You should really read this introduction to the Russian Revolution (Part 4)

Russian Revolution: Quadrilogy

I had only planned on doing one more of these introductions to the Russian Revolution, but I simply ran out of room. There are just too many topics to cover, even in this relatively small slice of history. I decided to expand the first half of the final article into an article of its own. As always, this is not intended to be a comprehensive (or strictly chronological) retelling of events. Rather, I want to introduce you to a larger frame narrative, along with key people, places, and concepts, that will enhance your understanding of any more specific material when you read it.

This series was written for people without any background knowledge at all. However, it does presume that you’ve read all the articles that have come before this. If you haven’t yet, please do so now or else this article won’t make any sense to you.

Part 1: The February and October Revolutions

Part 2: Post-Revolution Russian politics/The aftermath of the October Revolution

Part 3: National and ethnic divisions within the Russian Empire/The Ice March

I’m going to repeat some things just to refresh your memory. It’s tough even for me to juggle all these events. The way I see learning history is drawing an overlapping circle over and over again. You’ll keep drawing outside the lines a little bit (adding more and more context) but eventually the result will be a much thicker boarder. This stuff is more than just trivia. You’ll get a better understanding of whatever you’re interested in if it’s accompanied by knowledge of other pieces and how everything fits together.

Finally, please upgrade to a paid subscription right now. I don’t even have space to do this at the bottom of the essay. More than 20,000 people have read this series so far. If just a tiny fraction of them upgraded, I wouldn’t have to ask. Please help me. These really do make a big difference in my life.

And now to the essay:

By mid-1918, the Revolution was in dire straits.

Although Bolshevik Party Chairman Vladimir Lenin had successfully overthrown the weak Russian Provisional Government just months earlier in the October Revolution, serious threats to the new Soviet regime were emerging from all corners.

The first major setback for the Bolsheviks came in Finland. Finland had declared its independence from Russia shortly after the October Revolution. Although the Bolsheviks had formally recognized Finland’s independence soon after, this was merely a ploy to avoid a premature conflict with Finland’s conservative government.

The Bolsheviks organized labor unrest in Finland’s major cities. Strikes, sabotage, and work stoppages threatened to topple the already fragile Finnish economy (seriously disrupted by the chaos that had overtaken Russia, its biggest trading partner). Political street violence became commonplace and it seemed clear to everyone that a larger Bolshevik uprising would follow soon. The White Guard, a conservative militia that at first acted as law enforcement (the old Russian Imperial police had dissolved following the February Revolution, leading to months of anarchy), was hastily assembled.

Finland’s conservative government appointed Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim to lead the counterrevolution. Mannerheim had spent most of his life as a cavalry officer in the Russian military, including time as an explorer and diplomat. Although Finns were exempt from conscription by Russia owing to Finland’s status as a Grand Duchy, they could volunteer for service with Russian forces.

When the local Bolshevik uprising finally arrived in January 1918, the Reds quickly captured most major cities in Finland and assembled an army that greatly outnumbered the White Guard. However, the Whites had the benefit of a pre-planned structure to resist the revolution. Mannerheim had been given supreme executive authority by mutual agreement of all Finland’s conservative factions.

This unified command greatly benefitted the Whites during the Finnish Civil War, allowing them to avoid the infighting and indecision that paralyzed other counterrevolutionary movements. The Finnish Whites successfully resisted the initial offensive from the Finnish Reds, who were openly supported with weapons and troops by the Russian Bolsheviks. Although the Reds had a larger and better-equipped force, they suffered from poor training and leadership.

By March 1918 the Finnish Whites had introduced conscription, allowing them to achieve numerical parity with the Reds, and launched a major counterattack. After a decisive victory at the bloody Battle of Tampere, Mannerheim had planned to march on Helsinki, the nation’s capital. However, Mannerheim’s plans were complicated by a large German military intervention on the side of the Finnish Whites.

Against Mannerheim’s orders, members of the Finnish government requested that the German Army send troops to recapture Helsinki, which had been seized by the Reds during their initial uprising. Although Mannerheim wasn’t hostile to Germany, he understood that open German military intervention could undermine the Whites’ claims that they were the true representatives of the will of the Finnish people. Although the Bolsheviks were internationalists and accepted help from other nations freely, they always accused their enemies of being mere puppets of foreign powers.

