Interesting chapter details "Why Denikin failed"

More from "With Denikin's Armies"

As I’m sure readers of this Substack have detected, the Russian Revolution and Civil War are extremely interesting to me. One of the most interesting aspects of these events is just how up in the air the outcome was, even up into the final stages of the war. Read my Introduction to the Russian Revolution: The Bolsheviks were constantly on the verge of defeat.

The White Army (a term for the politically schizophrenic loose alliance of anti-Bolshevik military forces) fell into miraculous victory after miraculous victory. For the first two years of the war, virtually no one thought that the Bolshevik dictatorship, incompetent in both military and civil administration and extremely unpopular in every area it took control of, would last for more than a few months. The Whites only needed to finish off their critically-wounded enemy.

And yet, the killing blow never arrived. Although White victory seemed assured, they ended up losing and losing very badly at that. The Whites fell apart and turned on each other with every new twist of fate while their enemy remained organized and determined in the face of every catastrophe. The Bolshevik victory, rather than being an inevitable process of history, was a preventable disaster. It was still very nearly prevented in spite of all the mistakes that the Whites made.

Most striking to me about this situation is how everyone, even the Whites, seemed to be aware of it. You just could not convince people to avert their fates. The Bolsheviks weren’t impossible to beat, people often didn’t even bother to fight them. The problems facing the Whites weren’t impossible to solve, they just didn’t bother to solve them. There wouldn’t even be an attempt to address obvious issues until it was far too late for remediation to make any difference. When these half-hearted efforts failed, this only confirmed in the eyes of many that defeat was “inevitable.” The Whites’ disorganization prevented them from taking advantage of opportunities as they emerged and made every defeat all the more damaging. There was a generalized passivity and resignation that led to so much suffering in the years that followed.

It often seemed like the Whites didn’t want to win. They wanted to speak their minds. They wanted to win factional feuds or get revenge on individuals or populations that had aggrieved them. They wanted personal glory or satisfaction at the expense of any kind of larger plan or system. They wanted to make money. Their victory was assured, right? They were so good and their enemies were so bad. How could they lose? These people seemed to be willing to do anything but what was required to actually win. There were many moments where just one person showing a bit of nerve, or at least not behaving badly, could have changed the outcome of the war. People could not get over themselves to save their own lives, or the lives of their loved ones, much less save their country.

I notice all of these trends in America today. Although our situation is very different than the one that the Whites found themselves faced with during the Russian Civil War, many of these problems and their solutions are eternal. If we are to lose, I think it will be because conservatives failed to take steps that were obvious all along. The good news about this is that the problems really are obvious. What’s lacking is a will to address these issues.

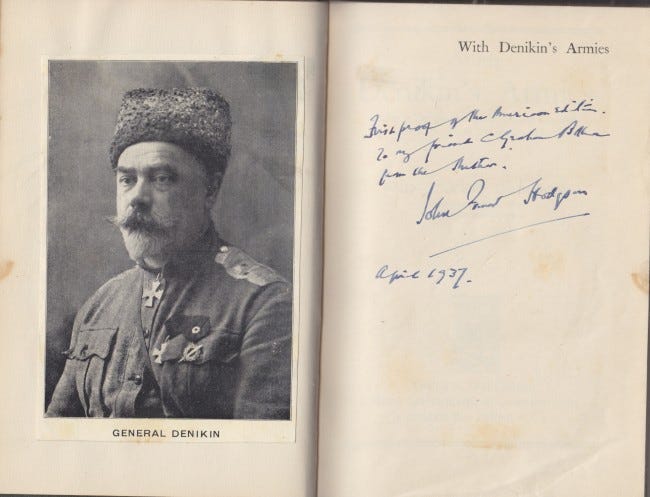

This brings us to With Denikin's Armies: Being a Description of the Cossack Counter-revolution in South Russia, 1918-1920 by John Ernst Hodgson. Hodgson was a British journalist who was tasked by a “group of newspapers” (I strongly suspect he was actually working for British intelligence as an observer) to act as a press correspondent in South Russia in 1919. I’ve already digitized one section of Hodgson’s book, detailing his (often entertaining) thoughts on the controversy surrounding Jews during the Russian Civil War. Hodgson concludes his memoir with a summary of why he thinks the Whites lost. I’ve reproduced that chapter below.

My hope is that if people today recognize the issues that people faced back then, it will help them when are confronted with those same problems in the present. As I said earlier, oftentimes the outcome of the struggle seemed to hinge on just one guy doing the right thing at the right time. You could be that one guy.

Times are good now, but there are things so bad we can’t even imagine them yet on the horizon. Navigating this situation is going to require unity of force and purpose among American conservatives, something that the Bolsheviks manifested in spades but the Whites never could quite seem to find.

