What was the role of Freemasons in the Russian Revolution?

Haven't you ever wanted to know?

I really dislike conspiracy culture. This is not always because the conspiracies aren’t true—in fact, often they have a high degree of truth to them. However, it seems like conspiracies have a habit of shutting down discourse rather than opening it up.

Culture is the problem in conspiracy culture. All of these ideas have entered the mainstream and they’re a lot of fun—high drama, sinister plans, the secrets of the universe, etc. However, as conspiracy culture has become popular with a wider range of people with a wider range of interests, the conspiracies themselves tend to take a back seat.

People care a lot less about whether or not what they’re saying is true these days. It goes beyond having earnestly held beliefs that are merely incorrect. After a certain point, discussing these politically charged topics just becomes a game. People accept anything on a whim (I consider this something separate from genuine belief) so they can participate in these games. However, for the reasons I laid out in my previous essay, when you offer any kind of alternative to this, it’s usually interpreted as a personal attack rather than a disagreement.

I wanted to illustrate what one conspiracy looks like by reproducing selections from a chapter of George Katkov’s book Russian 1917: The February Revolution. I read a lot of stuff about the Russian Revolution, but I don’t know that much about the February Revolution (which actually deposed the Czar) beyond the basic details. Katkov’s work is the best book I’ve found on this specific topic, beyond the ever-reliable Sean McMeekin’s more general (and generically named) book The Russian Revolution: A New History.

The February Revolution is often overshadowed by the October Revolution that occurred later that year. This is understandable as many of the events surrounding the February Revolution are opaque even today. The right hand frequently didn’t know what the left was doing. There also isn’t much action to accompany all of the tedious political and diplomatic maneuvering in and outside of the capitol.

Still, the story of the February Revolution is extremely interesting and probably more relevant to the problems we face today than all the later drama. The culmination of decades of treason by Russian liberals climaxed in a successful change of regime that was immediately stolen from them by the much savvier and more ruthless Bolsheviks.

Before you read this passage, it might be helpful to read (or listen to, the text-to-speech feature on the Substack app is very good) my Introduction to the Russian Revolution. I spend the overwhelming majority of time covering the events that followed the February Revolution, but I also provide a lot of background on the pre-Revolution political and social dynamics of the Russian Empire that could be helpful. As I said before, you should think of history as drawing a circle over and over again, adding little bits of somewhat overlapping information that eventually leave you with a much more robust circle.

This chapter from Katkov’s book deals with a very charged topic that frequently appears in conspiracy culture: Freemasonry. I don’t know very much about Masonry beyond knowing that many of the American Founding Fathers were Freemasons and having watched a very interesting Vichy French film Occult Forces (1943) that depicts (apparently accurately as the director was a former Freemason) French Masonic rituals during the Interwar period as well the Vichy/German occupation line on the alleged maneuvering of the Western Allies into a war with Germany by a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy (your mileage may vary with this part). The director was tried and executed by the French government for collaborating with the Germans after the war so he certainly pissed someone off. Anyway, Masonry is mysterious to me. People make a lot of claims about it and most of them seem pretty dubious, but Freemasons certainly were involved in many conspiracies, including during the Russian Revolution.

To give you some background knowledge and faming to help you understand the chapter better. The Progressive Bloc was an alliance of Russian liberals, socialists, and republicans in the state Duma (Russia’s parliament) who were committed to curtailing the power of the monarchy. They were supported in this effort (surreptitiously) by foreign powers, namely Great Britain. The Voluntary Organizations were a network of non-governmental organizations and civic associations that were set up by private parties (nobles, business leaders, local governments) to assist with Russia’s efforts in World War I.

The Voluntary Organizations took over numerous responsibilities typically handled directly by the government. They built hospitals for the wounded, attempted to address critical shortages of war material through the business sector, and even set up recreational clubs and other services for soldiers near the front lines. This degree of private intervention normally would not have been tolerated, but Russia’s military was not prepared for the enormous logistical strain of mobilizing and equipping millions of soldiers on relatively short notice. Patriotic wealthy Russians, with access to their own more nimble organizations and private resources, offered to lend a hand.

According to Katkov, the nominally patriotic Voluntary Organizations were largely compromised by the Progressive Bloc. Russian liberals wanted to assume control of critical sectors of the Russian war economy so that they could then use these strategic positions to undermine and extract political concessions from Czar Nicholas II. They could create shortages where none existed before. They could cause work stoppages through strikes and other administrative measures. They could place liberal activists near the frontlines to demoralize and radicalize soldiers.

In wartime, this kind of deliberate sabotage in order to achieve domestic political objectives constitutes high treason. However, the Progressive Bloc controlled a majority of the Duma and Czar Nicholas II’s ability to deal firmly with such a broad coalition of bad faith actors was limited.

The Voluntary Organizations clashed with the government several times, demanding personnel changes, before the government eventually cracked down on this behavior. After this firm split, the Progressive Bloc and the Voluntary Organizations began a smear campaign targeting members of the royal family and important officials, while also claiming (with no evidence whatsoever) that a “Black Bloc” of conservative officials surrounding Czar Nicholas II were secretly in the employ of Germany and attempting to sabotage the war effort. The only way to salvage Russia’s position in World War I, these people began to claim, was to remove the Czar.

There’s no English-language Wikipedia article for the Voluntary Organizations despite their significance. Within the conspiracy of the Progressive Bloc and the Voluntary Organizations was another conspiratorial group whose existence wouldn’t be confirmed until decades after the Russian Civil War: Freemasons.

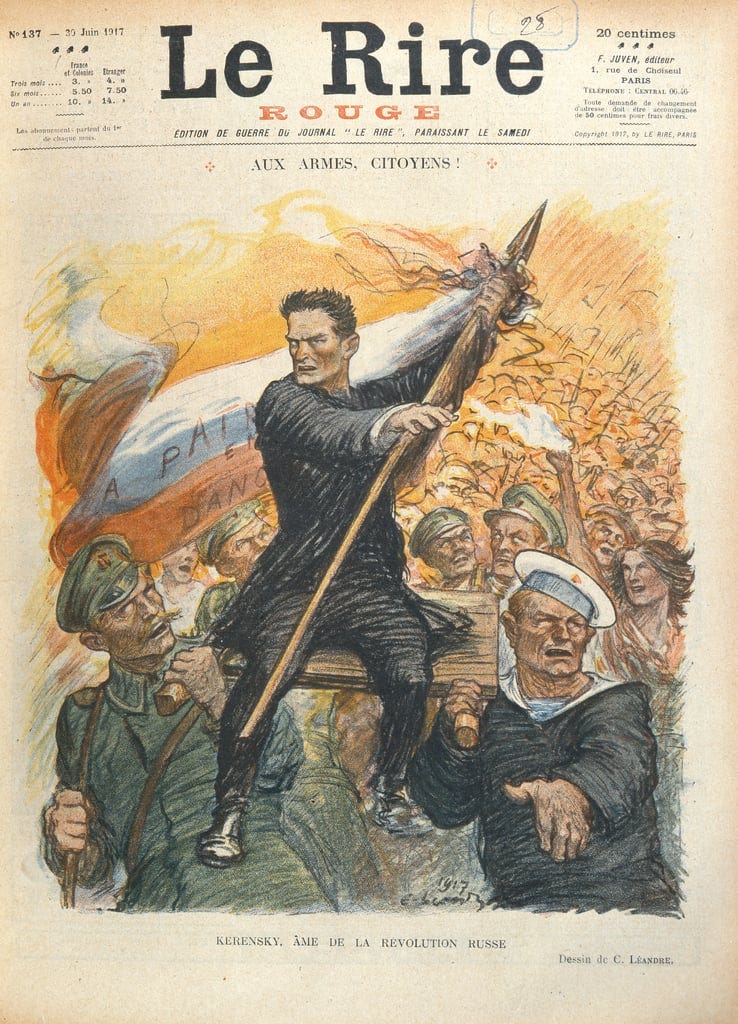

Many of the major figures within the Progressive Bloc and Voluntary Organizations were Freemasons, though most were not. According to Katkov, Alexander Kerensky, who would eventually come to lead the Provisional Government after the February Revolution as well as several of major ministers and cabinet officials who populated the Provisional government were members of a secret Masonic organization.