Furthermore, it was also obvious to nearly everyone that Germany was going to lose World War I at that point. Taking on Germany (which led the Central Powers in the conflict) as a partner could create serious complications for Finland when dealing with the sure-to-be victorious Allies after the war.

Over Mannerheim’s objections, the newly-invited German troops staged successful landings at Helsinki and several other cities along the Baltic Sea, sending the Finnish Reds into a panicked retreat. Mannerheim’s army pursued the retreating Reds and destroyed their largest remaining military formation at the Battle of Viipuri. The Finnish Civil War was effectively over in May 1918.

Bolshevik atrocities in Russia were well known by that point and there was great hatred of the Finnish Reds for the months of chaos that had preceded their uprising at behest of Bolshevik Russia. The aftermath of virtually every major battle of the Finnish Civil War was marked by mass executions of Red prisoners by the Whites. Tens of thousands of Red prisoners of war were also herded into prison camps with very poor conditions, where thousands died from disease or starvation.

Although the Finnish Reds committed many atrocities of their own during the war, the Finnish White Terror, as these killings would become known, would often be cited among justifications for the Red Terror, the official Bolshevik policy of political repression and mass execution adopted later that year.

The victory of the Finnish Whites also triggered the first major Allied intervention into the Russian civil conflict. The strategically important port of Murmansk in the Arctic Circle, near the Finnish border, was home to massive stockpiles of Allied war material from the time of Russia's participation in World War I. The Allies did not formally recognize the Bolshevik government, and a tense standoff emerged between the Bolsheviks and the nearby British North Russian Squadron, who refused to allow the Bolsheviks to access these supplies.

The apparent pro-German orientation of the victorious Finns (who regularly raided Bolshevik territory after the Finnish Civil War) alarmed the Allies, who were concerned that the Bolsheviks would fall too quickly and be replaced by a pro-German Russian government. Lenin, seeing that the tiny local Red Army force could not hope to resist the Finns, invited the Allies to occupy Murmansk. In March 1918 several thousand British and American troops entered the city, easily driving off the Finns with little fighting.

The Bolsheviks quickly soured on the Allied presence, but the Allies simply refused to leave—citing their obligations to their (now deposed) former partner the Russian Provisional Government. Lenin, already concerned about the prospect of a German invasion, could not risk entering into a direct conflict with the Allies and was forced to hold his tongue.

In Ukraine, the situation for the Bolsheviks had become even more grim. Although the nationalist Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) government had been pushed out of the capital Kiev by the Bolsheviks (owing to an ill-advised decision by the UPR to betray the pro-Russian military officers whom they had allied with to suppress an earlier Bolsheviks uprising), the UPR had signed an agreement with the advancing German Army: The Germans would guarantee the independence of Ukraine (in practice, to militarily occupy the entire country) in exchange for very generous allotments of grain to be shipped from Ukraine to Germany.

The Germans easily overcame the local Bolsheviks and took control of most strategic points in the country. Lenin, terrified by the recently-revealed weakness of his Red Army (which had suffering a seemingly-unending string of devastating defeats both in and outside of Russia), encouraged Ukrainians not to resist the German occupiers out of fear that renewed fighting might provoke the Germans to advance into Russia proper and topple the Bolshevik government once and for all.

The UPR was dominated by socialists of various kinds. Its main focus before the Revolution had been land policy.

Russia (of which Ukraine had been a formal part for centuries) had a special class of peasants called serfs who were tied to the land that they worked, controlled by the state or noblemen. Although Czar Alexander II had abolished serfdom in 1861, the state land that had been worked by serfs wasn't given to the serfs to be owned in individual plots. Instead, it was distributed to village communes.

These communes offered none of the incentives of private ownership and distribution of land, surplus, and other essentials of agricultural life was often very unfair. Serfs who had belonged to noblemen (a more common arrangement in Ukraine) were in an equally unfavorable position, often forced into exploitive sharecropping or tenant farmer agreements by large landowners.

The land situation left nearly everyone unsatisfied. For decades, violent radical movements had able to get widespread public support by proposing any changes at all to this system.

Once nominally back in power (Ukraine outside of German occupation remained in a state of anarchy), the UPR adopted a strangely radical position: banning private land ownership and announcing impending mass farm collectivization. These were policies that the Bolsheviks had been pushing for all along.