One final note, I’ve added in bolding (not in the original text) to highlight sections that I thought were particularly interesting or relevant to our situation today.

And now to the excerpt:

[Begin selection pg 179]

CHAPTER XI

Why Denikin Failed

On December 23rd 1919 General Denikin told me that he attributed his defeat to the facts that the retreat of Koltchak and the elimination of Yudenitch had enabled the Reds to concentrate practically the whole of their forces against him. He appeared to pooh-pooh my suggestion that either the Bolshevik organization had improved or it had established some sort of prestige for itself among the peoples of North and Middle Russia. He was not even prepared to admit that the Soviet Government had for some time been trimming its policy to public opinion and had gradually taken on a more benign complexion. He must have known, however, that other, and graver causes, which existed within his own lines, had robbed him of what had looked at one time like certain victory.

The Russian character is a puzzling mixture of the frivolous, the deeply serious and the mystic. The upper classes, and those few of the common people who had had opportunities of acquiring real culture, were educated in a way beyond anything that had been attained in England. On the other hand the lower classes were steeped in abysmal ignorance, and displayed all the traits of creatures who had been for centuries the victims of neglect and oppression. The governance of Russia has always been in the hands of a haughty few, and the consequence is that no body of men has ever existed in the country with experience of administration or which has been entrusted with high civic responsibility. The deposition of Tsardom brought into being at once all the elements of faction which afterwards resulted in chaos. Monarchists, individualists, extremists, moderates and opportunists, none of whom had been tutored in statesmanship, pitched themselves into the battle for power; and the net result of it all, apart from the palpable facts of revolution, was to let loose dormant passions and vices, and to nurture those children of irresponsibility—bribery and corruption.

About the middle of 1919 the British sent out a complete 200-bed equipment for a hospital at Ekaterinodar. Not a single bed ever reached its destination. Beds, blankets, sheets, mattresses and pillows disappeared as if by magic. They found their way to the houses of staff officers and members of the Kuban Government. At this very time typhus and enteric were raging, and in a hospital of only 150 beds at Ekaterinodar the men were dying at the rate of twelve a day. They lay on bare boards, were covered with dirty sacks to which clung the detritus of their original vegetable contents, and were swarming with lice and fleas.

In 1919 we sent Denikin 1500 complete nurses' costume outfits. I did not, during the whole of my service with the Army in Russia, ever see a nurse in a British uniform; but I have seen girls, who were emphatically not nurses, walking the streets of Novo Rossisk wearing regulation British hospital skirts and stockings. Britain sent Denikin enough soldiers' clothing to equip an army twice the size of her own peace establishment. He never claimed to have had more than 300,000 men at his disposal; but neither at the Tsaritzin nor the Don front did I ever see as many as 25 per cent of the fighting men in British kit. This latter fact was explained in two ways, each equally distressing. The cognoscente said frankly that they knew the stuff was going astray, while the soldiers on each front told me that the Armies on other sectors were evidently being favoured by the British at their expense.

I saw and talked to young ladies of good social standing at Taganrog who were wearing costumes made of British officers' serge, and I can name Russian officers attached to the British Mission who deliberately "wangled" a double issue of clothing from our Ordnance and at once sold the surplus set at a fabulous price. The base towns were always full of well-clothed, lazy Russian officers while whole regiments at the front were wearing practically nothing but a print shirt and a patched pair of trousers. Almost every functionary in Russia holds some sort of rank and wears uniform. A magistrate at Novo Cherkassk, the Don Cossack capital, invited me to supper in November 1919. He appeared at table in a tunic of British khaki, with his badge of office sewn on to the collar. It is impossible to believe that we sent out clothing for the benefit of lawyers and petty civil officials.

It is possible to square almost anybody, high or low, in Russia—it always has been. Instead of recognizing this frankly, and coping with it by policeing and administering his towns, Denikin left the whole of the country over which his Army passed during his great summer advance to take care of itself. He cannot have been quite without good men to whom he could have entrusted the local government of South Russia, but that is the story put forward on his behalf. Members of his entourage told me that all the good and enlightened men in Russia had either been killed, or had deserted their country through fear or in disgust at Denikin's avowed democratic aims.

No matter how urgently trucks were needed to get British munitions to the front it was always possible for a local profiteer to bribe railway officials and obtain freight cars. This was done on a colossal scale. Peter Vrangel [Pyotr Wrangel] was the only man who dealt with this phase of corruption in a peremptory and thoroughly effective way [the author is almost certainly referring to Wrangel holding an emergency trial followed by an immediate public execution for a railway official who accepted bribes to transport merchants’ goods instead of civilian refugees during an evacuation].

