You should really read this introduction to the Russian Revolution (Part 2)

Russian Revolution: The Squeakquel

I decided to write a sequel to my introduction to the Russian Revolution. I think it’s really important for people to have at least a basic background narrative that they can use to frame their thinking when they learn about historical events. Oftentimes it seems like people will learn about an event, but be unable to put it into context. They don’t know how it connects to other incidents (if they know about those incidents at all) or other relevant people, trends, and places that could shed greater light on whatever they’re interested in. New facts should be more than trivia.

This total lack of context can end up turning something that’s kind of true into a very misleading picture. People become unable to assess relative importance or become fixated on some details while totally ignoring others. They lack the mental models to understand what happened in the past and what’s happening today. Eventually, they end up in dumber places than if they were just oblivious to everything.

It’s important to emphasize that this can happen even if the person is smart and doesn’t have any bad intent. People just don’t know the history these days. Schools don’t teach them. They won’t be exposed to it through the media (or, if they are, the media version of history will be so inaccurate you end up knowing less than nothing). Their teachers and parents and friends won’t know either. They just don’t know.

My hope with this series is to provide more context to help people understand one of my main areas of interest: the Russian Civil War (1917-1921). Please note: I’m not trying to write a comprehensive history or include every important aspect of the period. There are lots of important topics that I don’t have space to talk about or, if I did talk about them, they would end up being more of a distraction than anything else.

I’m also going to play around with timeline a little bit just for the sake of readability. For instance, the escape of Kornilov and Alexeiev into Cossack territory actually happened before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed, even though I mention the escape after the treaty. With so much going on near-simultaneously, it’s difficult to adhere to a strict chronology and maintain any kind of narrative coherence. I’ll try to bring things up roughly as they occur, but that gets more and more difficult when you’re trying to explain certain events (which may unfold over the course of several months) in detail. For me, readability is king. I want you to finish the article.

My goal here is to create an accessible narrative that anyone coming in off the street can understand without much background knowledge. Once you have that narrative, then you can add to that base in any number of different ways. This essay does presume that you’ve read my original introduction to the Russian Revolution. If you haven’t read that yet, do so now or what follows isn’t going to make a lot of sense.

One final note, please upgrade to a paid subscription right now. These essays take a very long time to research and write. If just 10% of the people who read the first essay in this series upgraded to a paid subscription when they passed by this message, I’d never have to ask again.

Please, person reading this, upgrade to a paid subscription right now. It’s only $5 and makes a very big difference in my life. I am sincerely grateful for all paid subscribers.

And now to the essay:

The Bolshevik Party’s coup in Russia’s capital Petrograd (today known as St. Petersburg) on October 25, 1917, widely known as the October Revolution, was a huge success for the revolutionaries. Although Provisional Government Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky had escaped the city and connected with military units still loyal to his government, this small force fell apart as soon as it encountered serious resistance from the Bolsheviks. Military leaders were unwilling to send Kerensky reinforcements or assist him in any way following the Kornilov Affair, and, with no remaining allies, Kerensky fled the country.

Petrograd fell under control of the Bolsheviks, who proclaimed the fall of the Provisional Government and the creation of a new Soviet Republic in Russia. Fighting between the Bolsheviks and loyalist troops continued for several weeks in Moscow, though in most parts of the country there was no fighting at all. Everyone was just waiting to see what would happen next. Bolshevik delegations arrived in many cities and claimed control, although they had no legal authority and the political situation was murky at best. Many areas refused to recognize these delegations and even drove them out with force. The Bolshevik base of support did not extend far outside major cities and a few radicalized military bases.

Now is a good time to describe Russian politics after the February Revolution that toppled Russia’s monarch, Czar Nicholas II. The February Revolution brought together Russian leftists and some Russian rightwingers to create the Provisional Government. However, the Provisional Government was just intended to act as a caretaker until elections could be held for the Constituent Assembly, a parliament that would rewrite Russia’s constitution and create a permanent democratic republic. Although Kerensky had formally proclaimed the creation of the Russian Republic (without the required elections) shortly before he was deposed, this had little impact on the situation.