Although there was a great deal of speculation surrounding this organization for decades, there was virtually no hard evidence of its existence until the 1950s when one of its members, the prominent far-left social activist Yekaterina Kuskova (who was banished from Russia by the Bolsheviks shortly after the October Revolution), finally confirmed the group’s existence in a letter to a friend that was later published.

After the letter was published (and apparently after Katkov had written the below book, I’m still not sure how this happened but Kerensky’s confirmation came in 1965 yet received no direct acknowledgement in Katkov’s very thorough work in 1967), Kerensky confirmed his membership in such a Masonic organization, stating:

The proposal to join the Masons I received in 1912, immediately after being elected to the Fourth Duma. After serious reflection, I came to the conclusion that my own goals coincide with the goals of the society, and accepted this proposal. It should be emphasized that the society I entered into was not an ordinary Masonic organization. The first thing that was unusual was that the society broke all ties with foreign organizations and admitted women into its ranks. Further, a complex ritual and the Masonic system of degrees were eliminated; Only an indispensable internal discipline was maintained that guaranteed the high moral qualities of members and their ability to keep secrets. No written reports were made, lists of members of the lodge were not drawn up. This maintenance of secrecy did not lead to a leakage of information about the purposes and structure of the society. When I studied the circulars of the police department at the Hoover Institution, I did not find in them any information about the existence of our society, even in those two circulars that concern me personally.

This revelation is most useful because it clarifies why we have no evidence of the group’s existence: They apparently didn’t write anything down as a matter of policy and selected members based on their ability to keep a secret (rarer than you’d think). However, everything Kerensky says should be taken with a grain of salt.

Kerensky is perhaps the man most responsible for the fall of Russia to Bolshevism. It is hard to overstate how badly he mismanaged the situation following the February Revolution. He was, as General Wrangel described him, “Russia’s gravedigger.” From what I’ve read of Kerensky’s post-Revolution writing, it seems like he goes very far out of his way (perhaps dipping into fantasy) to present himself in a favorable light and his rivals in very unfavorable lights. He not only collapsed the Russian government through incompetence, but once he was in exile abroad actively attempted to sabotage the efforts of the White Army as it was in combat against the Bolsheviks, lobbying foreign powers to cut off military aid to the struggling anti-communist force.

Polish historian Ludwik Hass speculated in a very good article that the Russian Masonic movement had a mere 600 members in 1915, when the Russian Empire had a population of approximately 150 million. Although several Freemasons ended up rising to the top of the Provisional government, the overwhelming majority of active participants in the larger scheme to replace the Czar were not Freemasons and might not have known that there was a conscious deception at play or what objective, if any, they were working towards. Furthermore, it seems like the events of the February Revolution took the Masons themselves by surprise. Although they certainly were trying to undermine Russia’s government and replace it with something else (apparently some members of the Masonic conspiracy were monarchists [?]), they could not have predicted how events would unfold much less engineered them in any kind of precise way. There were major divisions even within the Masonic movement. Still, their clandestine organization and maneuvering left them far better positioned to capitalize on events as they unfolded.

Knowing what actual conspiracies look like I think acts as an antidote to popular conspiratorial thinking. There are lots of contradictions here: Serious historians reflexively denied the existence of a Masonic organization because of a controversial document that postulated a Judeo-Masonic conspiracy to take down Russia. However, it turns out that a Masonic conspiracy actually existed. However, this Masonic conspiracy was apparently conducted separately from other international branches of Freemasonry, jettisoning the ritual and spiritualism that people typically find most interesting about such groups. Also, the overwhelming majority of people working in pursuit of “the conspiracy” were not part of any organized plot in any meaningful sense. Most participants in the Voluntary Organizations were just normal Russian professional class people, many of them acting totally in good faith. Most members of the Progressive Bloc were just Russian liberals. They didn’t need to be told what to do and when they lied often didn’t know they were lying. The heavily Jewish-influenced Bolshevik Party (which could not even muster a majority of support from the Russian Empire’s Jews) that overthrew the Provisional Government was actually hostile to Freemasonry, formally banned Masonic groups, and exiled many major members of the Russian Masonic movement. However, even after the Bolshevik purge of Masonry, there were apparently still several secret members of the Masonic set who had managed to find their way into prominent positions in the Communist Party. Of course, all this is kind of speculative. We’re working off of incomplete evidence from witnesses who should be viewed skeptically. Anything that was really damning, if it ever existed at all, might have been destroyed decades ago.

Yes, there are many conspiracies that you can and should understand. However, the extent to which anyone is firmly in control or there’s a clear plan is often much more dubious. What I hope you take from all of this stuff is that actually you are in control, rather than sinister unknowable forces. None of these people or groups were invincible and nothing they did was inevitable. These groups are often very unimpressive once you dig into them.

A few notes when reading this selection: Who are the people mentioned in this chapter? There are a lot of names in here that even I don’t recognize having read a lot about the period. Look at the painstakingly recreated footnotes (Footnote 15 gives a great description of a confirmed government agent provocateur who made his way into the Kadet Party): I can’t read Russian and can’t verify that the work Katkov is citing actually reflects what his claim is, or if the underlying claim in the cited work is accurate. You’re working off of an incomplete picture that you shouldn’t get too invested in when you read about history without studying it extensively. That’s how all history is. People spend their careers studying these particular narrow topics. There’s always more to the story.

If you want to know why I have such a complex about conspiracy culture, it’s because in Russia during the revolutionary period one major problem was that people would just lie constantly, to the point where what they were saying no longer had any bearing on reality. Russians even had a term for this kind of lying: vranyë, which was “that special kind of imaginative lying which gives a picture of reality amended to suit some ultimate purpose and counts on ready acceptance by the deceived.” Once someone is overtaken by this behavior, they rarely stop.

Although many of these lies were pushed by sinister forces who had a grand plan, many of them originated for reasons that were purely petty and personal. People could not stop lying, resulting in a state of generalized hysteria that did an enormous amount of damage to Russia. Even if the originators of the lies had no conscious intent to deceive and no dubious motivations, in other words, if they were merely delusional, these lies provided ideal conditions for bad actors to carry out their work.

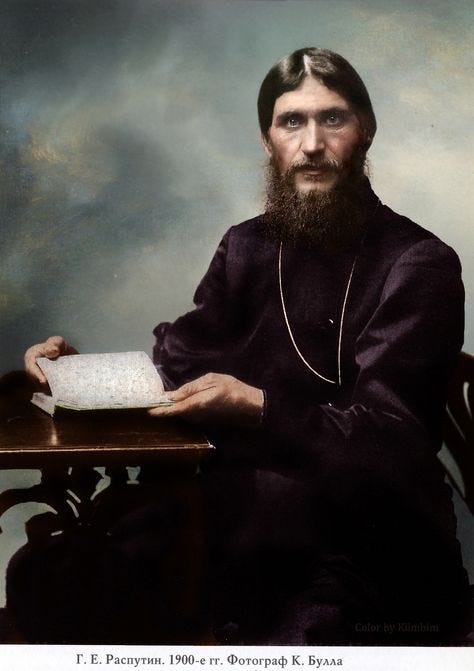

Anyway, after all that, here are the sections of Katkov’s book on the Freemasons. I’ve also reproduced a selection from the end of the chapter that deals with the assassination of Rasputin, just because that is such a hot (and very interesting) topic and if you’ve made it this far down you deserve a little extra.

****

[Begin selection pg 153]

Chapter 8

The Onslaught on the Autocracy

The start of the denunciation campaign; Russian political freemasonry; The Guchkov plot; 'The Mad Chauffeur'; Guchkov and the army; Milyukov's broadside; The Assassination of Rasputin

I. THE START OF THE DENUNCIATION CAMPAIGN

The August crisis ended in a stalemate between the monarchy and the 'progressive' forces represented by the Progressive Bloc and the Voluntary Organisations. This stalemate was to last up to the February revolution. After August 1915, no further attempt was ever made by the Council of Ministers to change the policy of the government and to direct it into the channels which Krivoshein, Shcherbatov, Sazonov, Samarin and their colleagues thought would lead to political co-operation between the government and the public.