While the battle was raging just north of Kursk ten British tanks were landed at Novo Rossisk. For weeks they lay on the jetty awaiting trucks on which they could be sent to the front. None came, but one night a typical Black Sea storm caused one of the tanks to slip its moorings, and the whole consignment slid quietly to the bottom of the harbour.

A functionary of any sort could always obtain a special engine for what he would describe as a special journey.

While the S.S. Warspite was unloading at Novo Rossisk a truck on the quay caught fire. The truck contained shells, and, by hitching an engine to it at once, it could have been hauled to a safe distance from the munition ship. Once the danger was realized there was neither an engine nor a man to be seen within hailing distance. A burning plank fell from the truck into the Warspite, and she was ablaze in a minute. She was quickly towed out into the harbour by the British sailors, and sunk, with all her freight of guns and shells, by H.M.S. Grafton, the old battleship which had been sent out to act as guardship in the Black sea.

A huge quantity of our small-arm ammunition and 60,000 shells were stacked for months at Berdyansk, on the Sea of Azov. The British mission, who considered the town to be vulnerable, warned the Russian staff repeatedly. Just as the battles were opening which should have given Denikin permanent possession of Kieff [Kiev] and Orel, Makhno the brigand sprang into activity near Ekaterinoslav, and within ten days he had blown the Berdyansk dump sky-high.

The staff were full of excuses for this calamity, the main one being a shortage of rolling stock; but about this time I saw a general's train coming back from the front. It consisted of forty-four trucks and coaches, and the gallant officer carried with him his own orchestra, his operatic stars and his troop of acrobats. Apart from the economic tragedy involved, it does not call for a political genius to gauge the effect of this spectacle on the minds of the starved and shivering peasants who watched the pageant from the wayside station platforms.

Whilst at the Tsaritzin front I wrote an article for my paper in the course of which I referred to both the corruption and the lack of efficiency which distinguished Denikin’s railway administration. I asked that the British Government should recognize this, and, if it really meant business, heavily to reinforce the railway section of our Mission at once, so that the goods we were sending the Russians could be seen through by us from the coast to the front. I asked Mr. Churchill “not to spoil the ship for the sake of a ha’porth of tar.” The head of the British Military Mission, who censored my article, struck this paragraph out before dispatching the cablegram. When I asked for an explanation he said there was no need to raise the cry because the matter was already having the attention of the War Office. No excuse can, therefore, be offered by the British Government if they were not prepared in a great degree for the impending catastrophe.

The measures which Denikin took to ensure among his officers that high sense of discipline which alone could have taken him to victory were pitiable and belated. No ban was placed upon the expression of the most amazing and conflicting views. When soldiers, especially irregulars, forgather in wartime, loose and irresponsible conversation is always indulged in; but the British in France realized this, and G.H.Q. issued stern disciplinary orders which had the effect of bringing home to our officers the grave political and military danger attached to lapses of discretion. Some of the Russian officers were avowedly pro-German, others enthusiastically Anglophile. Some were out-and-out Tsarists, while others were mild democrats. A few were even infected with the virus of Bolshevism, but were too proud or too "respectable" openly to go fighting for the new creed. Many openly despised the French who, after all, were helping their cause. I have spoken to many Russians who sighed for the return of the old regime and who laughed at me for speaking of the illiterate lower classes in Russia as being their equals before the Lord. These officers placed their unfortunate compatriots upon a level with the negroes of our Empire. Can we wonder that the ultimate result of centuries of such social divisions was the cataclysm of 1917?

The drinking of vodka among the Russians was always a menace to their cause, but it was only when the final crash was upon them that orders were issued prohibiting its manufacture and consumption. The effects of the prohibition of vodka by the Tsar must have been both curious and debatable, but the effects of shortage under Denikin were appalling. It is no good imposing total abstinence upon a community by decree unless complete and sufficiently strong arrangements have been made in advance both to enforce the decree and punish those who violate it. The Russians have always been a hard-drinking nation, and a large section of the populace will drink spirituous liquor without regard to either its strength or its origin. Crude methylated spirit and other substitutes were consumed in large quantities. A British naval officer told me that in August the officers of a ship in the Russian Black Sea Fleet invited a few Englishmen aboard for dinner. The ship was known to be "dry"; but quite a quantity of "vodka" was served during the evening. It afterwards transpired that the Russians, desirous of living up to their reputation for hospitality, had actually drained the anti-freezing spirit from their big reserve compass in order to make their party a success. During the battles which raged around Kharkoff [Karkov] in November several members of the Russian tank corps were selling radiator anti-freezing mixture (part of the equipment given them by Britain) to the Kharkoff Hotel Metropole at a fabulous price. Surely it was the duty of somebody to inform our War Office of the way in which our generosity was being abused.