This move alarmed the Germans, who understood (from previous disastrous experiments with farm collectivization) that such a change would quickly prove unpopular and threaten the supply of grain to Germany. Senior officials in the UPR were also implicated in a bizarre plot that included the kidnapping of the German Army’s main banker in Ukraine. These missteps led to the total loss of Germany’s confidence in the UPR’s ability to govern as a client state.

The Germans found a solution to their problem in the form of Pavlo Skoropadsky, a respected former Russian military officer. Although Skoropadsky had been born in Germany and served in a series of prestigious positions in the Russian government (even becoming the personal military advisor to Czar Nicholas), he was descended from a long line of Ukrainian statesmen.

After a short popular revolution (backed by German troops) against the UPR in Kiev, Skoropadsky was declared Hetman (literally “head man,” a traditional Ukrainian Cossack title equivalent to Ataman among Russian Cossacks) of all Ukraine. Skoropadsky’s new Ukrainian Hetmanate was a German puppet regime. Skoropadsky had no illusions about his role: He was a military dictator given unlimited leeway by the Germans so long as Ukrainian grain shipments flowed to Germany on time.

Although the Hetmanate was never widely-popular owing to its brazen connections with the German occupiers, stability did return to the country after nearly a year of chaos. Skoropadsky made some efforts to appease Ukrainian nationalists, changing signs and government publications from Russian to Ukrainian (although Skoropadsky could not even speak Ukrainian).

Skoropadsky also brought many Russian monarchists and conservative officers into the Ukrainian government, professionalizing the military. One of his biggest recruiting successes was securing the loyalty of Count Fyodor Arturovich Keller, Russia’s greatest cavalry commander and the mentor of future Russian Civil War hero Pyotr Wrangel. Count Keller agreed to lead the Ukrainian military.

Skoropadsky was another “breakaway” figure during this time period who had no real plans for long-term independence from Russia. He had earlier pledged to reenter Ukraine into a federation with Russia once the Bolsheviks were removed. It’s likely that his embrace of Ukrainian nationalism was motivated just by a desire to get a better deal from whatever future Russian successor government emerged to return Ukraine back into the fold. Few expected the Bolshevik regime to last very long, and no one believed that Skoropadsky-led Ukraine could survive without German troops.

The Ukrainian puppet regime under Skoropadsky managed to force the Bolsheviks (increasingly desperate) into a peace agreement. In the countryside, nationalist troops under the nominal command of UPR military chief Symon Petliura (who was jailed briefly by Skoropadsky, but released in a show good-faith that was not returned) continued their brutal campaign against non-ethnic Ukrainians, killing tens of thousands of civilians, while also launching guerrilla attacks on the German Army.

In the western regions of Ukraine, the crimes against civilians took on an apocalyptic character as the anarchist Black Army of Nestor Maknho waged a war of extermination against Dutch Mennonites, pacifist ethnic Germans who had been invited to settle the region by Russian monarch Catherine the Great hundreds of years earlier.

The atrocities against ethnic Germans in Ukraine and surrounding nations became so infamous that it spurred the creation of the Freikorps (“Free Corps” or “Volunteer Corps”). Although the Freikorps began as self-defense militias for German farmers in many areas of Eastern Europe (often targeted for violence by surrounding, mostly Slavic, majority populations), after the end of World War I these groups were joined by thousands of veteran soldiers and became involved in filibustering expeditions in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (which had large German minority populations).

Far from Germany, the Freikorps became accused of the same crimes against civilians that these groups had nominally been formed to prevent. Other Freikorps detachments (these were independent paramilitary units with no central command) would also play a major role as anti-communist fighters in both the post-WWI German Civil War and the turmoil of the Weimar Republic that followed.

The Bolsheviks encountered perhaps their biggest setback yet in the Revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion. The pre-Revolution Russian Empire had significant populations of Czechs and Slovaks. Many had been forced to flee to Russia over their opposition to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which controlled Czechoslovakia. When Russia entered World War I against the Central Powers, of which the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a part, Czechs and Slovaks in Russian territory petitioned Czar Nicholas II for a national military unit of their own.

The understanding with the Allies was that, after the Austro-Hungarians were defeated in WWI, Czechoslovakia would finally be granted its independence. Although the unit would nominally be under the political control of the Czechoslovak National Council (a government in exile recognized by the Allies), in practice it was to operate as though it was just another part of the Russian Army.