Absolute monarchists (a significant minority of Russia’s population at the time of the February Revolution) who favored a return to the old Czarist system were excluded from the Provisional Government. The major Russian parties vying for positions in the Provisional Government and proposed-Constituent Assembly were:

The Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs) - Democratic socialists who had existed as a political party for several decades (mostly outside of government). Their base of support was the rural peasantry and their main goal was redistributing public and private land to the peasants. The SRs were discredited in the eyes of more conservative-minded Russians because of the party’s brutal and widespread terrorist campaign following the unsuccessful 1905 Revolution (I’ll probably do a write-up of this at some point). Despite their radical agenda, the SRs opposed further revolutionary changes to the Provisional Government and (though there was some internal disagreement) opposed Russia’s exit from WWI. This was the largest and most popular party after the February Revolution, with support generally around 40% of the population.

The Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) - Liberal “reform” party that supported a number of progressive policies from the eventual implementation of a constitutional monarchy to universal suffrage and the protection of civil liberties. The party was created by radical nobles but moderated over time to appeal to the educated classes more generally. It favored stability. As this was the only non-socialist political party allowed in government after the February Revolution, many conservatives who would otherwise have been unrepresented joined its ranks. The Kadets were ardent Russian nationalists and opposed Russia’s exit from WWI. This was the second most popular party and the party that exercised the most control over the Provisional Government. Support for the Kadets typically hovered near 30% of the population, including broader rightwing coalition that formed around it.

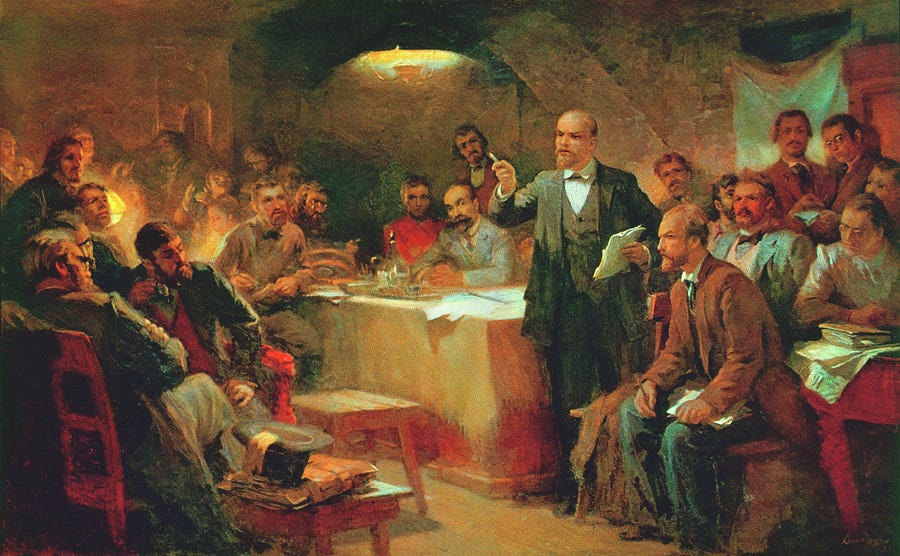

The Bolsheviks - A radical communist party that advocated for the abolition of national and class barriers, along with an end to private property. Its leadership openly supported armed violence in order to fuel revolutionary change. Their base of support came from urban workers and soldiers. Although the party was relatively unpopular before WWI, the Bolsheviks received massive (secret) funding from Germany, allowing them to substantially expand their payrolls and propaganda operations. Naturally, the Bolsheviks favored Russia’s withdrawal from WWI (enhancing their popularity among many people who didn’t buy into their economic agenda). They exercised disproportionate control over the Soviets, public workers councils that issued decrees with authority that competed with that of the Provisional Government. Support for the Bolsheviks typically ranged between 10% and 20% of the population, depending on whatever the prevailing political winds were.