Discipline was always of a perfunctory kind, and towards the end was becoming deplorable. All through the long and victorious summer the streets of Rostov and of the other big towns were full of soldiers on leave, and it was not until the Army was in full retreat that a rigorous "press-gang" law was instituted for the shirkers. The retreat itself afforded many instances of slackness and of low morale. Officers and men, whether they had leave or not, were bolting from Kharkoff by hundreds, and the railway officials reaped a huge harvest by charging them as much as 20,000 roubles for the privilege of entering a south-bound train.

It may be that Denikin was not fully aware of the whole state of affairs within South Russia. I always had the idea that he was carrying too much on his own shoulders, that the elements of inefficiency and corruption with which he was surrounded were gradually squeezing his great work into oblivion. He was a soldier first and all the time, and, although he appeared to be a sincere and honest man, he did not possess that wide political vision and insight which alone will enable a commander, especially one who by force of circumstances is temporarily acting as a national dictator, to achieve triumph. He was all along, however, aided and advised by a powerful British Military Mission, to the head of which the facts were well known, and which failed to bring about those drastic reforms which were urgently called for, not only in the conduct of the campaign but in the interests of British prestige.

The whole history, both of our intervention and of the organizations which we set out to help, was a series of tragic blunders and inefficiencies. Everybody who was in Russia during the counter-revolution knows in his heart that the cause of the anti-Bolshevists needed and deserved either support or advice. If the giving of sound advice and of moral help by Whitehall was the correct solution, then from the very start we failed. Our information came mostly from sources tainted with Tsarism and unduly prejudiced against Bolshevism, and we were never placed in a position properly to focus the Russian peculiarities of character. A study of the geographical factor dispelled any hope of success for armed intervention, which, if it had been attempted on an adequate scale would have swallowed dozens of divisions. Our only hope would have been to send twenty-four divisions, six drawn from each of the four great Allied Armies, through Germany to the Russian border before concluding the Peace, and, with their aid, to have declared Russia to be an Allied Protectorate for the time being. It might then have been possible to convene the Constituent Assembly, and to have given it a good send-off.

It is very much to be feared that the only effect of outside muddling was to foment and perpetuate fratricidal strife, to embitter all international relationship, to spend huge sums of badly needed money, to withhold from the world the vast and invaluable stocks of foodstuffs and other commodities in which Russia is rich, and to raise within our own lands the hopes of all who were partisans of revolution and anarchy.

[End selection pg 190]

***

And that’s it! I’m constantly struck by the parallels between the problems they faced back then and the problems we face today. I highly recommend you read the entire book. With Denikin's Armies: Being a Description of the Cossack Counter-revolution in South Russia, 1918-1920 has been out-of-print for almost 100 years. Although used copies are impossible to buy, you can still find the book at certain university libraries (check WorldCat) or on Libgen dot is.

I’m eager to read the article later once I get cleared yet again by my probation officer. One aspect of the Russian Civil War that seems to happen often with nationalist/traditionalists vs communists is the similarity between an athletic high school student and a dangerous loner student. The loner student might jump the athlete from behind, but then plead mercy at the last moment when the athlete subdues him. The athlete has a sense of honor that somehow prevents that one last blow that will crush the loner and teach him through force never to mess with him again. The Whites (except Franco in the Spanish Civil War) seem to have an issue with that finishing blow. They cannot completely annihilate the enemy or band together long enough to route them completely. The Whites are too independent and aristocratic of morals in their approach. Only the military discipline of a General Franco or a General Wrangel overcomes that last hesitancy.

Ok, finally got the battery for the new ankle bracelet and read the piece.

Incredible. You mark the most pertinent parts in bold very well. The early bit about how none of these Russians were trained in statecraft is so true right now for us. Hence the bitter online feuds, public dramas and “crashing out” among the alleged leaders. We need armies of well versed men like Stephen Miller who is brilliantly using the laws and powers already in place to carry out the mission (not just complaining on Twitch and asking “Is this real, chat?”).

And you’re completely right that one more man can make a difference. I recall in the battle over masks at one of my kids’ school that there was a fierce debate about what to do about a new order from the governor. Most parents just wanted to bemoan their terrible fate or lately this or that abuse. But while they complained, I pulled up the governor’s order and suddenly found a loophole that could be exploited to get students’ masks optional without an official doctor’s note. I voiced this in an authoritative tone that implied I might be a lawyer, and the administration orchestrating the meeting took note. By the very next day, they had a “do it yourself” guide for parents about how to get an exemption with or without a doctor’s note. One man made a difference for hundreds of kids who might otherwise have been masked for six hours a day. I’m not that smart. But it was just one more set of eyes and the right tone to get a complete shift in the mentality. People moved from complaining about government overreach to how we could get the word out.