed by a foreign government trying to achieve radical political change in the US, and the people they had designated sharpshooters were anonymous transient workers (some of the shooters are still unidentified to this day), this plan went well beyond what any reasonable person would consider appropriate to defend themselves.

The day of the parade passed mostly uneventfully. The American Legion contingent from nearby Chehalis, Washington marched by the IWW meeting hall without incident. However, when the Centralia contingent of the American Legion, led by Warren Grimm, paused at the corner before passing the hall, shots rang out.

Although it’s much debated what prompted the shots, it’s generally agreed that the first victim was Grimm. He was hit with a high-powered rifle bullet fired from the second story of a nearby hotel and died a few minutes later. When he was shot he was standing still in the middle of the street, having just ordered the men in his unit to tighten up their formation. Bullets soon began to rain down on the veterans from several different directions. Another man, Arthur McElfresh, was shot in the head with a rifle bullet that likely came from the sharpshooters on the hill.

The Legionnaires realized what was going on and stormed the building where most of the shots were coming from, the meeting hall, en masse. They were entirely unarmed. The unarmed veterans quickly overpowered most of the communists hiding inside. Many had already fled. One of the communists, a lumberjack named Wesley Everest (himself a veteran), shot and killed Legionnaire Ben Cassagranda with a pistol in front of several witnesses.

Everest bolted out the back of the hotel into the nearby woods, pursued by several unarmed Legionnaires. One of the Legionnaires, Alva Coleman, was given a nonfunctioning revolver by residents of one of the houses he passed during the pursuit. When Coleman was shot by Everest, who would periodically turn to fire at the group pursuing them, he passed the nonfunctioning revolver to Legionnaire Dale Hubbard. Hubbard was known in town for his exception athletic ability and eventually pulled ahead of the rest of the pursuit group. He caught up to Everest alone as Everest was preparing to ford the Skookumchuck River.

Hubbard pointed his useless gun at Everest and told Everest to surrender. Everest turned and shot him, then walked over him and emptied his pistol into Hubbard’s body. The rest of the pursuers quickly caught up to Everest, now out of ammunition, and brutally beat him before dragging him back to town.

Groups of veterans and vigilantes roamed the town and surrounding countryside, arresting any known communist they could get their hands on. The lawyer the communists had consulted, Elmer Smith, was arrested as well. Several days later Deputy Sheriff John M. Haney was accidentally shot and killed by a posse after he failed to give the proper countersign when approaching a group searching for suspects at night.

On the night following the massacre, the power was shut off in town and a large mob formed outside the jail where the communists were being held. Everest, the only man who had actually been witnessed directly shooting one of the Legionnaires, was dragged out of his cell and hanged with telephone wire on the edge of town. His body was shot several times. Local coroners, angry about the massacre, refused to handle Everest’s body when it was recovered the next day so it was stored in an empty jail cell in full view of the captured communists.

The trial began several months later. The prosecution’s case was straight-forward: most witnesses testified that the parade had stopped before it passed the meeting hall. A few scattered shots suddenly rang out, killing Grimm at the head of the column, there was a brief pause, then a huge torrent of gunfire erupted from the meeting hall and surrounding firing positions simultaneously. The Legionnaires didn’t begin rushing the meeting hall until after the firing had already started. This was backed up by the evidence. Grimm and the other man killed on the street had been shot with rifles, rather than the pistols that the communists in the meeting hall were found with.

The defense’s case was yet another example of a familiar pattern that you see over and over again from communists during the period. One story after another was presented, only to be discarded after it was proven to be a lie. At first, the defense boldly claimed that the American Legion was in fact not responsible for the shooting at all. Rather, unknown to the Legionnaires, a group of local businessmen and members of the Elk Lodge who had raided the meeting hall in 1918 had hatched a scheme to use the parade as camouflage for another raid. When the vigilantes stormed the hall, the communists fired in self defense, tragically catching the Legionnaires in the crossfire. The defense claimed there were no shooters outside of the hall.