The Mensheviks - A party that split from the Bolsheviks when both were created in 1903. They had largely the same platform as the Bolsheviks, though the Mensheviks favored peaceful activism rather than revolutionary violence to achieve their goals. Their support was always smaller than that of the Bolsheviks, and a large minority of their members defected to the Bolsheviks after the February Revolution over the Menshevik support for the continuation of WWI. Despite their diminished national significance following the defection, they maintained significant local majorities in Transcaucasia and Georgia.

The Left Socialist Revolutionaries (Left SRs) - A faction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party that eventually became its own separate entity after the October Revolution. This party sprang out of the SRs’s (much more radical) local organization in Petrograd. It had mostly the same agenda as the main party, though it differed from them in advocating for the overthrow of the Provisional Government and transfer of all power to the Soviets. The Left SRs typically aligned with the Bolsheviks, though they opposed any exit from WWI, albeit for internationalist reasons rather than the typical nationalist ones (the Left SRs didn’t want to make peace with Germany, an imperialist power).

The Bolshevik coup in Petrograd in October 1917 was condemned by every other major party as an illegal seizure of power.

Although Bolshevik-aligned forces nominally controlled Petrograd, a state of absolute confusion prevailed. There had been little actual fighting, most participants in the revolution were not part of any larger conspiracy but rather merely going along with the mob. The stunning Bolshevik success had mainly resulted from very few people being willing to risk their lives to defend Kerensky’s disastrous government.

The first serious opposition to the Bolsheviks emerged from the Junkers. Junkers were military school cadets, typically teenagers, training to become officers. Junker schools existed in many major cities across Russia, and were almost always hotbeds of conservative sentiment. The Junkers hadn’t been deployed to the front lines yet and were spared the demoralizing conditions that members of the Russian military had suffered under for years. Furthermore, as visible representatives of Russia’s military traditions, they were frequently targets of abuse from urban workers, deserting soldiers, and liberal activists, hardening the Junkers’ anti-revolutionary stance.

Although the Junkers were mostly teenagers, they had weapons, training, uniforms, and military organization. This made them a fearsome force in a city dominated by largely disorganized mobs. Several days after the Bolshevik coup, on October 27th, they launched the Junker Mutiny with support from Committee for the Salvation of the Homeland and the Revolution, a short-lived alliance between the Kadets, SRs, Mensheviks, and various other local political entities.

Cadets from several different Junker schools advanced on strategic points around Petrograd simultaneously. They seized the all-important Petrograd telephone exchange, cutting off communications too and from the city. They also captured Bolshevik strongholds like the Hotel Astoria and even disabled the power at the Smolny Institute, the headquarters for the entire Bolshevik Party.

Despite the Junkers’ remarkable success, anti-Bolshevik political groups were unwilling to provide them with anything other than moral support. No mass rising accompanied these gains and the teenagers soon learned that most of the adults who had urged them forward were not willing to actually stick their necks out to do anything about the Bolsheviks.

The Bolsheviks counterattacked with a large number of Red Guards, ideologically-motivated paramilitary units, and drove the Junkers into the Vladimir Military School. After suffering heavy casualties in an attempt to storm the building, the Bolsheviks wheeled artillery pieces into the city and bombarded the school into rubble. Hundreds were killed on both sides, though the Bolsheviks retained control of Petrograd and a growing number of urban areas.

One revealing consequence of the Junker Mutiny was the fall of the Constitutional Democratic Party, also known as the Kadets. Although the Constitutional Democratic Party’s leadership could be tied to the Junker Mutiny through its support of the Committee for the Salvation of the Homeland and the Revolution (which in practice provided virtually no help to the Junkers), the biggest problem for the party came from its name.