On the other hand, the government did not resort to repressive measures either against the Duma or against the Voluntary Organisations as such. The Duma was expected to carry on the legislative activities necessary for the prosecution of the war, and the Voluntary Organisations continued to assist the Special Councils in the organisation of military supplies and the supervision of industry and transport. Surprisingly, in spite of the continuous friction between the Voluntary Organizations and the government and the steady deterioration of relations between the Duma and the Tsar, the system of Special Councils, in which the Voluntary Organisations took an active part, worked beneficially from the point of view of the war effort. The government felt that it could safely postpone a general reckoning with the Duma and the rebellious Voluntary Organisations until victory over Germany was won. All that was necessary in their view was to curb the political activities of the Voluntary Organisations and prevent their joining hands with the revolutionary movement.

But curbing the activities of ambitious and angry men was not an easy job, and the Voluntary Organisations repaid in kind all indignities inflicted on them by the government. When, for example, the government revealed its intentions by appointing a notorious secret police officer, Vissarionov, as inspector and official auditor for the Union of Municipalities, the Voluntary Organisations answered by threatening the government with popular unrest.

In his statement to the Muravyev commission the chairman of the Union of Municipalities, Chelnokov, revealed some of the methods used by the Voluntary Organisations to intimidate the government.1

During the war, the Moscow municipality decided to increase the salary of municipal employees by a total sum of two and a half million roubles. The government authorities in the person of the Governor of the City (Gradonachalnik) Klimovich protested against the decision of the City Council. Chelnokov, who was the Mayor of Moscow, issued an announcement that no salaries at all would be paid to the employees in view of the protest of the City Governor. He did so in spite of the fact that Klimovich had assured him that the matter could be cleared by correspondence between his department and the municipality, and that there was no reason to withhold payment of current salaries. Such was the pin-prick technique used by the warring parties in this incessant struggle for power and independence of decision. Much of the bad feeling between the imperial administration and the Voluntary Organisations—in this case the Union of Municipalities—was due to a natural departmental jealousy inherent in all bureaucratic systems. Four months after the February revolution the same Chelnokov was already at loggerheads with his political friends in the Provisional Government, and was accusing them of many of the same sins of which he had formerly accused the governments of Stuermer and Trepov.2

As soon as the attempt to establish a 'government of public confidence’ had failed, the liberals and radicals of all shades began to realise that they had been maneuvered into a position which would become indefensible, especially after a victorious end to the war. Their patriotic feelings, however, would not allow them directly to sabotage the war effort. But the temptation to use their steadily-increasing influence on the economic situation in order to embarrass the government and finally to overthrow it and so force the Emperor to appoint a 'government of public confidence' was too great for the liberals to resist: the whole future of the development of Russia towards a liberal, progressive, constitutional monarchy was at stake, and both the Duma politicians and the Moscow Voluntary Organisation centres understood this. Accordingly, they introduced a new note into their attacks on the government: instead of claiming, as they had done before, that the government was incapable of winning the war without their help, they now alleged that it was not working for victory at all, but was secretly preparing a separate peace and a shameful betrayal of the Allies.

These new tactics were adopted by the liberals in September 1915, as is clear from the reports of the secret police on the private meetings in Moscow which preceded the Congresses of the Zemstvo and Municipality. The Moscow secret police (Okhrannoe Otdelenie) was at that time headed by an intelligent and hard-working officer, Colonel Martynov, whose reports, which we have often quoted, were published together with other materials under the general supervision of Professor Pokrovskyin 1927.3

The liberals' activity in Moscow in mid-August took the form of a number of private meetings, the first of which was held in Konovalov's house on the 16th.4 Originally, the aim was to give the full support of the Voluntary Organisations to the newly-formed Progressive Bloc of the Duma and to its programme.5

The meeting at Konovalov's house elected a committee which would propagate the ideas of the Progressive Bloc in the country through the Voluntary Organisations.6 This was followed by a number of banquets and private meetings, at which the possibility of a liberal government and its composition were discussed. These preparatory conferences led to the passing of a resolution by the Moscow Municipal Duma addressed to the Tsar, asking for a 'government of public confidence', and suggesting that the Tsar receive a delegation which would present a 'loyal address'.

The proceedings of the Council of Ministers recorded in the previous chapter leave no doubt that the Moscow parleys were somehow coordinated with the disaffected ministers' efforts to induce the Emperor to change the composition of the government. Goremykin's resistance to all these pressures put an end to the hopes for a peaceful settlement between the Voluntary Organisations and the Progressive Bloc on the one hand, and the Tsar on the other. The removal of the Grand Duke from the Supreme Command was obviously considered a serious blow to the liberals' plans. (All of a sudden, the Moscow liberals discovered a warm spot in their hearts for the Grand Duke, who had never shared their views and whose military administration in the areas behind the front lines had shocked, by its reactionary arbitrariness and anti-Semitism, even the members of the Tsarist government.) But the decisive blow to liberal hopes was the closing down of the Duma, on 3 September, for the autumn recess. With it went the illusion that the formation of a 'government of public confidence' was imminent. The news reached Moscow a few days before the opening of the official congresses of the Union of Zemstvos and the Union of Municipalities.

The tactics on which the Moscow liberals relied in the middle of August had failed completely, and were now to be replaced by a different and spectacular line designed to impress and inspire the delegates to the congresses. On the eve of the opening of the Congress of the Zemstvos 6 September, a meeting took place in the house of the Mayor of Moscow, M. V. Chelnokov, attended by representatives of the Voluntary Organisations and the Duma; including Prince Lvov, Guchkov, Milyukov, Shingarev, Konovalov and many others. It was at this meeting, according to a report of the secret police, that a new explanation was given for the reactionary course of the government, and this became the basic presupposition of all liberal political activities in the course of the next eighteen months.7

Those present at this meeting discussed the latest events and expressed their belief that they were the work of a 'Black Bloc' whose aim it was to counteract the activities of the newly formed Progressive Bloc. This 'Black Bloc' was allegedly headed by pro-German circles at the Emperor's court and included the reactionary minority in the Council of ministers (i.e. Goremykin and A. A. Khvostov), as well as the rightwing parties of both legislative assemblies. It had succeeded, it was alleged, in isolating the Emperor from his patriotic advisers, in strengthening the position of Goremykin by replacing the Minister of the Interior, Shcherbatov, with such a ruthless bureaucrat as Kryzhanovsky,8 and in removing Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolaevich from the Supreme Command. Thus a situation would be brought about in which the Emperor had no alternative but to sign a separate peace with Germany.

The police report summarises the discussions at the meeting at Chelnokov's house:

The Emperor is a prisoner of the Black Bloc; he is held responsible on all sides for the unpreparedness of the Russian army, and the acceptance of the hypocritical proposals for the conclusion of a separate peace made by the Emperor Wilhelm hangs only on his decision. The conclusion of a separate peace is, indeed, the basic aim of all the efforts of the Black Bloc. ... For members of the Cabinet of the type of Goremykin or of Kryzhanovsky, a separate peace would be preferable to the victory of the Entente. A separate peace would not only secure Goremykin's personal position, but would also lead to a strengthening of the autocratic principle in Russia, while for statesmen such as Kryzhanovsky the fate of Russia is of no importance if only they can pursue their careers with éclat and success and live in the ephemeral triumph of their personal power .... The present government ... is obviously striving to sow discontent and to create general confusion, to cause a split between the Army and the people, ·and to bring about conditions under which it will be possible on the one hand to conclude a separate peace, and on the other to use the Army, which will resent having been abandoned by the country in the face of the enemy, to quell internal unrest.