Even after the Czar was overthrown in the February Revolution, the Czechoslovak Legion proved to be an effective fighting force. It one of the few units to make serious gains during the otherwise-disastrous Kerensky Offensive. The Legion’s ranks were bolstered with Czechoslovak Austria-Hungarian prisoners of war taken by the Russians. Volunteering for the Legion was almost guaranteed to offer a much nicer experience than life in a remote POW camp, outside the dangers of combat.

After the October Revolution, the Czechoslovak Legion was one of the only units attached to the Russian Army that remained relatively intact. Most Russian divisions were plagued by the assassination of officers and mass desertion, but the Czechoslovak Legion was free of those problems. It was a homogenous all-volunteer force, morale remained high despite the political turmoil. They proved far more resistant to Bolshevik agitation because only a small number of Legionnaires could even speak Russian. There was also simply nowhere for the Czechoslovaks to desert too. The men had joined the war to free their country from the Central Powers, who had only ended up taking even more territory on the Eastern Front.

As a large military force (more than 50,000 men) in the middle of a collapsing foreign empire, the Czechoslovak Legion was in a precarious position. This position became more precarious after the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which removed Russia from World War I. The presence of the pro-Allies Czechoslovak Legion became a major diplomatic liability for the Bolsheviks, who were constantly concerned that the Germans might invade.

Furthermore, the Red Army was still weak and desperately needed trained and disciplined men. Virtually no Russian officers or senior enlisted men were willing to fight for the Reds, and those who were were largely rejects and incompetents from the old military. Bolshevik military head Leon Trotsky hoped to recruit the Czechoslovak Legion into his forces, as he had successfully done with the Latvian Riflemen.

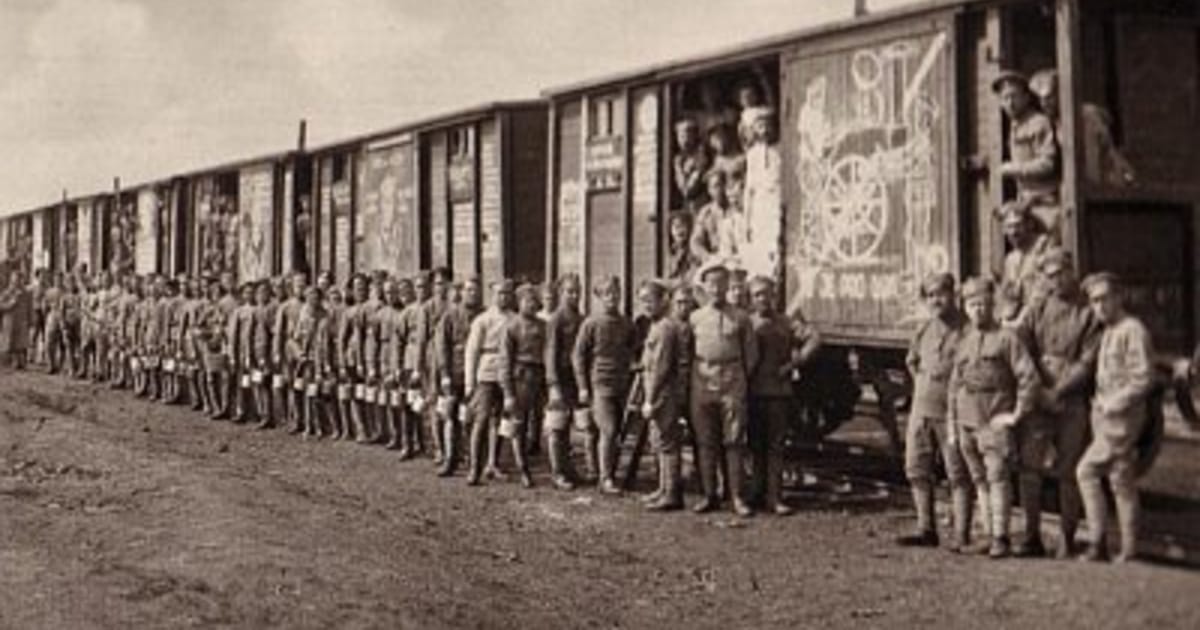

The Czechoslovak Legion negotiated an agreement with the Bolsheviks for railroad transportation across Siberia to the critical Pacific port of Vladivostok, where they would be evacuated by the Allies.