The “Kadet” nickname originated from the abbreviation of the party’s name in Russian: Konstitutsionno-Demokraticheskaya partiya. “K-D” sounds like “cadet” in Russian. The Kadets weren’t military cadets or anything like that, it was just a play on words. However, most Russians of the time were illiterate. Only 37% of men and 17% of women over the age of 7 could read. When news went out that military cadets had risen up to protect the hated Kerensky government, many people (not unreasonably) believed that it was actually the Kadet Party leading the counterrevolution.

This confusion was ruthlessly exploited by the Bolsheviks, who tried at every turn to associate the liberal Kadets with the far more conservative (and unpopular) military cadets. Support for the Kadet Party dropped substantially as many supporters and local officials began to fear reprisal for the Kadets’ supposed role in the failed uprising.

One defining feature of the Bolsheviks was a total disregard for the truth in all interactions with everyone else. The Bolshevik’s platform for Russia could be (and was) anything that would make the Bolsheviks popular at the moment and harm the Bolsheviks’ rivals. There was no regard for consistency. They would lie about everything, all the time. For instance, although the Bolsheviks called for the abolition of private land ownership entirely, they publicly adopted the Socialist Revolutionaries’ more popular land policy (which would distribute land to peasants in private plots). They had no intention of implementing this policy, they just knew it was popular and that publicly adopting it would undercut the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Having successfully ended the military threat to their new regime from both Kerensky and the Junkers, the Bolsheviks set about consolidating their power politically. Although the SRs and Mensheviks had competed with the Bolsheviks for control of the Soviets before the October Revolution, after the revolution they were almost entirely excluded from them (both parties had walked out in protest at a critical vote in the influential Petrograd Soviet upon learning of the planned Bolshevik uprising).

At that point, nearly everyone regarded the Bolshevik coup as illegitimate even if they weren’t willing to risk civil war to oppose it. However, the people most likely to actually resist the Bolsheviks takeover, conservative military officers, were still spread across thousands of miles of Russia’s frontline in World War I. Although the situation before the October Revolution had been bad for Russia’s military, after the revolution it entered into a state of freefall collapse.

Assassinations of officers became an epidemic. In Kronstadt, headquarters of the Russian Baltic Fleet, the Bolsheviks received overwhelming support. Thousands of officers were executed by their men merely for being officers. Similar atrocities occurred all over the front. Baltic sailors (also called Kronstadt sailors) became infamous throughout the revolution and its aftermath for their brutality. These men formed the military backbone of the early Bolshevik regime and were used to terrorize the civilian population.

Another pillar of early Bolshevik military power were the Latvian Riflemen. Latvia1 was controlled by the Russian Empire at the start of World War I. The Russian military often raised national units for convenience’s sake. However, the dramatic failures of Russia on the Eastern Front after the February Revolution had led to Latvia’s conquest by Germany. The Latvian Riflemen had a string of bad Russian senior officers, which contributed to the radicalization and alienation of the men. As Russia began a process of political collapse, the Latvians (despite having little affinity for Bolshevism as an ideology) threw their lot with the Bolsheviks. As one of the few intact and well-disciplined military units still operating in what was turning into an apocalyptic situation in the interior of Russia, the Latvian Riflemen became the elite enforcers of the Bolsheviks’ will.

Tens of thousands of government bureaucrats and other employees in critical sectors like banking and transportation (including railroad union members) refused to cooperate with the Bolsheviks as they attempted to wield the machinery of the Russian state. They went on strike and obstructed access important documents and material. Significantly, employees of the state bank refused to allow the Bolsheviks to access Russia’s state funds, creating a financial crisis for the Bolsheviks.

In the backdrop of this fairly widespread resistance, the Bolsheviks agreed to hold elections for the long-awaited Constituent Assembly on November 25, 1917, when they had originally been scheduled by the Provisional Government.