In view of the existence of this powerful 'Black Bloc' conspiracy, it was decided at the meeting: (a) to keep a cool head and avoid all internal disorders, which would only help the enemy—that is, the 'Black Bloc'—to carry out its 'hellish intentions'; (b) to resume the work of the legislative assemblies in order to secure an opportunity to expose the government, which could carry out its wicked plans only if they were concealed from the people; and (c) to 'establish a government vested with public confidence in order to wrest power from the hands of those who are leading Russia to its destruction, to slavery and shame'. It was also decided to issue an appeal to the population for the maintenance of order and of solidarity with the heroic army, to approach the monarch in order to 'open his eyes', and to put certain demands to him. Should these demands of the people not be satisfied by the Tsar, 'both he and the people would regain their freedom of action and remain for ever estranged'.

The police report closes with the following note:

From the morning of 7 September, and in the course of the next twenty-four hours, members of the congress who were genuine representatives of the Zemstvo and Municipality self-governments of the Empire were acquainted with all the findings established at the preparatory meeting in the residence of Chelnokov. These revelations are producing a shattering impression on the members of the congress. General indignation is growing steadily.

The police report must have appeared rather fantastic to the officials of the Ministry of the Interior to whom it was addressed. The idea of a Black Bloc was indeed a figment of the liberals' fevered imagination. Nevertheless it provided the leitmotiv for the propaganda campaigns which were launched and sustained by the liberals from the September congresses of 1915 up to the February revolution of 1917. It is difficult to imagine that the responsible politicians who gathered at Chelnokov's residence could really believe in the existence of the 'Black Bloc'. The police report sheds no light on the origin of this belief, nor has any evidence in support of it ever been adduced by those who held it. But at the same time it does appear that responsible politicians were genuinely convinced that powerful forces close to the throne were working for the conclusion of an immediate separate peace. Rodzyariko held fast to this conviction to his dying day, but he could never give his reasons for it. The legend spread to left-wing circles and became an article of faith in Soviet historiography when—in the twenties—the historian and archivist, Semennikov, showed much ingenuity in trying to make it plausible as a historical hypothesis. At the Moscow State Conference in August 1917, the leader of the right-wing Social Democrats, Tseretelli, claimed that had there been no February revolution Russia would by that time already have concluded a shameful separate peace with Germany.

Under the Provisional Government, the famous Muravyev Commission for the Investigation of the Crimes of the Old Regime looked carefully into the cases of the high state officials who were suspected of having belonged to the 'Black Bloc' and to the pro-German circles in Russia. The seven volumes containing the proceedings and the brilliant memoir on the end of the Tsarist regime by the poet Alexander Blok, who served as a secretary of this Commission, show clearly that great as the shortcomings, corruption and decrepitude of the regime may have been, there was no such thing as a German party or even a defeatist movement among the Tsarist bureaucracy, not even among the shady characters who were trying to push themselves into positions of favour and influence at court.

Nor do the documents of the German Foreign Ministry made available after World War II indicate any contacts between the German government and the supposed pro-German party at the Russian court or within the government.9

If the police report is to be believed, no mention was made at the meeting at Chelnokov's house of the part played by the Empress in the pro-German party. This, however, soon became the main feature of the 'legend of the separate peace', which spread through the country long before P. N. Milyukov lent it support in his famous speech of 1 November 1916. The supposed connection of the 'German woman' (nemka) with efforts to force the Emperor to conclude a separate peace was probably the most destructive charge levelled by opposition circles in 1916. We have full proof now, after the publication of the Empress's letters to her husband, that there was no truth whatever in these allegations.

In one of the best studies on pre-revolutionary developments in Russia, the emigre historian Melgunov, himself a Popular Socialist; carefully examined all the sources of the legend.10 His findings were more explicit, but no less negative, than those of the Muravyev Investigation Commission. The question for the historian now is, therefore, not whether this legend is true or not, but rather why, if it had so little factual basis, it was so readily believed by the public and so eagerly fostered by people who had every possibility of checking its veracity. The answer is simple, although not much to the credit of those who based their appeal for popular support on the exploitation of this rumour.

As we have seen, stories of high treason had spread widely as soon as the reverses at the front occurred in 1914-15. They grew even more persistent as the shortage of arms and ammunition became known to the public. The announcement of Myasoedov's trial and execution and the retirement and impeachment of the Minister of War, Sukhomlinov, were taken by the public as irrefutable confirmation of treason in high places. The leaders of the liberal opposition must have been impressed by the powerful impact of such rumours on public opinion and must have realised that these could become an effective weapon in their struggle for political reform. It was therefore clearly to their advantage to launch, early in September 1915, a second wave of treason rumours, alleging the existence of a 'Black Bloc', as soon as their hopes for a reform by agreement with the government had been frustrated.

The slanderous accusations against Goremykin of promoting a separate peace were not voiced in the official meetings of the congresses, which passed resolutions demanding a 'government of public confidence' and elected delegates who would present these resolutions to the Emperor.11

Nothing came out of the projected delegation to the Tsar. Nicholas II refused to receive the delegates of the congresses, who were instead summoned to appear before the Minister of the Interior and were told that, while the work of the Voluntary Organisations for the army was greatly appreciated, their interference in general state affairs could and would not be tolerated. Prince Lvov argued with the Minister of the Interior Shcherbatov, insisting on an audience with the Emperor, but before Shcherbatov could give an answer, he was replaced as Minister by A. N. Khvostov ('the Nephew'), with whom Prince Lvov had no further dealings. Instead, Lvov wrote the Emperor a long winded, sanctimonious letter harping relentlessly on the theme of a ‘government of public confidence’, which as far as we know remained unanswered.

The tone and content of Prince Lvov's letter explain why his approach to the Tsar had so little success. Pompous in its archaic language, it is vague and utterly disingenuous in its wholesale accusations against the 'government'. In it he affected to believe that the government, in resisting the demands of the liberals, was disobeying the orders of the Tsar—something which he knew very well was absurd. Here is a shortened version of this piece of Byzantine rhetoric:

Your Imperial Majesty! We, the elected representatives of the Zemstvo and Municipalities of Russia, have been delegated to tell you the living truth. When the storm of war broke over Russia, from the height of your throne, you appealed for the unity of all the forces of the country and for the abandonment of all internal strife and quarrels. The country responded, doing justice to the true strength of the Russian people. In the depths of the popular masses, Sire, fresh strength is constantly gathering, and the spirit of liberation is moving above us. The great reforms of Alexander II have laid the foundation of self-government, and you, Sire, the grandson of the Liberator-Tsar, have called popular representatives to reform the state. The war has developed the state power of the Russian people, which is becoming stronger under the heavy blows we have suffered. The powerful and impressive picture of the unity of all forces in Russia has become apparent to the whole world. Both our allies and our enemies have learned to see it, but, to the greatest misfortune of our Fatherland, our government refuses to recognise it.

The government alone has not followed the path indicated from the height of the throne. At the time when our army was forced to retreat for lack of ammunition, abandoning to the enemy Russian land soaked in the precious blood of its people, the government, in its jealous suspiciousness, saw in the highly patriotic popular movement a threat to its power, as if what mattered was that power and not the integrity, greatness and honour of Russia. The internal economy of the state is totally disrupted, and its chaotic condition threatens the cause of victory, yet the war does not seem to exist as far as the government is concerned. State power should, at such a time, correspond to the spirit of the people, should grow out of it, as a living plant grows from the earth.

Your Imperial Majesty, Russia looks to you in these fatal years for a sign that the supreme power is achieving greatness by acting in unity with the spirit of the people. Restore the great features of spiritual unity and harmony in the life of the state, distorted by the government! Bring new life to state power; entrust its heavy responsibilities to persons who will be strong because they possess the confidence of the country! Renew the work of the people's representatives! Open to the country the only way to victory, which has been obstructed by the lies of the old order of administration! ... The government has brought Russia to the edge of an abyss. In your hands is her salvation.12

One wonders if it is not under the impression of reading such texts as the Lvov letter that forty years later Pasternak could write, referring to this period of Russian history:

It was then that falsehood came into our Russian land, and there arose the power of the glittering phrase—first Tsarist, then revolutionary .... Instead of being natural and spontaneous as we had always been, we began to be idiotically pompous with each other. Something showy, artificial, false, crept into our conversation—you felt you had to be clever in a certain way, about certain world-important themes.13

The cold-shouldering of the Voluntary Organisations by the Emperor and his government strengthened the left-wing tendencies in them and made their leaders look for other methods of achieving their political aims than the passing of resolutions and requests for audiences with the Tsar. From then on, an unrestrained campaign of denunciation against every statesman and politician who was ready to serve in the government was launched in the press. At the same time, a number of private committees of a more or less clandestine character were farmed to consider ways and means of bringing direct pressure to bear on the Emperor, or even of engineering a palace coup.