This story was absurd and ignored all of the physical evidence (shell casings, windows broken by gunfire), along with reliable testimony from the parade attendees, who all described roughly the same scene. It even contradicted two signed confessions from one of the communist sharpshooters on the hill, who claimed that they had planned in advance to fire from multiple positions on any raid and that he began firing on the parade after he heard gunshots. The communist who signed those confessions later tried to retract them, claimed they were made under duress, and entered a plea of not guilty on the grounds of mentally insanity. Another communist who was inside the meeting hall but unarmed testified that the Legionnaires did not rush the building until after the shooting had already started. He said that it was one of the communists on the second floor across the street who fired the first shots.

The judge refused to admit testimony on any alleged plot of local business owners and their goons from the defense unless it could be shown that Grimm, the first victim, was part of the plot. Afterwards, the defense’s story changed radically. They claimed that not only was Grimm part of the conspiracy, he was one of the leaders of it. Rather than having been shot in the middle of the street by accident, as the defense had claimed in its opening statement, Grimm was actually shot at the doorway of the meeting hall as he was leading a charge of Legionnaires to attack the innocent communists.

The story was absurd. It was contradicted by many of the defense’s own witnesses earlier in the trial. Two of the later witnesses called by the defense were so obviously lying that they were arrested for perjury upon leaving the courtroom. Many “impartial” witnesses called by the defense were revealed during cross-examination to have suspicious motivations. One local high schooler who testified for the defense tried to conceal the fact that both of his parents were labor organizers. A morbidly obese woman who testified that Grimm was shot just outside the meeting hall ended up having lived in the same boarding house as Wesley Everest, the communist shooter who had been lynched. She had gone by several fake names beforehand for unclear reasons.

Having already changed its story once, the defense again shifted the narrative. They stopped claiming that the only firing had come from the meeting hall and admitted that there were several groups of communist gunmen surrounding the killzone. Rather than Grimm leading the raid, blame was placed on a local doctor who had claimed at an coroner’s inquest on the night of the shooting that he had suggested a raid on the meeting hall earlier in the day and the carried it out when the shooting began. At trial, the doctor was revealed to be deaf. What he thought was people acting on his earlier suggestion was actually men scattering due to the rifle fire they received.

Perhaps the worst day for the defense came when they called a radical priest from Seattle, employed by the defense as an investigator, to testify that Grimm was shot at the door of the entrance hall. After he testified to that effect for the defense, the prosecution produced an (apparently stolen) letter written by the priest to the defense lawyer in which the priest said that Grimm was not involved with the raid. The letter was genuine and totally discredited the witness, though it’s not clear how prosecutors obtained it. It’s been suggested that the US Secret Service was involved in the theft.

The defense made more and more dubious accusations. One of the witnesses they called claimed that the first shot had in fact been fired by one of the Legionnaires in the crowd, even though this wasn’t mentioned until the end of the trial and none of the other defense witnesses said anything to that effect. The uncle of Dale Hubbard, the Legionnaire who was killed pursuing Everest, was a local business owner. The defense claimed that he was involved in the planned raid and had personally directed it in Centralia that day, but hotel records proved that Hubbard’s uncle was actually in Portland at the time. The defense was throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick. Nothing the defense said was true.

The jury deliberated for a short time before convicting seven of the communists of second-degree murder. Two of the defendants, including the lawyer Elmer Smith, were acquitted. The communist who had signed the two damning confessions was found not guilty due to mental insanity.

The verdict made almost no one happy. Although little doubt remained that the men convicted were guilty of firing into the crowd from multiple positions, if prosecution’s story was accepted, which it appeared to have been with a conviction, then the men would have been guilty of first degree murder and eligible for the death penalty. Communists maintained, despite the overwhelming evidence against the men, that they were innocent and were being persecuted for self defense. The judge, apparently unimpressed with the defense’s arguments, imposed the maximum sentence of 25-40 years in prison on the men convicted of murder.