The November elections produced results that were less than desirable for Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin. Although the Bolsheviks made a respectable showing, gathering nearly 24% of the vote, greater public support than they had ever obtained before, they came in a decisive second to the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which gathered 40% of the vote (and nearly 50% if you include the Socialist Revolutionary Party’s Ukrainian offshoot). The Bolsheviks simply had limited popularity outside of their urban strongholds and radicalized military units.

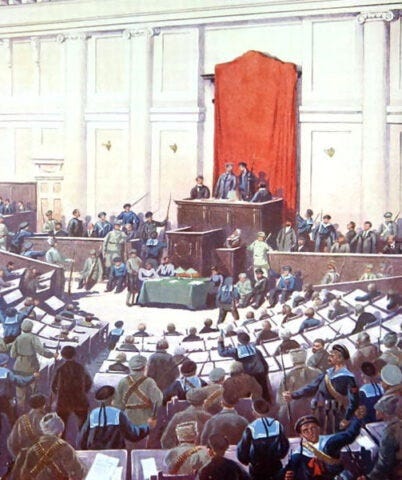

The Constituent Assembly, Russia’s first truly democratically-elected parliment and the product of centuries of struggle by Russian radicals, was allowed to meet for approximately 13 hours on January 18, 1918 before the Bolsheviks ordered it dissolved. All power was henceforth transferred to the Soviets, which were carefully controlled by Bolshevik Central Committee. The Bolsheviks formed a dubious coalition government with the Left SRs (who had received about 1% of the vote) and several rogue Mensheviks (around 3% of the vote) and began firing into the crowds that had assembled to support the Constituent Assembly.

It became clear to virtually everyone that the Bolsheviks had created a one-party dictatorship for themselves. Strikebreaking became the new priority for the Bolshevik government. In order to deal with internal threats, Lenin ordered the creation of the Cheka, a new Bolshevik secret police organization. Rogue government workers were threatened and even had their families held hostage by the Cheka in order to guarantee their compliance. Although the death penalty had formally been banned by the Bolsheviks upon their taking power, executions became commonplace.

A massive robbery campaign began as the Bolsheviks nationalized the holdings (including personal deposits from private citizens) of all major banks. These stolen goods were to be smuggled out of the country and sold overseas at greatly reduced prices in order to fund Bolshevik activities abroad (no foreign powers would allow the Bolsheviks to access Russia’s foreign reserves). Common criminals were released from prison en masse and often recruited by the Bolsheviks to the Red Guards. Law and order totally broke down in Bolshevik-controlled areas.

As Russia entered its darkest political period yet, the German Army was once again advancing nearly unopposed across Russian-controlled territory. Lenin was desperate to end the war quickly in order to allow the Bolsheviks to concentrate on their internal enemies. On March 3, 1918, Lenin agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, led by Germany.

The terms of the treaty were humiliating. The Bolsheviks agreed to surrender Russian control of Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and several provinces in the Caucuses. The territory lost accounted for roughly 34% of the former Russian empire's population, 54% of its industrial land, 89% of its coalfields, and 26% of its railways. The Bolsheviks also agreed to pay significant “war reparations” to Germany, mostly in the form of state gold reserves that the Bolsheviks had managed to gain access to and private property looted during their nationalization of the banks. The Left SRs formally broke with the Bolsheviks in protest over the agreement, claiming that the Bolsheviks were little better than German agents (which, although this was not publicly known at the time, they were).

However humiliating these concessions may have been, Lenin was happy to be out of the war as enemies within Russia closed in on him from all sides. Also entering into the Bolsheviks’ calculus was that, even as Germany was triumphant on the Eastern Front, on the Western Front its situation had become untenable with the entry of America into the war on the side of the Allies. It seemed unlikely that any agreement the Bolsheviks made with the current German government would last for very long. Furthermore, with the Russian military in a state of collapse, at that point the Bolsheviks could not have exercised control over the areas they gave away even if they had wanted to.