2. RUSSIAN POLITICAL FREEMASONRY

The formation of a new secret society connected with and modelled on masonic lodges probably took place at this time. The part played by political freemasonry in the preparation of the February revolution has been, until very recently, a secret closely guarded by all concerned. The whole question has been largely shunned by historians because of the repugnance aroused by the theory, so popular in the twenties in reactionary circles all over the world, of a ‘Judaeo-Masonic World Conspiracy'. Here again, a popular conception based on a notorious forgery (the Protocols of the Elders of Zion) has effectively discouraged legitimate historical research in an important field of clandestine political activities, just as the forgeries known as the 'Sisson Papers' retarded investigation of the undercover intervention of German agents in Russia in 1917.14

The revival of masonic activities in Russia goes back to the period after the 1905 revolution, when a number of lodges (the 'Northern Star', the 'Regeneration' and others) were formally constituted in Russia by emissaries of French freemasonry. An important part was played in this movement by the Petrograd lawyer M. S. Margulies and the notorious Prince Bebutov, who had been a member of the Kadet Party and a deputy in the First Duma.15 When, as a result of an exposure in the press, the 'Northern Star' was forced to 'go to sleep', there seems to have been a temporary cessation of masonic activities. After the breakdown of the negotiations between the Progressive Bloc and the government in September 1915, the need for a clandestine organisation which would infiltrate every sector of national life became urgent in the eyes of the liberals and radicals. In fact, an organisation named the 'Committee of Public Safety' seems to have been planned in the early days of September. Thus, a remarkable document published in Krasny Arkhiv, XXVI, and alleged to have been found among the papers of Guchkov, is signed 'Committee of Public Safety'. It is entitled 'Disposition No. 1' and is dated 8 September 1915. The document claimed that there were two wars going on in Russia, one against the Germans, the other—no less important—against the 'internal enemy'. A victory over the Germans could not be won before the defeat of the internal enemy (that is, the forces of reaction supporting the autocratic regime). Those who realised the impossibility of any compromise with the government were called upon to form a 'general headquarters', to consist of ten men chosen for 'the honesty of their work, the firmness of their will, and their belief that the struggle for the people's rights must be carried out according to the rules of military centralisation and discipline'. The methods of struggle for the people's rights would be peaceful, but firm and skilful. No strikes, which were damaging to the interests of the people and the State, would be tolerated. People who did not comply with the directives of the committee of ten were to be 'boycotted', i.e. ostracised by all patriots and hounded out of public life. Three persons were named as the nucleus of the headquarters for the struggle against the 'internal enemy'. These were Prince Lvov, A. I. Guchkov, and A. F. Kerensky. Guchkov was described in the document as the man who possessed the confidence both of the army and of the city of Moscow, 'which has now become not only the heart but the centre of Russia's will power'.

Melgunov,16 in referring to this document, seems nonplussed. What is it, he asks. A mystification? A police invention? The fruit of the idle fantasy of an amateurish organiser of projects? In his perplexity Melgunov turned for an explanation to Guchkov and Kerensky, and both denied the possibility of such an association in 1915. Kerensky claimed to have met Guchkov only after the revolution, and to have made the acquaintance of Prince Lvov for the first time in the autumn of 1916. This, on the face of it, should be a warning to historians against using this document. Quite recently, however, new evidence has come to hand. Among the documents of the German Foreign Ministry we find the report of a certain A. Stein, who was none other than the Estonian nationalist Alexander Kesküla,17 one of the principal agents of the German Revolutionierungspolitik in Russia.18 On 9 January 1916, he wrote to his contact on the German General Staff, reporting on some 'highly interesting revolutionary documents from Russia' which he wanted to be sent to Lenin.

One of these documents [writes Kesküla] . . . the product of a Moscow 'Committee of Public Safety' - suggests a dictatorial Directorate for Russia, to consist, among other people, of Messrs. Guchkov, Lvov, and Kerensky [sic!], which is extremely amusing. Judging by its comicosentimental torrent of verbiage, this must be a call from the right wing of the so-called Popular Socialists.

The document referred to by Kesküla is without doubt the same as that published in Krasny Arkhiv, XX.VI. It must have been picked up in Russia by Kesküla’s emissary, Kruse, who travelled there in the autumn of 1915.19 The dating of 'Disposition No. I' is, therefore, probably correct. As Melgunov rightly recognised, the document, in spite of its 'torrent of verbiage' (and possibly even because of it), accurately reflects the mood of Moscow opposition opinion in 1915. It is prophetic in its reference to a governing body consisting of ten members including Prince Lvov, Guchkov, and Kerensky: this was indeed to be the composition of the first Provisional Government. The historical importance of 'Disposition No. 1' is due not so much to its evidence of the existence of a 'Committee of Public Safety', which might have been only a pipedream, as to the fact that its general ideas were known not only to its anonymous authors but also to the Bolshevik revolutionary movement abroad, including Lenin himself, as well as to the German General Staff and the German government, who were instrumental in conveying it to Lenin. It was also probably known to Guchkov, even if he was not one of its authors, for we have no reason to doubt the statement of the Soviet archivists who claimed to have found it among his papers.

The denials of those named in this document, despite Melgunov's efforts to draw them out in 1931, are surprising.20 But these denials confirm the general impression that the political plans worked out and discussed in liberal circles in the period between September 1915 and the February days were conspiratorial, and that those who took part in them were bound to secrecy by some kind of solemn pledge. Indeed, there is a conspicuous gap in the memoirs on this period. Neither Guchkov himself, nor his close collaborator of the time, Konovalov, nor the two left-wing Kadets Tereshcheriko and Nekrasov—who were ministers through practically all the permutations of the Provisional Government—have published any comprehensive memoirs concerning this period. A. F. Kerensky, who has provided us with a considerable body of historical evidence in a number of volumes of reminiscences, has—as yet—cast very little light on the political developments preceding the formation of the Provisional Government. This silence of the politicians concerned is all the more suspicious in that discretion and reticence have never been a characteristic feature of Russian liberals. It naturally aroused the curiosity of Melgunov, who summarised in his book on the palace coup21 all that was then known of the existence of secret organisations in this period. Melgunov points to the affinity in style and content of 'Disposition No. I' with masonic political jargon, and suggests that it was related to the resurgence of the masonic movement in 1915. However, what Melgunov said in the thirties was not conclusive. The existence of a politically significant masonic movement on the eve of the revolution was far from proven. The veil of secrecy was first lifted with the publication of the memoirs of Milyukov in 1956.

Milyukov alleges that four members of the original Provisional Government,

all of them widely differing from each other in character, in their past careers, and in their political roles, were bound together, not merely by their radical political views. Besides that, there was between them some kind of personal bond, not purely political, but of a politico-moral character. They were also bound by certain mutual obligations coming from one and the same source...