Siberia, the vast largely-undeveloped eastern part of Russia, had been captured by the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution. However, the relatively low population density of the region (with accompanying small Bolshevik garrisons) along with its dependence on the singular Trans-Siberian Railway, Siberia’s only major transit corridor, made Bolshevik control of Siberia more far fragile than it was in European Russia.

Organizing rail traffic along the Trans-Siberian Railway was complicated even in the best of times and the years of political and economic chaos that overtook Russia had thrown the entire system into disarray. Although the Czechoslovak Legion had made an agreement with the Bolsheviks, months after the deal the Legionnaires were still scattered across Siberia, stranded by delays and shortages of all kinds.

In many places along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, the stranded Legionnaires outnumbered the local Bolshevik garrisons. The Czechoslovaks also had superior training and organization owing the Bolsheviks’ blanket hostility towards (and frequent murders of) officers from the old Imperial Army.

In May 1918 there was a major altercation in the city of Chelyabinsk between the Legionnaires and Hungarian POWs, who were being transported west to German lines by the Bolsheviks (accelerated return of prisoners was one of the major conditions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk). The POWs viewed the Legionnaires (many of whom had once served in the Austro-Hungarian Army) as traitors. Greater bloodshed was only avoided by the intervention of the Bolsheviks, who arrested some of the Czechoslovaks. The remaining Legionnaires seized the entire town from the Bolsheviks in order to free their comrades.

After this incident, Trotsky made the rash decision to publicly order the disarming of the entire Czechoslovak Legion. Although the Legion had already surrendered their heavy weapons as part of their deal with the Bolsheviks, the agreement allowed them to keep their small arms for personal protection. This effectively meant that, for the Bolsheviks, there were suddenly tens of thousands of enemy infantrymen spread across nearly every strategic point along the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The Legionnaires refused to be disarmed and instead drove out the tiny local Bolshevik garrisons, eventually capturing nearly the entire span of the railway east of the Ural Mountains.

Conservative Russian officers and recently-ousted Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, who had been in hiding up to that point, used the opportunity to stage simultaneous uprisings of their own. These Russians quickly set up several different local anti-Bolshevik governments and joined forces with Czechoslovak detachments across the region.

Nearly all of Siberia (most strategically important cities were concentrated along the Trans-Siberian Railway) would fall to the enemies of the Bolsheviks in just a few weeks. Significantly, a combined White Russian and Czechoslovak force would capture the Imperial gold reserves, which had been sent to Siberia for safekeeping after World War I began.

The Allies had been watching developments in Russia over the last few months with a mixture of horror and excitement. Although Great Britain, France, and Japan had been allied with Russia in World War I, they also viewed it as a geopolitical rival. These powers hoped to carve up, or at least extract major concessions from, Russia during this moment of weakness. British agents had played a large role in organizing the February Revolution and had extensive contacts within Russian leftwing anti-Bolshevik circles.

America had more humanitarian motivations for its intervention in Russia owing to President Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic foreign policy goals. The State Department’s position regarding Russia was always incoherent at best. The American Red Cross, a neutral charitable organization, also began massive aid to millions of Russian civilians who had been cut off from food, winter clothing, medical care by collapse of Russian society. Although Lenin was hostile to these interlopers, the Bolsheviks had proven themselves to be totally incapable of (and uninterested in) providing basic necessities to the civilians in their territory. It was only American-organized relief that kept hundreds of thousands of people alive during these desperate years,

Most American Red Cross employees (among whom were many foreigners) were unsympathetic to the Bolsheviks owing to their systemic mistreatment of civilians and frequent atrocities. However, Raymond Robins, head of the American Red Cross Mission in Russia, was a far-left labor activist very close to Bolshevik leadership. Robins was suspected of informing for the Bolsheviks (potentially spurring the arrest of rival Red Cross employees) and redirecting critical supplies exclusively to Bolshevik-controlled areas.

After the Russian Civil War Robins wrote a report on conditions in Bolshevik Russia that was widely condemned for sanitizing the failures of the new regime. He also unsuccessfully tried for a decade to gain diplomatic recognition for the Bolsheviks from the United States.

Speaking through the Czechoslovak National Council, the Allies ordered the Czechoslovak Legion to stay put and support the local anti-Bolshevik forces after their initial uprising. Having suddenly stumbled into effective control of nearly half of Russia, Allied command hoped that it might use this card to reopen the Eastern Front against Germany.