As the Bolsheviks stood on unsteady ground at the start of 1918, in the south of Russia the most serious organized opposition to the Bolshevik was coming into being. General Lavr Kornilov, the widely-respected former head of the Russian military, had escaped2 from Bykhov Fortress, where he had been confined since the Kornilov Affair, along with other major Russian military figures like General Anton Denikin. These officers headed into Cossack territory near the Don and Kuban rivers, where local authorities had refused to surrender power to the Bolsheviks.

Further contributing to the efforts of the early counterrevolutionaries was General Mikhail Alexeiev, another former head of the Russian military, who had gone into hiding after the October Revolution and built a secret network known as the Alexeiv Organization to smuggle military cadets (who were being hunted by the Bolsheviks after the Junker Mutiny), volunteers, weapons, and critical war material towards South Russia with the hopes that a proper army could be formed to fight the Reds, a name the Bolsheviks had taken for themselves.

To contrast themselves with the Reds, the burgeoning anti-Bolshevik coalition was collectively dubbed the White Movement. Although politically schizophrenic (bringing monarchists, republicans, liberals, and moderate socialists under a single banner) the Whites were united in their opposition to the Bolshevik dictatorship and desire for the renewal of Russia after years of disaster.

After 4 months of chaos following the October Revolution, Russia was on the edge of a full-blown civil war. Soldiers who had spent years on the frontlines of World War I prepared for an even greater struggle that would determine the fate of their nation.

But that is another story.

I’ve written a follow-up to this essay that provides background on the various national and ethnic tensions within the former Russian Empire, as well as describes the start of the counterrevolution in South Russia. You can read Part 3 of this series here.

If you enjoyed this essay, please upgrade to a paid subscription right now. I am asking you, the person reading this right now, to do this. You’ll also get access to all the podcast episodes available on this Substack. Please upgrade to paid right now.

Latvians are often referred to as “Letts” and Latvian is referred to as “Lettish” in literature from this period. Latvia was previously known as “Lettonia,” a somewhat strange Latinization (changing the Cyrillic characters used by Slavic languages into Latin characters used by Romance languages without regard for phonetics) of the country’s name developed by Henry of Livonia, a renowned historian and missionary, in the 13th Century.

The story of the “escape” of General Kornilov and other future leaders of resistance to Bolshevism is very interesting and almost entirely unknown. As was often the case during this period, Kornilov was imprisoned by soldiers who sympathized with him. This imprisonment likely spared him and the other prisoners execution at the hands of the Red Guards or other Bolshevized soldiers at the start of the October Revolution. The fate of these men was in limbo after Kerensky fled. The final Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Russian military was General Nikolay Nikolayevich Dukhonin, a relatively minor figure with few allies who had been elevated to such a high role only because of his good relationship with (and political dependence on) Kerensky. Despite his very vulnerable position following the October Revolution, Dukhonin personally confronted Lenin in a meeting, refusing to cooperate with him or accede to his demands concerning the military. Lenin ordered Dukhonin’s dismissal immediately following the meeting. However, before news of his removal became widely known, Dukhonin, in his last official act, ordered that the prisoners at Bykhov Fortress be released. Dukhonin knew that issuing such an order was signing his own death warrant, but took no steps to flee or bargain for his life. He was arrested by the Bolsheviks, who attempted to countermand his order releasing the prisoners, but by then it was too late. The men had escaped and would go on to create the White Army, the most serious threat ever posed to Bolshevik power. Dukhonin was publicly stabbed and beaten to death by an mob of Bolshevik sailors as he was being transported through a rail station. They stripped the body naked and shot it to pieces, refusing to allow it to be buried. The story of the killing became widely known, an infamous example of Bolshevik savagery.

A great read for an area of history most have little knowledge of at best. Especially the Junkers attempt at dealing with the chaos

"They would lie about everything, all the time." Sounds familiar.