And Milyukov closes with a disconcertingly cryptic remark:

From the above hints, one can infer what was the kind of bond that united the central group of the four ministers. If I do not speak of it in clearer words here, this is because, in observing the facts, I did not at the time realize the reasons for them, and learned about them by chance much later, when the Provisional Government had ceased to exist.22

Milyukov's guarded revelation must have caused a considerable stir among the former members of the masonic movement of 1915 still alive in emigration. In 1957, Kerensky visited one of the active members of this group, Mme Kuskova, in Switzerland.23

In a letter dated 20 January 1957, Mme Kuskova confided to her friend, Mme Lidia O. Dan:

I spent the whole of Friday with Kerensky. We had to discuss what is to be done about Milyukov's mentioning of that organisation of which I told you…. He very much approved what I had done: to write it down for the archive and to keep it safe for another thirty years. He himself will do the same. Moreover, he will answer the nebulous remark of Milyukov in the preface of the book he is writing. He will answer on his own behalf, without mentioning any other name. All this has been carefully thought out, and we agreed on the form in which information should be given. But what should be stopped, if possible, is the gossiping in New York: there are still people alive in Russia—very good people indeed—and one should have consideration for them.

In two further letters, one addressed to N. V. Volsky of 15 November 1955, and the other to L. O. Dan of 12 February 1957 (both are published in Aronson's book, quoted above), she gives details on the organisation itself.

Although she links the movement with the revival of freemasonry after the 1905 revolution—a revival which others have attributed to the influence of French freemasonry—she claims that the Russian masonic movement had no connection with any foreign organisation. It had a purely political aim—to restore, in a new form, the Union of Liberation,24 and to work underground for the liberation of Russia. Its immediate aim was to penetrate the higher bureaucracy, and even the court, and to use them for revolutionary ends. The whole masonic ritual was abolished; women were admitted to the lodges; there were no aprons, no paraphernalia; and the initiation had only one purpose: secrecy and absolute silence. The lodges numbered only five members each but there were congresses. Their oath was to complete secrecy. On leaving the movement, a member had to renew his oath of absolute silence. 'The movement was enormous', writes Kuskova in her letter to Volsky of 15 November 1955.25

Everywhere we had 'our' people. Such associations as the 'Free Economic Society' and the 'Technical Society' were totally penetrated .... Up to now the secret of this organisation has never been divulged, and yet the organisation was enormous. By the time of the February revolution, the whole of Russia was covered with a network of lodges. Here in emigration there are many members of this organisation, but they all are silent. And they will remain silent because of the people in Russia who have not yet died.

And in a letter of 12 February 1957 to L. O. Dan (the widow of the Menshevik Theodore Dan and sister of Martov) Kuskova elaborates further:

We had to win over the military. The slogan was: 'a democratic Russia, and don't shoot at the demonstrating people'. It needed much and long explanation .... Here we achieved considerable success.

We had to take over the Imperial Free Economic Society, the Technical Society, the Institute of Mining, and others. This was brilliantly carried out: we had 'our' people everywhere. A large field was opened to propaganda.

It is surprising that such a widespread organisation was neither discovered nor penetrated by the agents of the secret police. At least, there is no indication of it in the secret police material published by Soviet archivists. This is probably due to the short period of existence of the politico-masonic movement and to the depressed state of the Tsarist secret police under the leadership of such people as Prince Shcherbatov, the semi-demented A. N. Khvostov, and the unprincipled Beletsky.

It may well be that the temperamental Mme Kuskova somewhat exaggerated in her letters the importance of the masonic movement to which she belonged before the revolution. But, on the whole, everything she says tallies with what we know of the political development of Russian liberal and radical circles preceding February 1917. Neither the Kadet Party as such nor the Voluntary Organisations, the Unions of Zemstvos and Municipalities, nor the Central WIC were inclined to support the revolutionary movement. But everywhere inside them there were active minorities which carried on revolutionary propaganda and incited the leadership to action for the overthrow of the Tsarist regime. In the Kadet Party organisation this role was played by such people as the Duma deputy Nekrasov and the lawyers Margulies and Mandelstam. This same Margulies was Deputy Chairman of the Central WIC, dealing in particular with medical and sanitary supplies for the army.26 Gradually these people began to dominate the Voluntary Organisations. At the very time when the congresses of Zemstvos and Municipalities closed their sessions in September 1915 with unanimous hurrahs for the Tsar, there were people present who were carrying out a relentless propaganda campaign against the Tsar, his family and his government.

We shall not know what the structure of the masonic lodges was, nor what the congresses of the movement decided, until the members of the movement publish the masonic archives, if they are extant. It is clear, however, from the available material that the nucleus of the movement consisted, in 1916, of the four persons whom Milyukov mentioned in his memoirs: A. F. Kerensky, M. I. Tereshchenko, N. V. Nekrasov and A. I. Konovalov, later joined by the Duma deputy I. N. Efremov. The military branch of the movement seems to have been headed by the Duma deputy Count Orlov Davydov, who had been connected with the masonic movement from its beginnings in 1905 and was at one time in close contact with the notorious Prince Bebutov. Orlov Davydov was one of the richest landowners in Russia and maintained close relations both with Kerensky and with Grand Duke Nikolay Mikhailovich, a cousin of the Tsar and the author of competent works on Russian history.

What attracted this motley group to the masonic movement in Russia? With due reservations, I am tempted to explain it by psychological factors. Patriotism and public-spiritedness, especially among the upper classes, had its roots in the mystique of the monarchy and the belief in the divinely-inspired wisdom of the Tsar. As this mystical belief weakened and vanished under the onslaught of radical propaganda, freemasonry provided a substitute which an empirical and utilitarian approach to politics would not have afforded. It is characteristic that the emotional and idealistic mind of a Kerensky, inclined to a typically Russian brand of superstition, was won for freemasonry, whereas Milyukov is reported to have resisted all attempts to recruit him with the simple words: 'No mysticism, please'. As far as the military and the higher bureaucratic and court circles were concerned, freemasonry had, of course, a snob value. It also gave them opportunities to take part in political events by rendering more or less important services to politicians 'fraternellement', without the risk of being compromised in 'the dirty business of politics'. Apart from any direct influence on political developments in Russia, the effect of masonic ties on the morality of Russian politics should not be underestimated. The division between the initiated and the uninitiated cut straight across all party boundaries. Party allegiances and party discipline had to yield to the stronger tie of the masonic bond.

The Kadet Party suffered most from this division. When the moment came to organise a Provisional Government, the decision was taken not by the party committees, but under the influence of masonic pressure groups.

Kuskova claimed that the movement pursued a revolutionary aim, and Milyukov implied that the freemasons' blueprint for the political changes in Russia was solidly republican.27 All this, however, requires elucidation. Was the masonic movement in favour of a popular rising in wartime, in complete contrast to the avowed programmes of all defensist parties? This is hardly credible. Even Kerensky, in the autumn of 1915, advised the workers to stop the strikes. And, again, the outbreak of a popular rising of such dimensions as that of February 1917 seems to have taken masonic circles by surprise, as it did everyone else. The political tactics on which the masons relied were the same as those of the Voluntary Organisations—that is, gradually to oust the Tsarist bureaucracy from the vital controls of the war economy, and to replace it with members of the Voluntary Organisations. When control of the country's economic life had passed completely into their hands they expected that political changes would follow more or less automatically. Before leaving this subject, we must go back to one aspect of the Kuskova revelations which is somewhat sinister. We have seen that the main motive for keeping the history of the political freemasonry movement secret was, for Kuskova and her friends, the personal security of people who had belonged to the movement and were still living in the Soviet Union. Among these, according to Kuskova, were very prominent members of the Communist Party, two of whom were known to her by name.28

When the October revolution broke out, Prokopovich and Kuskova believed that the activities of the freemasons would be exposed, because the Communist Party would not tolerate the participation of its members in secret societies. Freemasonry associations were, indeed; declared illegal in the Soviet state. This imposed, in the eyes of the freemasons in emigration, a duty to keep quiet about the movement. With due respect for the scruples of the emigre masons, we may well doubt the efficacy of such precautions. We believe that the Cheka and its successors will certainly have uncovered all the secrets of the ex-masons in Russia, including those who were also members of the party. If they did not publicly expose them it must have been because they did not consider it expedient from the point of view of the party and the state. Perhaps even the contacts which, Mme Kuskova hints, she managed to maintain with 'the brethren' in Russia were used for their purposes by the Soviet security service.