Unbeknownst to all but a few, the greatest success of the counterrevolutionaries so far meant tragedy for Czar Nicholas and the other members of the Imperial family.

After the February Revolution, the Provisional Government had arrested Czar Nicholas and his family without charges, imprisoning them in a series of remote locations across Siberia to prevent rescue attempts by loyal officers. Offers of asylum from foreign countries evaporated and it soon became clear that the Imperial family would never be allowed to leave.

Treatment of the Imperial family dramatically worsened after the October Revolution. The poorly-organized and -disciplined Bolshevik guards regularly robbed and menaced their prisoners. Eventually, the captives were relocated to a fortified compound in the city of Yekaterinburg.

Although the Bolsheviks had been planning the murder of the Czar and his family for some weeks beforehand, the mutiny of the Czechoslovak Legion and subsequent uprisings from conservative Russian officers sent the Bolsheviks into a panic. They began executions of their high-level prisoners out of fear that those prisoners might be used as figureheads for the resurgent counterrevolutionary movement if they were ever rescued.

Grand Duke Michael, the Czar’s younger brother and successor (who had himself been imprisoned without charges after surrendering power to the Provisional Government) was shot in mid-June 1918. All the killings occurred in secret. The various members of the Imperial family had not had contact with each other or the outside world for months.

On July 17, 1918, Czar Nicholas, his family, the family doctor, and several servants (who had refused to leave out of loyalty) were herded into a basement by their guards and brutally shot to death with handguns. Their bodies were crudely disfigured to prevent identification and hidden in a mineshaft before being reburied in a more remote location. The remaining members of the Imperial family in Bolshevik custody at other locations would be executed the following day.

The murder of the Imperial family was kept a carefully concealed secret by the Bolsheviks out of fear that the atrocity might encourage revolts or trigger a diplomatic crisis (Czar Nicholas was a cousin of both British King George V and German Kaiser Wilhelm II). Even after the murder of the Imperial family was officially acknowledged by the Bolsheviks in 1926, they falsely claimed that Lenin’s government had been uninvolved and that the killings were the act of rogue local officials. In reality, Lenin had personally given the order.

After months of disaster, by July 1918 the Bolsheviks had reached their lowest point yet. However, more than two years of fighting still remained in the Russian Civil War. While the Bolsheviks remained a unified (albeit shaken) force, their multiplying enemies had multiplying (and often mutually-exclusive) goals. As the fissures between the various White Armies grew deeper, the Red Army would slowly begin to solve the almost-fatal problems that had plagued it since its inception.

But that is another story.

I’ve written a follow-up to this essay that covers the various anti-Bolshevik plots that emerged from leftist groups within the Bolshevik heartland in the months that followed, culminating in the nearly successful assassination of Lenin. You can read Part 5 of this series here.

It’s fascinating how history plays out so frequently in the 20th Century with the traditionalist elements outnumbered and outgunned but better trained and disciplined than their socialist/Communists counterparts. It speaks to their respective mentalities and visions of life: independent excellence or mediocre masses. To borrow from StarCraft, it is a battle between the Protoss noble, standing for glory even if alone, while the Zergs seek to form a blob covering the entire Earth with the sheer weight of their mediocrity. Look at Rhodesia Bush Wars, Finnish Civil War, Russian War between the Whites and the Reds. Ultimately, if the smaller number of traditionalists can make a decisive victory early on like in Finland, then they can intimidate the greater numbers. However, if it drags on, then the sheer weight of numbers, lower morale and outside forces resupplying the socialists will win over like Rhodesia.

Or contemporarily, compare the Seattle strike and riots that were immediately dealt with by Mayor Ole Hanson who mobilized his forces quickly like you mentioned before and the Summer of Floyd that continued seemingly indefinitely because it was not stopped quickly (but then faded away after Kenosha). This historical imbalance between numbers/weapons of the Right and the Left has made the US such a challenge for these revolutionary types. The traditionalists in America are the ones armed to the teeth and can’t be wiped out as they have been elsewhere.

The story of the Czechoslovak legion is one of the more unique stories in military history, thanks for bringing attention to it. May deserve a post of its own. A great example of how the tide of war can be almost instantly reversed through political miscalculation (In this case, of Trotsky and the Reds)