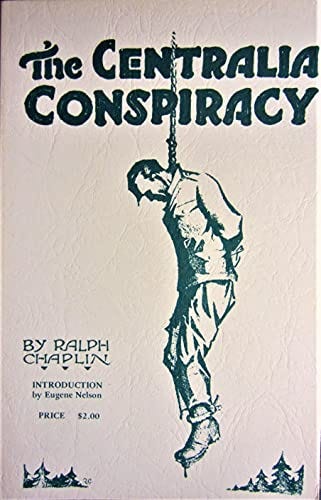

Sadly, they got away with it in the end. Over time a “wrongfully accused” narrative similar to the one that had been built around Sacco and Vanzetti developed around the Centralia massacre perpetrators. In 1920 a bestselling book was published called the “Centralia Conspiracy” that rehashed the initial argument of a business plot to attack meeting hall that the defense had attempted during the trial. New witnesses came forward, but were never subjected to cross examination. Testimony that had been revealed to be false during the trial was accepted at face value.

Soon after, the acquitted lawyer Elmer Smith began an effort to have the convicted men exonerated. Although the Washington Supreme Court upheld the convictions and Smith was disbarred for unethical behavior, subsequent governors, looking to capitalize on the growing leftist populist frenzy of the New Deal era, pardoned or paroled all the convicted murderers throughout the 1930s.

There’s one anecdote that I think sums up efforts to free the men. After being released from jail one of the shooters, Eugene Barnett, gave a recorded interview in 1940 on his experiences. At trial, the prosecution had argued that Barnett was the man who had shot Grimm, starting the massacre. Several witnesses spotted Barnett carrying the murder weapon. At the time of the interview, Barnett was married to a Canadian IWW member who was working for an American government New Deal cultural agency. Barnett said:

So when [the Legionnaires] broke through in [the meeting hall], they found that the boys had ran out the back of the hall. Wesley Everest, the man who had been shooting from inside the hall, was a returned soldier himself. He was wearing his uniform that day and he was shooting with the gun that he had brought back from France. He'd been cited for bravery over there and had been denied his medal because they'd found that he was a radical. He told the boys that day, he said, ‘I fought for democracy in France and I am going to fight for it here.’ He said, ‘The first man that comes in this hall, why, he's going to get it.’ So he made his stand right in the middle of the floor that day.

There was one problem with Barnett’s story: Wesley Everest, though he was a veteran, never fought in France. In fact, he hadn’t even been deployed overseas. After being drafted into WWI he was recognized as politically unreliable and assigned to a spruce cutting division in the Pacific Northwest. Everything these people said about him was a lie. It wasn’t until 1986 that a historian actually bothered to look up Everest’s Army record to confirm that this key part of the narrative was entirely fabricated. Barnett was still lying about basic details of the incident even after being freed from jail.

In the 1930s, communists began claiming that after Everest was lynched, the mob had castrated him, too. This was not mentioned by anyone until the 1930s. It wasn’t brought up at the trial. None of the prisoners mentioned it, though they had full view of the body from their cell. The eventual autopsy made no note of it. The castration was just another fake detail that communists decided to add in to enhance their narrative.

The story of the Centralia Massacre is sad, but it’s also instructive. Liberals did something indefensible, then they all came together to shamelessly lie about it for years. After about a decade, they managed to create enough dishonesty and confusion to have the murderers released from jail. Today, if you read contemporary articles on the subject, key details like the confessions or changing and repeatedly discredited defense narratives are totally missing. The general consensus is that it was a mutual “shootout” and that the veterans were the aggressors, even though that narrative was disproven at trial when the evidence and witnesses could actually be scrutinized.

On November 11, 1924, the American Legion erected a 10-foot-tall bronze statue, dubbed The Sentinel, to honor the men killed during the Centralia Massacre. Today, that statue is directly faced by a grotesque mural commissioned in 1997 to honor Wesley Everest, one of the murderers. The mural is a good reminder of what happens when conservatives fail to keep the fire of their history burning.

If you enjoyed this article. Please become a paid subscriber to support my work. Every subscriber makes a big difference for me.

Americanism versus Bolshevism, 56

“umm, ackchyually, the communist only emptied six rounds into the unarmed man lying on the ground, not seven. Pretty problematic. Do better, Chud.”

Amazing how much of these stories have been completely memory-holed.