3. THE GUCHKOV PLOT

No where was the influence of the masonic movement of greater importance than in the preparation of a coup d'etat to put an end to the reign of Nicholas II. Mme Kuskova denies that the freemasons as such supported the plot for the palace coup which Guchkov and his collaborators were planning. She admits, however, that Guchkov was a freemason, and that the movement knew of his plot but disapproved of it to such an extent that the question of his expulsion was raised. All this sounds very confusing, but the truth is probably much simpler than it appears from the Kuskova letters.

The masonic movement was predominantly republican; Guchkov was a monarchist. He wanted to overthrow Nicholas II in order to consolidate the monarchy, in which he would then become the leading influence. Neither the methods nor the ultimate aim of Guchkov were typical of those freemasons who were to form the nucleus of the Provisional Government, and who, as a matter of fact, were to jettison Guchkov soon after its formation. However, as Mme Kuskova admits, the freemasons were trying to win influential government, society and court support for the cause of the revolution; and many important bureaucrats and persons belonging to high society became involved in the movement. It is obvious that the penetration also went deep into army circles, particularly among the Guards officers, one of whom—General Krymov—was to play an important part in Guchkov's projected plot.

This is where masonic links were of paramount importance for Guchkov, and he no doubt used them to the fullest extent.

In spite of Melgunov's acute analysis,29 we still have few details of the practical arrangements made by Guchkov for his coup. Our chief source of information remains Guchkov' s cautious and reticent deposition on 2 August 1917, at a hearing of the Muravyev Comssion.30 Guchkov claimed that plans for his coup d'etat were drawn up long before the end of 1916, but he did not specify the date and refused to name his fellow-conspirators. The coup, as he had planned it, was to consist of two independent actions, involving the participation of a restricted number of army units. The first action was to stop the imperial train on one of its journeys between Tsarskoe Selo and GHQ at Mogilev, and there force the Emperor to abdicate. Simultaneously a military demonstration of the troops of the Petrograd garrison would have taken place on the pattern of the Decembrist rising. The existing government would have been arrested, and there would have been a simultaneous announcement of the list of persons who would head the new one. Guchkov believed that his rather fanciful variation on the old theme of a palace coup would have been welcomed in the country with enthusiasm and a tremendous sense of relief.

As far as the part allotted to officers was concerned, Guchkov was extremely evasive in his deposition. It so happened, however, that only four weeks later one of the officers involved—General Krymov—committed suicide in connection with the Kornilov Affair. His death produced a shattering impression on his friend, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tereshchenko. In an interview given to the press at the beginning of September, Tereshchenko disclosed that Krymov had taken part in the plot to carry out a palace coup. Guchkov categorically denied Krymov's participation in the plot, but there has never been rejoinder from Tereshchenko to elucidate this very important point.31 What is beyond doubt is the fact that before February, Krymov, both at the front and on his visits to Petrograd, where he met a great number of people connected with the Duma, kept insisting on the necessity of removing the Emperor in order to save the monarchy. This is explicitly stated by Rodzyanko in his memoirs.32 Krymov's link with Tereshchenko, on the one hand, and Guchkov, on the other, is a strong indication of the existence of a masonic bond between them. We can safely assume that Guchkov's efforts to penetrate the ranks of the army and Guards officers and to recruit supporters for his plot were based on masonic ties.

Later, as an emigre in Paris, Guchkov lifted another corner of the curtain which conceals the secret history of the conspiracies behind the abortive palace coup. In his memoirs published posthumously in a Paris emigre newspaper in 193633 he discloses the political combination behind the plot. He recalls having taken part in September 1916 in a secret meeting at the home of the Moscow liberal M. Fedorov, at which Rodzyanko, Milyukov and a number of other members of the Duma Progressive Bloc were present. The possibility of a revolution in Russia was discussed, and the prevailing opinion was that it was impossible for patriots to take part in a revolution during the war; they should not give up their efforts to obtain a government of public confidence by purely legal means. Should, however, a popular movement break out and street disorders occur the liberal patriots should stand aside until the period of anarchy was over, when they would doubtless be invited to constitute a government as the only alternative to the Tsarist ministers with any experience of state affairs. At this meeting Guchkov claims to have sounded a discordant note by arguing that this was pure illusion, that if the liberals let the revolutionaries organise the overthrow of the Tsarist government, they would never be able to seize power themselves. 'I fear', he said, 'that those who make the revolution will themselves head the revolution.'

Shortly after this meeting Guchkov was visited by the left-wing Kadet Nekrasov who had heard his statement and came to enquire whether Guchkov had any projects of his own to forestall a popular rising and to enforce a constitutional change by other means. Complete identity of views on this point was established, and from then on Guchkov, Nekrasov and Tereshchenko (who was then Chairman of the important regional WIC in Kiev) worked together in order to find a group of officers who would waylay the imperial train at a station between the capital and GHQ and force the Emperor to abdicate.

Guchkov's plot was certainly not the only one which was being hatched at that time, but it was probably the one most advanced by the spring of 1917. Guchkov himself admits that, had the revolution not broken out in February, his coup would have taken place in the middle of March. But although the plot did not come to fruition the effect of the Moscow conspirators' systematic assault on the loyalty of senior officers· in the Russian army should not be underestimated. On the one hand the commanders-in-chief of the various fronts and the Chief of Staff were gradually introduced to the possibility of the Emperor's abdication, and when the moment came and pressure was applied to them by Rodzyanko to help bring this about, they gave hint their support.

On the other hand the recruiting campaign of the conspirators among younger officers must have shaken their allegiance to the person of the monarch, and this may explain their disaffection during the rising of units of the Petrograd garrison on 27 and 28 February. Little has been revealed of the motives for their behaviour during the mutiny or of their clandestine contacts with Guchkov. It is significant that the young Prince Vyazemsky, who had been touring the barracks and strategic points in the capital with Guchkov on the night of 1-2 March, was killed, allegedly by a stray bullet, in circumstances which remain mysterious.

Guchkov claimed that the success of his coup depended on a favourable mood in the country as a whole and, in particular, on its acceptance by the army. He confidently expected an enthusiastic reception of the change of regime, even if it were brought about by the use of violence against 'the sacred person of the monarch'. In his deposition, Guchkov made the surprising remark:

You must bear in mind that there was no need for us to make propaganda or to persuade people. There was no need to prove to anybody the rottenness of the old regime and to demonstrate that it was heading for disaster. But we had to organise the technical side of things and to drive people to make this decisive step.34

Guchkov's remark does not mean that he himself, and the leaders of the Voluntary Organisations who were fighting the Tsarist regime on parallel lines, had not made an enormous propaganda effort throughout the preceding months, an effort which was certainly crowned with success, though the efficacy of the 'technical' preparations remains doubtful. Guchkov himself had been instrumental in organising and spreading the propaganda which was to discredit the Tsar and persuade the people that the war would inevitably be lost if there were not an immediate change of regime.

4. THE MAD CHAUFFEUR

This propaganda had to be conducted in the face of government vigilance and stringent wartime censorship, and it also had to surmount the obstacle of traditional loyalty among wide sections of the population, especially in the officer corps. Moreover, the situation at the front had improved considerably, and the success of Russian arms in Turkey in the autumn of 1915, and on the Austrian front in the Summer of 1916, had shown that the panicky mood which had seized public opinion after the reverses of 1915 had been due to exaggerated rumours and a general nervousness. It was clear that, despite everything, the existing government machinery could stand the colossal strain of the war effort for a few more months. Of course the propagandists of the liberal and radical opposition groups attributed the improvement in the war situation in 1916 to the efforts of the Voluntary Organisations and the patriots of the Army. But they insisted that this had happened despite the policy of the government, which was under the influence of 'dark forces'.

This propaganda assumed an almost hysterical character as time went on; slanderous, irresponsible accusations were flung by the liberals in the face of anyone who refused to support their cause in the struggle on the inten1al front. The articles which affected public opinion most were not those quoting specific instances of shortcomings and abuses by officials, but those which, in thinly disguised Aesopian language, attacked the existing system as a whole.

The press campaign became particularly acute in September 1915, at the time of the congresses of the Voluntary Organisations. Highly representative of this type of propaganda was the famous fable (published in No. 221 of Russkie Vedomosti, September 1915) by Vasily Maklakov, a reasonable and moderate leader of the Kadet Party. Here is a slightly shortened version of it.

A Tragic Situation

. . . Imagine that you are driving in an automobile on a steep and narrow road. One wrong turn of the steering-wheel and you are irretrievably) lost. Your dear ones, your beloved mother, are with you in the car.

Suddenly you realise that your chauffeur is unable to drive. Either he is incapable of controlling the car on steep gradients, or he is overtired and no longer understands what he is doing, so that his driving spell doom for himself and for you; should you continue in this way, you face inescapable destruction.

Fortunately there are people in the automobile who can drive, and they should take over the wheel as soon as possible. But it is a difficult and dangerous task to change places with the driver while moving. One second without control and the automobile will crash into the abyss.

There is no choice, however, and you make up your mind; but the chauffeur refuses to give way ... he is clinging to the steering-wheel and will not give way to anybody .... Can one force him? This could easily be done in normal times with an ordinary horse-drawn peasant cart at low speed on level ground. Then. t could mean salvation. But can this be done on the steep mountain path? However skilful you are, however strong, the wheel is actually in his hands—he is steering the car, and one error in taking a tum, or an awkward movement of his hand, and the car is lost. You know that, and he knows it as well. And he mocks your anxiety and your helplessness: 'You will not dare to touch me!'

He is right. You will not dare to touch him ... for even if you might risk your own life, you are travelling with your mother, and you will not dare to endanger your life for fear she too might be killed. . .

So you will leave the steering-wheel in the hands of the chauffeur. Moreover, you will try not to hinder him—you will even help him with advice, warning and assistance. And you will be right, for this is what has to be done.

But how will you feel when you realise that your self-restraint might still be of no avail, and that even with your help the chauffeur will be unable to cope? How will you feel when your mother, having sensed the danger, begs you for help, and, misunderstanding your conduct, accuses you of inaction and indifference?

The secret police officer who called the attention of his superiors to this article wrote that it had been printed in a considerable number of copies and that the author had received numerous letters of congratulation for having published it. By means of such press articles the seething atmosphere of the Moscow congresses of September 1915 was communicated to wide circles of the newspaper-reading public in Russia, creating an atmosphere of crisis and increasing the sense of insecurity. The surprising-thing about this propaganda was that it did not call for action by the people, that it did not appeal to the population to make an effort to remove the 'mad chauffeur' and his government.

After September 1915 the Voluntary Organisations became a more important channel for the circulation of this seditious propaganda. Their work inevitably put them into close contact with the bureaucratic apparatus and with the military authorities. They ran a bush telegraph of news and rumours concerning the alleged machinations of a 'Black Bloc' which existed only in their imagination.

The Voluntary Organisations were in permanent conflict with the bureaucracy, which they were supposed to assist. The bureaucratic apparatus was doubtless obsolete, slow-moving, frequently overtaken by events, and to a certain extent corrupt in an old-fashioned way. On the other hand, the Voluntary Organisations were inexperienced in much of the work they had undertaken, undisciplined and anarchic in their methods and unorthodox in their accountancy: new forms of wartime corruption easily took root and spread in such Organisations.

It is difficult for the historian to discuss the pros and cons of the case of the Tsarist administration against the Voluntary Organisations. The important thing to note, however, is that on neither side was there any readiness to acknowledge fairly and frankly the efforts and achievements of the other. It was a war à outrance conducted by means of scurrilous mutual denunciation, in which the aggressive initiative certainly belonged to the leadership of the Voluntary. Organisations.

The self-advertisement of the Voluntary Organizations was completely unrestrained, and in fact survived the political downfall of their leaders. In emigration many of them collaborated in the publication by the Carnegie Foundation of a series of volumes vindicating their wartime activities with well-documented arguments.35

The mere fact that the Tsarist government was forced to tolerate these activities of groups and bodies openly hostile to it shows how irreplaceable they were in the national war effort, and yet the claims of these organisations to have saved the country from disaster, not only without the collaboration and support of the government but against its malevolent resistance, did not go unchallenged. On the one hand, the government itself hit back by publishing the figures of the enormous subsidies which the exchequer was paying to the Voluntary Organisations in order to make it possible for them to carry on with their work. On the other hand, even among those particularly susceptible to anti-government propaganda, and even more so among those already prone to a revolutionary mood, the feeling grew that there was much corruption involved in the work of the Voluntary Organisations. Rumours were circulated of enormous profits made by firms with whom the WICs had placed orders, and resentment against this new and particularly wicked form of war profiteering was growing. The Parkinsonian growth of the administrative apparatus of the Voluntary Organisations, who frequently duplicated each other's functions, resulted in more and more men claiming exemption from regular military service. The 'zemgussar'—(Zemstvo hussar) the smart Alec and dodger in pseudo-military attire—was satirised in the folklore of those days. The government held their fire in answering the attacks on them by the liberals, but it was clear that they were hoarding political ammunition for the moment when they could dispense with the help of the Voluntary Organisations and could at last bring them to account for the economic and political corruption of which they were widely suspected.

It is astonishing that under these circumstances the war effort Russia achieved so much in such a short time. The Year of 1916 saw a most spectacular recovery in the ammunition and arms supply, which, after the stabilization of the front in the winter of 1915-16, led in the summer of 1916 to the success of the so-called Brusilov offensive.

[End selection pg 181]

[The next few sections of the text detail the accelerating rumor and demoralization campaign conducted against the government by the Progressive Bloc and its allies in the military (who desired a Palace Coup to replace the Czar) which gradually transformed into direct public slander of Czarina Alexandra and a series of incoherent and increasingly fantastical allegations against Czarist officials or imperial court personalities, especially the folk healer Rasputin]

[Begin selection pg. 196]

7. THE ASSASSINATION OF RASPUTIN

The Milyukov broadside marked a new departure in the liberals' policy of extorting reforms from the Tsar. The accusations of treason, of preparations for a separate peace, and of support of the 'dark forces' by the Empress herself became generally accepted and were openly discussed not only by politicians but among the people at large and the army in particular. These beliefs created a kind of national unity which embraced the members of the grand-ducal families and the liberals alike. The rumours and accusations were not based on any facts, but their uniformity and all-pervasiveness seem to point to one single source sufficiently authoritative to have impressed both the highest strata of society and the liberal Duma circles.

In the subsequent search for this source the attention of those defending the memory of the murdered imperial family naturally focused on the politicians who spread these slanders. Thus S. S. Oldenburg, the cautious and accurate historian of the reign of Nicholas II, puts the blame squarely on Guchkov.36 And certainly Guchkov did his best to spread the rumour. This does not, however, prove that he was its originator: for this he lacked the necessary authority, especially since he was known to be a personal enemy of the Tsar and his consort. Less critical and well-informed commentators have assumed the existence of some well-organised conspiracy on masonic lines behind these rumours. We believe that an analysis of the circumstances preceding the murder of Rasputin may lead us to a clearer understanding. The initiator of the plot to assassinate Rasputin was the young Prince Felix Yusupov, the heir to the largest private fortune in Russia and the husband of a much-loved niece of the Emperor, Princess Irina, the daughter of his sister, the Grand Duchess Xenia. Yusupov himself has given an account of his motives and the dramatic circumstances which led him to become a murderer.37 According to him, he had closely followed the November debates in the Duma, where the accusation of high treason was made in more or less open terms, and had been particularly impressed by the speech of the right-wing deputy Purishkevich, who, following the Milyukov attack, had denounced the existing regime as a tool in the hands of 'dark forces'. Yusupov was then living alone in Petrograd (his wife and child were with his parents in the Crimea), training at an aristocratic cadet school in order to get a commission and go to the front. Young Yusupov's social contacts had no limits. There was almost no house in Russia, no personality whom he could not approach directly without introduction. He was particularly intimate with the family of Rodzyanko, whose wife was the closest friend of his mother, Princess Zinaida Yusupov.